Chef's Fable

By Meghan McCarron

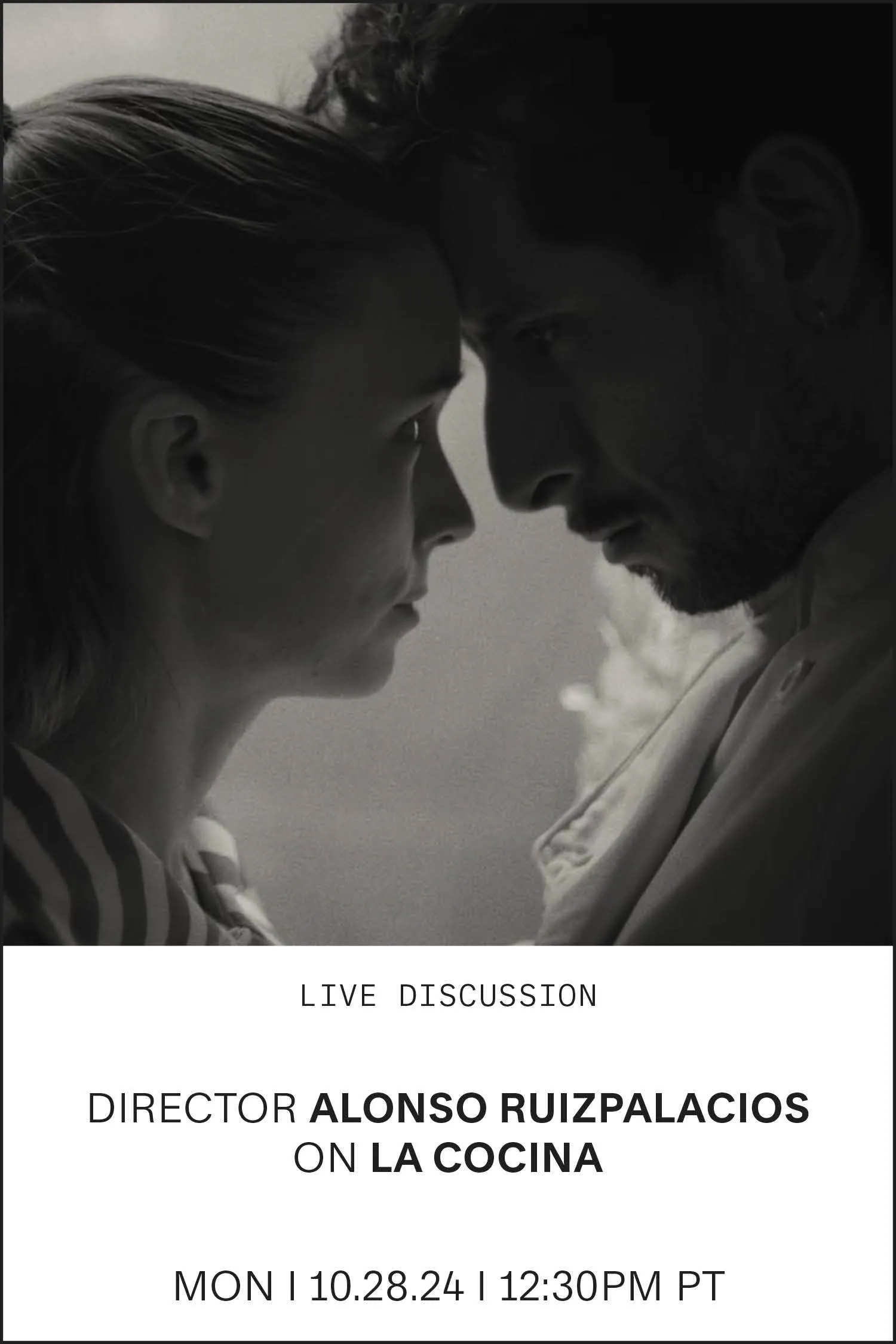

La Cocina, dir. Alonso Ruizpalacios, 2024

Chef’s Fable

Meghan McCarron

La Cocina director Alonso Ruizpalacios on kitchen sociology, the migrant experience and casting Rooney Mara

November 8, 2024

Alonso Ruizpalacios (courtesy of Grupo Expansión)

Over the past decade, cinema and prestige television have obsessed over restaurant culture. Chef’s Table enshrined the perfectly tweezered garnish, while works like The Menu and The Bear examined the darker side of high-end kitchens.

Director Alonso Ruizpalacios’s fourth feature film, La Cocina, is interested in a very different type of restaurant: a tourist trap in New York City’s Times Square. Shot in gritty yet timeless black and white, the film is a loose adaptation of the 1957 Arnold Wesker play The Kitchen. Featuring an ensemble cast that includes Rooney Mara, the film takes place over a single day of service slinging underdone pizzas and lobsters plucked from a tank. No one at The Grill is making art; this is a movie squarely about work.

As management chases down the culprit in a theft of $800, star-crossed lovers Julia, a pregnant waitress played by Mara, and Pedro, a cook played with wild intensity by Raúl Briones, struggle to decide their future, or at least find an escape from their present.

But these stories anchor a much broader fable about the tension between economic exploitation and the desire for connection and communication. The brutal machine of The Grill, where the ticket system sets a manic pace and many of the workers are undocumented, brings out the worst in everyone who works there, including Pedro and Julia, but it also drives them to find ways across barriers of language, gender and race.

A leading light of Mexico’s next generation of directors, Ruizpalacios has long mixed daring stylistic choices and complex social issues in his work. We spoke with him over Zoom about the real-world experiences that influenced this film, the politics underlying it and its uncanny moments of beauty.

La Cocina — the lobster tank

“Kitchens are very stratified societies. They’re very much about status and power.”

My understanding is that you worked for a time at a Rainforest Cafe in London, and that experience informed La Cocina a great deal. What positions did you work there? What did you expect going into that job, and what did you actually experience?

I worked there while I was studying acting in London many years ago, when I was in college. The Rainforest Cafe was in Piccadilly Circus, which is a lot like Times Square. It’s not the most peaceful place. It’s not a very nice place, in my opinion. But they gave good tips. I started working first inside the kitchen as a dishwasher, which is the lowest of the low.

Kitchens are very stratified societies. They’re very much about status and power. So anybody with a little bit of power will surely wave it around in front of whoever is below them. At the same time, it was a fascinating place. The people who work in kitchens are insane. They are adrenaline junkies. It’s also a place where people from different cultures are trying to make themselves understood in whatever way they can. It was fascinating to watch the flirting and the fighting. The Rainforest Cafe was full of drama. I quickly moved to waiting tables, and still I remember going to bed and having feverish dreams about being late with an order. But as I say, there are people that thrive in that.

Were there any specific aspects of your time there that showed up in this film?

A couple of people I met there ended up in spirit in the film. For example, the character of Samira, who’s played by Soundos Mosbah, is based on a French Algerian woman that I knew. She was the only woman in a kitchen full of men. They all respected her because she was super tough. But she was the only one who, when you were really in agony, would lend you a helping hand. She would be like, “Come on, Mexican, don’t cry, Mexican.”

The character of Pedro also has a lot of a guy I met there, the kind of guy who was tireless—you cannot wear them out. After the lunch rush, we’d all go and have a smoke and lie on the floor or in the street, wherever. And this guy would still be playing games and teasing people and picking fights.

![]()

Jeremy Allen White in The Bear

![]()

Ralph Fiennes in The Menu

Yours is the only movie I’ve seen that portrays a thing that happens in restaurant kitchens, where people are given a different name, often either a restaurant where they had worked previously or just their nationality. Can you talk about why you kept that detail in and how it ties into all these themes around language and immigration?

That’s what the film is about—this multinational experience, the migrant experience, which is the experience of the United States. It’s crazy to me the way we hear both candidates talk immigration now, as if it wasn’t a country that was made by immigrants, built by immigrants.

What I wanted to talk about in the film is how you get all these cultures trying to get along, but at the same time, the pressure makes people not be able to understand each other. It’s always the economic factors that fuck relationships up. It was very important to not have an idealized, Disney-fied version of that, but to see that racism doesn’t have a color. I’ve seen Mexican people be racist shits just as much as you can see a white person be a racist shit. And it’s a hard truth. Obviously, [discrimination or racism] is more common coming from the upper echelons of society. But it’s something Herman Melville called “the universal thump.” When somebody slaps somebody, that slap is going to get passed around. The film, and also the Wesker play, is very much about that.

What changed between staging that play and then many years later returning to it as a film?

When I staged it about 14 years ago, that was a first step in adapting the Wesker material. The play is set in postwar England and talks about another type of migration, the kind of phobia of Germans that there was in England at that time, for obvious reasons. The character of Pedro is German in the original play.

When I directed the play in Mexico, what was going to resonate more was the Mexican migration into the United States, because it’s a huge problem that we face. I’d already picked New York and Mexican immigration for the stage adaptation. When I got to do the film, it took me a long time to adapt into a script. I didn’t look back on the original play anymore. I adapted my own adaptation. So [La Cocina] is twice removed from Wesker.

Play adaptations can end up feeling stagy, but the movie is decidedly cinematic. The visual language is really rich. Did you have to consciously think about it as a piece of cinema to achieve that, or did that come very naturally?

It was a challenge that I knew I was giving myself: How do you make a play cinematic? That’s also why it took a long time to rewrite. It was a process of eliminating dialogue to carry action and meaning, and to make dialogue work on a secondary level. A lot of the time it’s just soundscape and what matters is what is happening underneath.

It was a lot of rewriting, and also keeping a pulse on it being a visual experience. There are a bunch of scenes where I took out all the dialogue and made it visual. When they come out of the lunch rush, there are very few words, and I needed that silence. In the play, and in my first version, there was a lot of talk about how [the lunch rush] was exhausting. But someone asking for a cigarette does all the talk. You don’t need to talk about their exhaustion.

From left: Raúl Briones and Rooney Mara in La Cocina

La Cocina was shot in black and white, and your first film was as well. In La Cocina, you also introduce a couple of surreal, expressive moments of color. Can you talk a bit about why you returned to black and white as a medium, and how you thought about those uses of color?

I love black and white more than anything. I would shoot every film in black and white if I could. It’s very pure to me, and very otherworldly. Of all the images we consume, it’s still a minor percentage. When I see an image in black and white, I look twice. It challenges me. It makes the viewer a participant in the image.

It’s very elastic. It can be documentary, and we can relate it to war images or historical pictures, or it can be very expressionistic and abstract. There’s something about black and white that lends itself more to framing things as a fable. I believe that there’s something about it that is also related to the subconscious in some weird way. The moments of color occur in the dream spaces of the characters. Julia’s letting Pedro into her world, which is the freezer. Before bringing him there, she says, “You don’t know me. You think you do, but you don’t.” And then it’s a little act of love that she brings him into the freezer.

Are there any parallels for you with the adrenaline of a kitchen and the adrenaline of shooting a film?

There are a lot of parallels between a film crew and the kitchen crew. Both take strong elements from the military. Escoffier, who was this French chef who created the brigade system in the late 19th century, took that obviously from the military and it helped him organize this chaos.

Film also has a lot of military elements in its organization that I think now is kind of changing. But traditionally, and certainly in Mexico, people used to have to say, “Yes, sir,” all the time. When I was writing the staff meal scene, when they’re all having lunch together before they open up service, I thought about staff meals with a crew, where hierarchy disappears temporarily and is suspended for half an hour and then we go back into it.

How did you work with the cast to prepare for shooting the film?

We had a period of four weeks of rehearsals, and we brought the cast down to Mexico and hired a theater space there. They would go in the mornings to cooking classes. [The actors] all learned how to cook the dish that their character cooks and got general kitchen skills to look believable. Others went to waitressing school and trained like that. In the afternoons we would improvise in this theater space in Mexico City. We would do lots of improv and theater games, so that the actors would have “flight hours” with their character and develop relationships with the other characters. The idea is that it’s a time to fail with freedom, and I think that provides the actors with firm ground for the shoot.

![]()

A Cop Movie, dir. Alonso Ruizpalacios, 2021

![]()

Museo, dir. Alonso Ruizpalacios, 2018

My understanding is most of the film was actually shot on a stage in Mexico. Were there any notable differences between this production and your previous ones?

It was a much bigger scale. I mean, my previous film to this one, A Cop Movie, was probably a tenth of the size of this film. And in every way, it was a very guerilla shoot. For [La Cocina] we built this incredible floatable set. We had actors coming from different parts of the world. So yes, it was a very different scale of a project. But shooting in Mexico also allowed us to play by our own rules. We were able to shoot for a longer period, so that meant that we could really take our time and try things.

And how did Rooney Mara come to be cast as Julia? Was there something in particular about her background as an actor that made you want to cast her in this role?

When I was rewriting the film I started thinking about Rooney. I remembered her performances from Carol and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and rewatched them. For this character, I needed somebody that is outwardly cold and hard, but inwardly emotional and in a very fragile state. Rooney can really portray that—she’s very good at subtext, and doing a lot with very economic means.

This idea of having a Hollywood star was important because I knew that we were going to have a Mexican actor who wasn’t a star. Pedro sees Julia as a Hollywood star. She’s just a working-class flesh-and-blood person. But that aura was useful for casting.

Raúl Briones delivers an intense, amazing performance as Pedro, like a number of actors in this film. He’s someone you’ve worked with previously. What made Raúl right for this role?

It was Raúl's ability to dive deeper with every take. That’s something that I knew from working with him [before]. He’s the most disciplined actor I know, and I needed somebody that I could trust fully.

I saw a lot of actors for this role. The only thing that kept me from thinking about Raúl originally was that he didn’t speak English, but from very early on he said, “If you give me this part, I will learn English.” And he learned English in just three months. That’s a testament to the discipline that he has. Plus, he had to fit as a character who never gets tired. And Raúl is like that. He has tremendous energy. His intensity, when he hits those dramatic, cathartic moments—that was the essential part of this character. I knew that Raúl could go into very dark places for those scenes.

“When somebody slaps somebody, that slap is going to get passed around.”

Why did you choose to set the film in New York? What about the city lends itself to this particular story?

The original play takes place in London, but that was too far for me. I wanted something that also gave me the chance to talk about my country, so bringing it to the U.S. made sense because of the very strong, intricate and complex relationships between Mexico and the United States, and because there is so much Mexican migration. At one point I did think about setting it in Los Angeles, but ultimately New York gave me that sense of timelessness. I wanted the film to start in a way that reminded us of those big migrations in the early 20th century, where you had all these boats coming into Ellis Island—this foundational American story. New York hits in a very particular, nostalgic way.

The contrast of the weather was the other factor that you don’t get in Los Angeles. The cold is something that people who migrate from these warmer countries are not used to or equipped to deal with. That’s another layer that adds to the huge challenge that migrating puts on them: It’s punishing, it’s unwelcoming, it’s isolating.