Alex Cox: Iconoclast

By Tristan Patterson

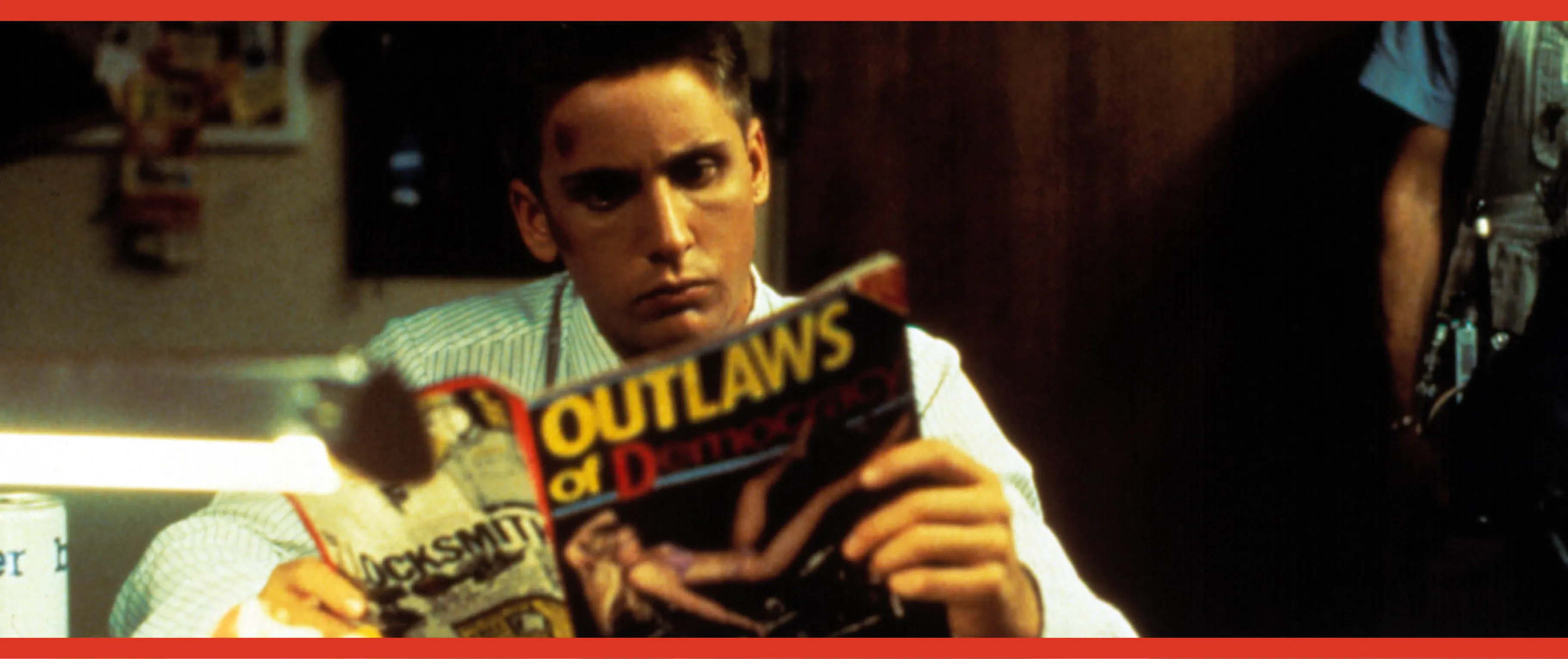

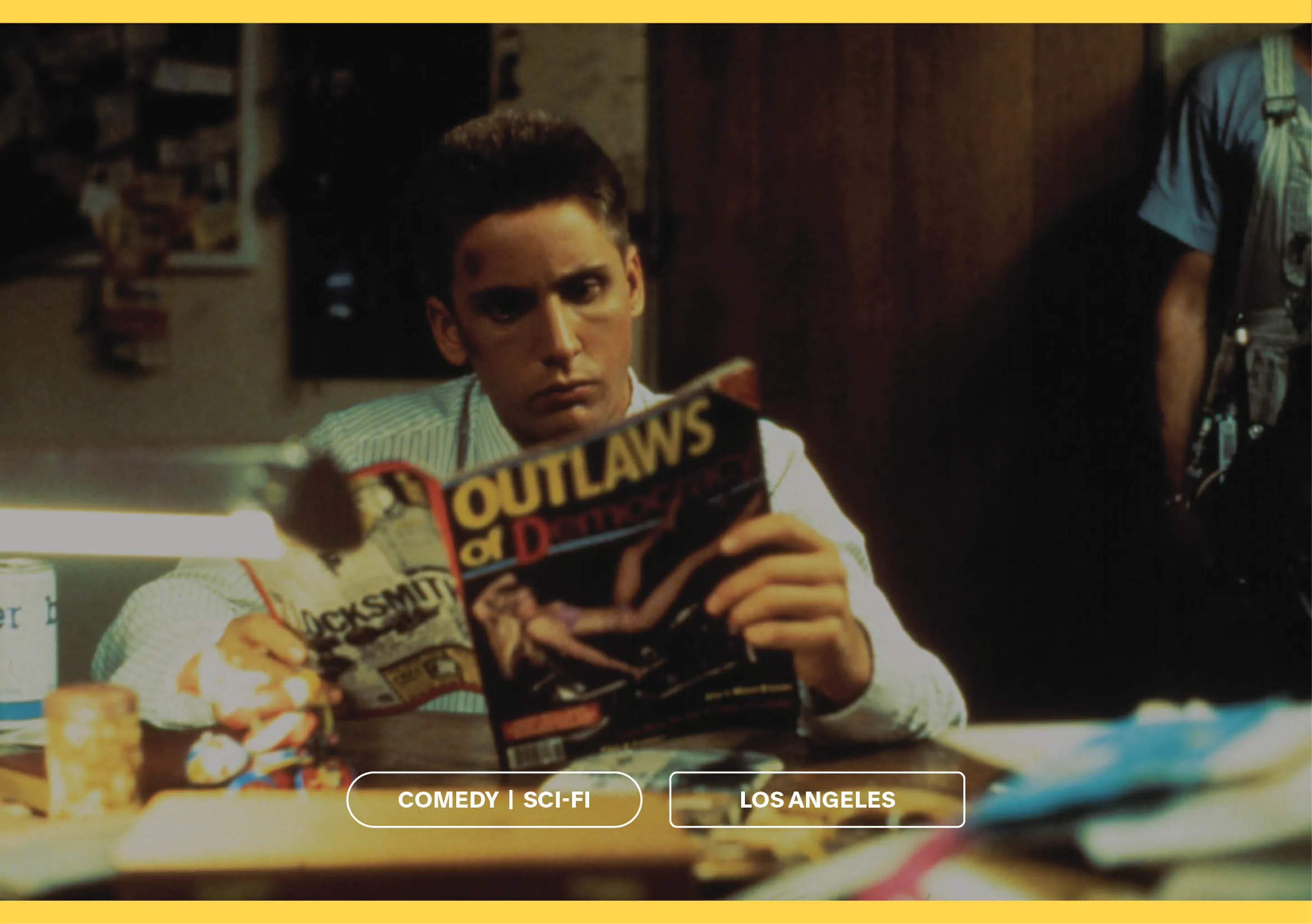

Repo Man, dir. Alex Cox, 1984

Alex Cox: Iconoclast

The Repo Man director and subversive punk auteur on the origins of his alternate vision of Los Angeles

By Tristan Patterson

April 12, 2024

In the pantheon of cult movies about the city of Los Angeles, Alex Cox’s Repo Man is an army of one. A strange brew of ’80s punk rock and negligent car payments set against a backdrop of looming nuclear annihilation, the film tells the story of Otto, a young rebel without a clue (or a car) who falls in with a crew of repo men hell-bent on locating a missing Chevy Malibu. With characters named after cheap domestic beers and a cosmic subplot laced with apocalyptic dread (the Malibu has mysterious, radioactive cargo stashed in its trunk that vaporizes all who come in contact with it), the film is both a gonzo celebration of working-class desperados and a deadpan satire of the paranoid frontier they inhabit. Released in 1984 by Universal Pictures with a theme song by Iggy Pop, Repo Man would ultimately find its target audience on VHS, capturing the minds of stoned teenagers in living rooms across the nation ready to call bullshit on the Reagan era.

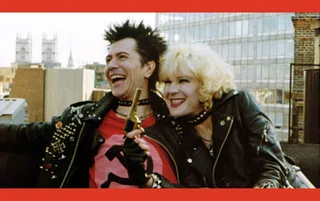

Alex Cox during the production of Sid and Nancy, 1986

The film also announced the arrival of a provocative new voice in independent cinema, one more than willing to defy the exhausted conventions of Hollywood in pursuit of more original visions. In a career that has spanned four decades, Cox has rarely repeated himself, embracing new forms of experimentation at every turn. A starter menu of his work includes the rock and roll biopic Sid and Nancy (1986); the revisionist spaghetti Western Straight to Hell (1987); and the historical epic Walker (1987), a Herzogian account of American imperialism and megalomania in Nicaragua. That Walker was made with the support and collaboration of the Sandinistas, Nicaragua’s revolutionary left-wing government at war with the Reagan- and CIA-backed contras during the time of the film’s production, tells you everything you need to know about where Cox was coming from.

Before he went astral, however, Cox was a 23-year-old expat from Liverpool, studying film at UCLA on a Fulbright scholarship. There he embarked on a filmmaking odyssey through late-70s Los Angeles that would culminate in Edge City (aka Sleep Is for Sissies), his $8,000, 40-minute thesis project. The portrait of a young and broke British illustrator (played by Cox) drifting through a trippy New Hollywood scene juxtaposes vérité documentary footage with science fiction–genre elements—equal parts Mike Davis and William Burroughs. In this sense the film’s title functions as both a reframing of Los Angeles and an articulation of the mind-state that living in the city can produce. Cox would soon stake an even more permanent claim to Edge City in Repo Man, identifying it as the conceptual metropolis (and stand-in for Los Angeles) where the film is set.

As he prepares his return to Edge City for a Repo Man sequel, Cox spoke with Galerie from his home in Yachats, Oregon, a coastal enclave that derives its name from a mix of native words meaning “where the trail leaves the beach.”

From left: Killer of Sheep, dir. Charles Burnett, 1978; Emilio Estevez and Olivia Barash in Repo Man

In your book X Films: True Confessions of a Radical Filmmaker, you write that you arrived at UCLA film school from England in the late 1970s “knowing nothing about the place, or the city it was in.” How did you imagine Los Angeles might be? And how did it compare to the city you encountered?

I hadn’t really had an expectation of Los Angeles, because my notion of the United States wasn’t specific enough. I knew there was a United States and it was a very big place. It had mountains and deserts and flat areas and New York and cities on the coast and big cactus and Monument Valley! So I didn’t really have any thoughts about Los Angeles. But I remember, having gotten there and seeing what the situation was like, how people got around. I realized I needed transport, so I got a motorcycle. That was the most important part of my arrival in Los Angeles: having transportation.

Were there films you’d seen that informed your sense of place?

I’d seen Point Blank and I’d seen Kiss Me Deadly and I’d seen the one with Norma Desmond [Sunset Boulevard]. I’d seen films that sort of overtly took place in Los Angeles, but most films didn’t. Most films seemed to take place in a vague America whose actual location was less apparent.

Was your ambition to become a grand auteur of cinema? Or were you thinking, This will be something interesting to do with my life for a couple of years?

I wouldn’t say grand auteur was ever in the cards, you know? [Laughs] What do you mean, be like [Jean] Renoir or something? I was just a very happy-go-lucky English film student with a motorcycle. There may have been people at UCLA who thought they wanted to be Renoir, but most people there wanted to be independent filmmakers in the style of the 1970s, in the style of Dennis Hopper when he made Easy Rider or Monte Hellman. There were certain directors, American directors, working in Los Angeles we admired—Charles Burnett, who made Killer of Sheep. They were all directors working for relatively low budgets in the independent sphere. That was what we wanted to do. That was the nature of that school. I don’t know why or how people gravitated there or if they had any notion of that going in. Partially, I suppose, it’s because it was cheaper, because if you were to have gone to the industry school, the Hollywood school, which was USC, you would have paid a lot more money in fees.

It seems like there was something in the air at UCLA at that time, a belief that it was possible to make a feature film that pursued an idiosyncratic or deeply personal vision.

I think that’s right. Ever since then we’ve been fighting against everything becoming so predictable. So I think it was a very good time. There were people making features because Charles had made Killer of Sheep. It showed what the possibilities might be in terms of visuals, locations, acting, storytelling. We were in awe of Charles Burnett and aspired to be like him. Jamaa Fanaka had made Penitentiary as a student feature. But you still had to have the funding and the persistence to make it through the 80- or 90-minute mark. [But] that was the wonderful thing about the school: It was the most interracial, international environment that I’ve ever been in.

Edge City (aka Sleep Is for Sissies), dir. Alex Cox, 1980

At UCLA you began work on a project that would ultimately become Edge City. As an outsider, were you searching for your own language to capture and make sense of this strange world you found yourself in?

Well, probably, yeah. I think you make films about what you like and what interests you. If you look at a film by Lindsay Anderson and say, “Why are various things in that film?” [it’s] because he was interested in them at that time. And maybe later he would even cease to be interested in them. But when he made If.… and when he made O Lucky Man! and when he made The Old Crowd, he was very specifically concerned about something and wanted to say something.

The film opens with a fish-eye shot looking down on L.A.’s deliriously confusing freeway system. Over this, we hear blasts of cultural detritus from a car radio. Where did these recordings come from? Did you find them or did they find you?

Most were things I think I did record off the radio. And then there were other things, warnings about what to do when the nuclear missiles were on their way, that I got off records. They must have had them on records at school in the sound effects library. I mean, the radio was playing all day long. You could just turn it on at any time—you know, just turn on the tape recorder and record some stuff and then go play with it.

You were interested in experimenting with material that was found.

Yeah, and I think that’s inevitable in a certain sense with a low-budget film like the films that we so admired. They all made do with what was there. They didn’t get to build the environment. They had to embrace the environment they were in and find interesting stuff in it.

This kind of found material creates an effect for the viewer of being an alien trying to discern what makes the city tick through these strange clues. This mirrors the experience Edge City’s protagonist is having. Was that inspired by your own life at the time?

Most of the things that I did in that film and in Repo Man were things that had happened to me or things that people had said to me. You know, people [in L.A.] would tell you these stories, and even if they weren’t true, they were so interesting. I enjoyed those kinds of things, and then when making a film, I would tend to exploit them. So some crazy thing that some guy told me ends up in the screenplay. Especially if you’re not from around there, people sometimes open up and tell you a great deal of stuff because they think they won’t ever see you again. Also because a lot of people aren’t from there—they’ve come from somewhere else, so everyone is somewhat adrift.

There’s a throughline from Edge City to Repo Man where the characters you write have these insanely quotable monologues or deadpan exchanges of dialogue that lead to some pretty off-the-wall epiphanies.

Again, that’s tied into the films of the ’70s where even though they could often be totally fantastical and heroic, there was something that was genuine and authentic about them as well.

In Edge City these scripted elements collide with vérité documentary footage shot on the streets of L.A. This injection of reality amplifies the dread and unease we feel about what’s happening in the city. Is this another example of how low-budget films find creative ways of embracing found environments?

I was probably led into that by Michael Miner, who was the cinematographer, because he so enjoyed going down into L.A. and shooting black-and-white footage on the streets. He was a terribly good cinematographer. Very, very interesting and inspired. He later became a writer—well, he was always a writer, but he later wrote the script for RoboCop. He had such an eye: “Right around this corner is something interesting I think you’ll like.” So the experience of making the film with him was that kind of process of discovery. Empty freeways in the Valley, you know.

Harry Dean Stanton in Repo Man

It’s almost too good to be true that you would go on to make Repo Man and Michael Miner would go on to write RoboCop, both films that repurpose genre to serve more personal artistic and political concerns. Is that something that you guys talked about even then?

Oh, we talked about everything. We just talked nonstop—about films, because we had so many references in common and things that each of us didn’t know and that each one of us could turn the other one onto. That was very exciting. We were very polyglot. We were enjoying the New German Cinema. We were enjoying Kurosawa movies and Buñuel.

In Edge City there’s a piece of documentary footage—a glimpse of Nicaraguan demonstrators marching through L.A. in 1979—that feels prescient to the political concerns of your later work. You’ve said the revolution in Nicaragua was not being covered by the mainstream press. I’m struck by the idea that by going out with a camera, you located a deeper truth about the city than the pop-culture flotsam you were hearing on its airwaves.

That’s the amazing thing about Los Angeles: It’s somebody else’s world, isn’t it? It’s the city of Our Lady of the Angels from Spain, from the desert of the Indios. It’s only comparatively recently that the white guys came and took it over and brought the “benefits” of petroleum. Los Angeles is very, very culturally interesting in that way. To see a demonstration in downtown L.A. about the revolution in Nicaragua—supporting the revolution against the dictator Somoza? Wow, that’s really exciting. Why don’t we hear more about that kind of stuff? It’s very eye-opening.

Were you already political, or was this the birth of a new political awakening?

I come from Liverpool, so naturally I’m against the royal family, I’m against the government in London, I’m against the BBC. You know, I have proper Liverpudlian politics and opinions, so I didn’t trust the Man, I didn’t trust the capitalists, I didn’t trust the government anyway. And perhaps the cynical, anti-London framework that I’d embedded as a child was beneficial in making me keener to investigate things.

How did you arrive at the title Edge City?

It was Michael Miner’s idea. Interestingly though, Frederik Pohl, the science fiction writer, wrote a story called “Growing Up in Edge City” around the same time. It was sort of a dystopian-future thing with kids as the protagonists.

As the protagonist of Edge City spirals into a drug-induced madness, life in Los Angeles begins to resemble the stuff of science fiction. You were starting to unlock a new way of depicting the place.

I just think it’s inevitable. I like science fiction. I read a lot of science fiction, so yeah, it was gonna get in, it was gonna creep in there. We were on the cusp of Reagan and Thatcher. Until then it had never seemed like a nuclear war was about to burst into fruition.

Were you also starting to think about what you’d do with your life when you went from being a film-school student to a graduate who needed to get a job? Did making the film illuminate a kind of work you wanted to pursue?

[Laughs] I mean, it was too weird to really do that in a certain way, but it did demonstrate that I could work with actors and that I could put together a narrative of some kind.

I worked in the UCLA film archive, preserving films. One day Ray Manzarek from the Doors called up and asked if we still had a copy of his student film. And I was a bit cheeky—I laughed and I said: “Are you kidding? We’ve already lost Jim Morrison’s student film. Surely we’ve lost yours.” I don’t know if he found that very funny, but I had a lot of respect for him, of course. Also, then, because he was the producer of [the L.A. punk band] X.

“…I didn’t trust the Man, I didn’t trust the capitalists, I didn’t trust the government anyway.”

How did punk influence the way you were thinking about film? Or how was it informing your thinking in general?

I went to a lot of punk shows with my colleagues from UCLA. Saw the local bands like Fear and X and Circle Jerks and enjoyed the whole thing immensely. And many great bands came from afar to entertain us too. The energy and the humor and the anti-corporate spirit were very encouraging.

Around this time, through an actor in Edge City, you met one of his roommates who—

Who was a repo man! Yes!

There’s a parallel here to the way you and Michael Miner went out into the streets of L.A. with a camera for Edge City and the way a crew of repo men took you into a new kind of “found” environment you might otherwise not have seen.

Definitely. It was the continuation of my voyage of discovery in Los Angeles. Without a doubt.

In Repo Man, Harry Dean Stanton’s character, Bud, is prone to passionate monologues about the codes of the job. Did the real-life repo men have any kind of moral compass?

[Laughs] Not really, no. They might have said, “Don’t fuck up the car,” but they weren’t romantics.

Did your experience hanging out with them change your understanding of the city?

It all seemed to be pretty much part and parcel with itself. Los Angeles seemed to be a certain way, and the longer we spent in it, the more it confirmed itself.

Around this time the L.A. punk scene was exploding and you moved to Venice. What was your life like there?

That motorcycle [I had in film school] broke. I had to get another motorcycle. There was this guy, Varnum Honey was his name. He was my motorcycle mechanic. He was totally into English motorcycles, so I ended up getting this Norton. It was a beautiful motorcycle, but it never ran. You just had to look at it, you know? So that motorcycle had to sit chained to the railing outside [my] apartment, and I had to get another motorcycle that would actually run. A lot of this was just about transportation. But [Varnum Honey] was an interesting character. He was the leader of a motorcycle gang. Many of those people I met in Venice told me a lot of funny stories that I used in Repo Man—and Varnum Honey had a Chevy Malibu.

The kernel of a big idea! You referenced Kiss Me Deadly as a film set in L.A. that you’d seen before you arrived. Something about Varnum Honey’s Chevy Malibu reminded you of this?

Kiss Me Deadly provided a structure for me. Because [what I’d been writing] was lacking in structure. The way that Kiss Me Deadly is structured, with the different times that they open the trunk of the car—or rather, that they open the box—I just replicated that, similarly, in the narrative [with the Chevy Malibu] to give it more of a skeleton.

The idea of something extraterrestrial being hidden in the trunk opens up the possibility of exploring thematic terrain that extends beyond a character study. Repo Man isn’t set in Los Angeles so much as a conceptual universe called Edge City.

My principal concern was nuclear war and the invention of the neutron bomb. And also punk rock. I was actually really concerned—I really thought we were going to get killed in a nuclear war. Still am! It’s stuff that’s necessary for people to contemplate. And people don’t contemplate it enough. People should watch Peter Watkins’s film The War Game every day for a year and meditate on what a nuclear war would actually be. They sit around and they don’t. So we find ourselves in a very weird, difficult position. I think that’s where I was coming from: I really wanted to make a film about nuclear war and the likelihood thereof. But that’s a very difficult thing to get going.

From left: Sid and Nancy, dir. Alex Cox, 1986; The War Game, dir. Peter Watkins, 1966

In Repo Man you create a protagonist in Otto, played by Emilio Estevez, who is very much a product of the L.A. punk scene. Were you thinking of Repo Man as a new kind of youth movie that someone like Roger Corman might finance?

I think everybody admired Roger Corman because he was the producer and director of independent films. He had discovered all these amazing talents, like Robert De Niro and Jack Nicholson. He’d given many, many people their early work. Francis Coppola. Everything about Roger was something that we all were full of respect for because he’d done such amazing things with low budgets. He had proved so creative and resilient that he was like an inspirational thing. At that time he was a very great inspiration.

The financing for Repo Man was ultimately arranged by Michael Nesmith, guitarist of the Monkees and heir to the Liquid Paper fortune. This feels like the kind of character the protagonist in Edge City might have encountered as he drifted through the New Hollywood scene.

Yeah, but that’s just what life is like. Life is full of odd stories and strange characters.

At some point someone says to you, “Pick any cinematographer in the world,” and you suggest Robby Müller, whose work with Wim Wenders on films like Kings of the Road and The American Friend personified the New German Cinema of the ’70s that you were watching with Michael Miner. Müller injects another outsider’s vision of L.A. into the creative process. What was your collaboration like?

Peter McCarthy, one of the producers, suggested we be very ambitious and pursue someone we really admired. That was Robby. He was just very, very good. He was one of the greatest cinematographers then living—very clear about what he wanted and what his aesthetic was. He was excellent on those levels. But he was very different as well from the DPs I’d known previously, who were very interested in camera movement and the potential of the camera. Robby was much more interested in finding a place to put the camera where it could film two actors simultaneously in a two-shot, and I think that was kind of genius on his part.

The city’s toxic sunsets have also never looked more beautiful. The experiences in L.A. that led you to make Repo Man call to mind a line of dialogue from one of the film’s characters, Miller, a working-class acidhead in the scrapyard who waxes poetic about the “lattice of coincidence that lays on top of everything” in Edge City.

The character of Miller [originally] wasn’t such an important character as he turned out to be. We had a different ending in which a neutron bomb, which was in the back of the [Chevy Malibu], exploded, killing everybody in L.A. Jonathan Wacks, who was one of the producers, and Martin Turner, who was the still photographer, suggested an alternate ending. It was the one in which Miller turns out to be the mystic genius, and he and Otto fly away in the car, which is really a time machine. I thought it was a very good ending. So then it became a question of trying to persuade Nesmith and the studio that we could change the ending at the eleventh hour. It was very difficult because the studio didn’t want to change the ending. Nesmith said, “Oh, just shoot the original ending, and then we’ll get some money and shoot another one later.” But we were too untrusting, and so we stuck with what we thought we should do and we shot the ending with Miller’s triumph.

Repo Man ends with Otto joining Miller in the Chevy Malibu. In a way, his cosmic journey through space, time and beyond mirrors your own post–Repo Man experience as you embarked on a filmmaking journey that took you to London and New York (Sid and Nancy), Spain (Straight to Hell) and Nicaragua (Walker). I’m wondering what’s become of this Edge City universe you discovered during your time in L.A.?

I think it would look pretty much the same, wouldn’t it? Why would it change? Why does anything need to change? The repo men are still sitting at their desks—they can take control of driverless cars and direct them to the repo yard or the sheriff’s office. Other than that, we’re about to go to nuclear war with Russia! Nothing has changed.