Miyazaki's Hidden Worlds

By Michael Leader

My Neighbor Totoro, dir. Hayao Miyazaki, 1988

Miyazaki’s Hidden Worlds

The lasting lesson of My Neighbor Totoro: Embrace childlike wonder

By Michael Leader

December 13, 2024

When I became a dad, I realized that I had slightly unrealistic expectations of life as a movie-loving parent—and for that I can thank Martin Scorsese. Back in 2011, Scorsese spoke on BBC Radio about the cinematic diet he had set for his then-12-year-old daughter, Francesca: classic Disney, golden-age Hollywood musicals and the silent comedies of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd—all projected from 35mm in their private screening room, of course. Children, Scorsese said, have no context, and therefore watch without prejudice. Francesca and her friends would sometimes ask ahead of a certain day’s screening if the characters talk in this one, or if their world is black and white or full of color. Ultimately, though, they were open to anything.

A trailer for My Neighbor Totoro

The memory of this program resurfaced several years later, when the time came for me to share Hayao Miyazaki’s My Neighbor Totoro with my son. The films of Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli inspire a deep connection. Miyazaki’s world and its landscapes, be they emotional, natural or fantastical, are adored by audiences young and old, and there’s no better place to find them than in the studio’s crowning achievement from 1988, an animated gem as simple, timeless and resonant as a fairy tale.

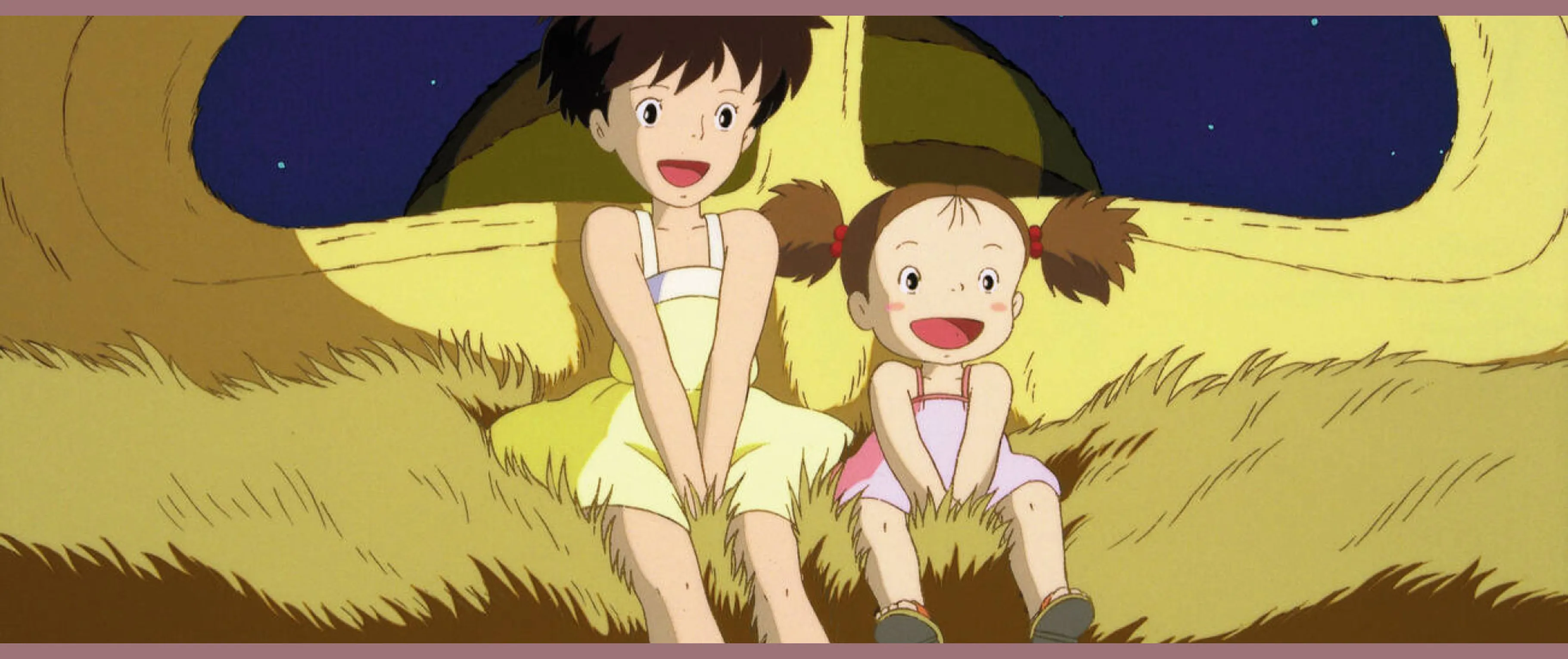

The movie tells of two young girls, Satsuki and Mei Kusakabe, who move to the countryside to be closer to their hospitalized mother, and their adventures with the creatures great and small that they find in the forests near their new home. Though the film had performed underwhelmingly upon release, over time it became a cult—and commercial—juggernaut, giving rise to an entire industry. Totoro the character, rather than the film, had always been a familiar figure in my son’s life. When he was born, friends and colleagues showered our household in Totoro paraphernalia: onesies, night-lights, plushies. One friend commissioned a bespoke artwork featuring a baby Totoro creature flanked by parent-size Totoros, which hung in the nursery. In more ways than one, we were already a Totoro family.

“My Neighbor Totoro is a guidebook for living life with eyes open to the magic of the mundane and the everyday.”

With the film itself, we had to take baby steps. For starters, the toddler was terrified of Totoro. You see, the creature has teeth! So when little Mei first meets the supposedly kindly forest troll and the film cuts to a perspective shot from inside its gargantuan mouth, looking out at the little girl sitting on his tummy…it was as if we’d subjected the boy to Jaws. Thankfully, that viewing was just the first of many. Much like the Kusakabes, we had moved from the big city to the country, within reach of ancient woodlands and closer than ever to Miyazaki’s natural idyll. But with each viewing, the film revealed itself to be as poignant a story about parenting as it is about reclaiming and celebrating childhood innocence.

I couldn’t help but find fellow feeling when Tatsuo—Satsuki and Mei’s university professor father—attempts to crack on with work with his four-year-old frolicking nearby, the action framed in such a way that the working parent is crammed to the side, with the child’s world of play overwhelming the shot. And then the borders are challenged by a furtive hand placing petals on the paper-strewn desk. “Dad, you be the flower shop, okay?”

It must be noted that Hayao Miyazaki was not a stay-at-home dad. For all the feminist messaging and aspirational female characters that can be found in his films, he was strictly old-school when it came to divvying up parental responsibilities. “I’m a father who works too hard and returns home late at night six days a week,” he wrote in a newspaper column in 1992. “That is why I have left family affairs and raising our children to my wife.”

The domestic, fantastical and pastoral tableaux of My Neighbor Totoro

Akemi Miyazaki—known professionally by her maiden name, Akemi Ōta—actually entered the animation profession a good handful of years before her husband. She received her first credit as an in-between animator on Toei Animation’s landmark all-color feature Hakuja den (Hajukaden: The White Snake Enchantress, 1958), the film that moved a teenage Miyazaki to tears and made him dedicate his life to animation. After the births of their two sons, Gorō and Keisuke, the couple initially attempted to balance work and childcare. But before long, Akemi’s career was sacrificed for her husband’s, which consequently flourished through the 1970s and culminated in his debut works as director, the adventure series Future Boy Conan (1978) and the swashbuckling caper Lupin III: The Castle of Cagliostro (1979).

Gorō, who in adulthood became the heir presumptive to the Ghibli kingdom after directing features such as Tales from Earthsea (2006) and From Up on Poppy Hill (2011), once wrote in a blog that he’d give Miyazaki senior “zero marks as a father, but full marks as a director.” It’s a distinction he clearly carries with him to this day. When I spoke with Gorō in early 2021, he told me that even in the thick of production, his highest priority is always to be back home in time for dinner with his young family.

In Hayao’s absence, Gorō had to turn to his father’s films in an attempt to understand him. Similarly, we too build an understanding of Hayao Miyazaki from his films: wise, avuncular, paternalistic, playful, insightful, with a hint of the grumpy wizard. In creating My Neighbor Totoro, Miyazaki had hoped to follow a string of heavily European-influenced fantasy adventure films (Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind; Castle in the Sky) with something closer to home. Literally so, as Totoro’s setting was partly inspired by the landscapes around Miyazaki’s family digs in Tokorozawa, a commuter town 30 kilometers outside of the bustle of Tokyo. In his directorial memoranda for the project, Miyazaki laid out a Totoro manifesto, pledging to uncover:

What we have forgotten

What we don’t notice

What we are convinced we have lost.

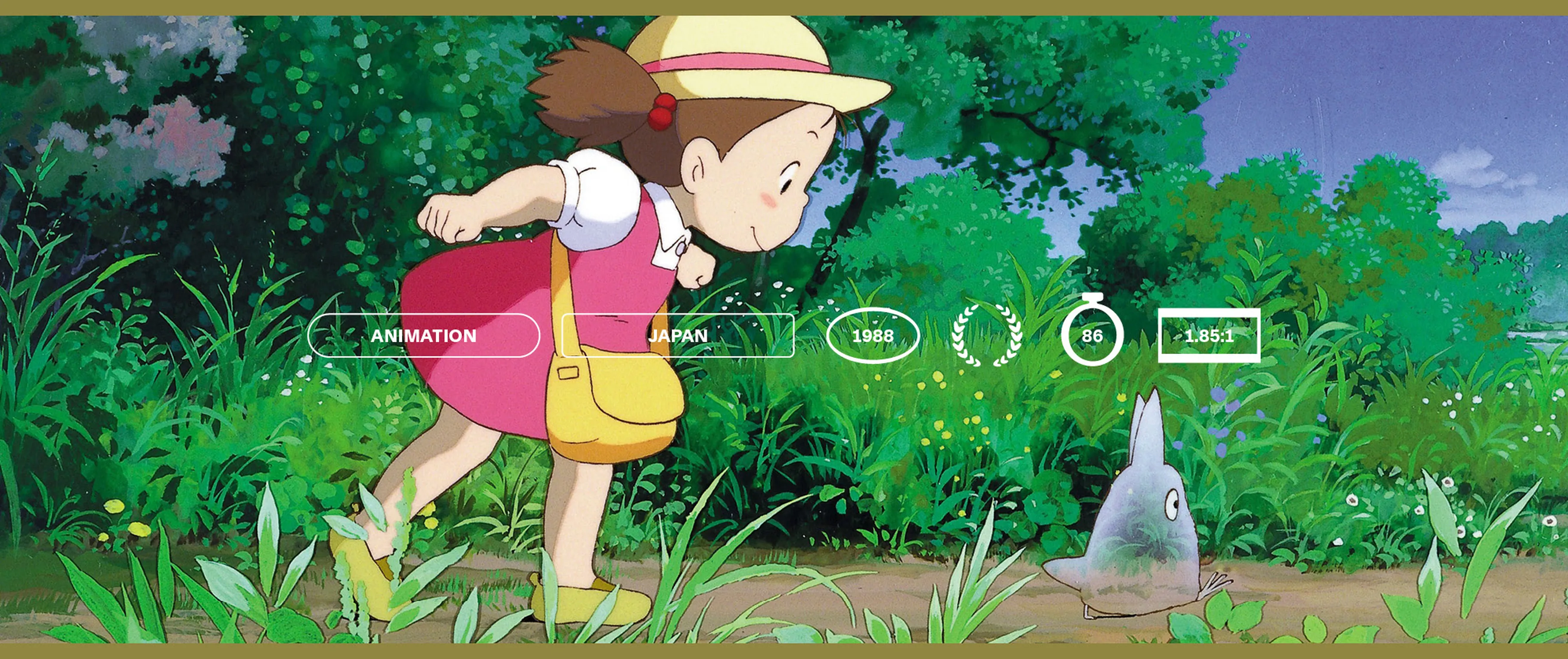

It’s fitting, then, that so much of My Neighbor Totoro’s compact 86-minute run time is dedicated to the simple acts of looking and seeing, particularly through the eyes of imaginative, curious young children. The peppy opening theme, “Hey, Let’s Go,” encourages us to “explore the deep and wonderful woods all day,” with title cards showing little Mei confidently striding through a procession of twigs, leaves, spiders, grasshoppers and myriad other minuscule details.

.jpg)

As soon as they arrive at their new house, the sisters are off exploring, shouting out with infectious glee about what they find: “A bridge!” “Look at this! A tunnel of trees!” “Acorns!” Miyazaki shows, and we observe, both the girls and their discoveries as if led by their perspective—which tends to see the best in everything. When they gaze into the stream that runs by the edge of their garden, they don’t see the discarded bottle deep below; instead they’re entranced by the tadpoles. Even their new home—a fixer-upper, to put it mildly—is a wondrous space to explore. It might even be haunted!

Later, when Mei first spies one of the smaller Totoro creatures, she does so while staring through the hole in the bottom of a bucket—a viewfinder that focuses our attention even further. These magical creatures exist in the landscape; you just have to look for them. Stare into the darkness down a country lane, and the bouncing headlamps of a Cat Bus just might appear. If your senses are attuned, these wonders will reveal themselves.

The Japanese title of Whisper of the Heart (1995), another Studio Ghibli gem that captures the vivid imaginations of young minds, is Mimi wo sumaseba, or “If You Listen Carefully.” If you listen carefully to Totoro, you’ll hear the sublime sounds of raindrops pitter-pattering on the top of an umbrella, the songs of cicadas in the early evening, the sighing of wind through the trees.

These are profound, everyday pleasures that are placed on equal footing with Miyazaki’s magical monsters: the flavor of fresh vegetables, the joy of a family bike ride, the act of planting seeds and watching them grow. Those seeds were a gift from Totoro, who visits Mei and Satsuki at nighttime to lead them through a delicate dance ritual around the flower bed that causes an enormous tree to erupt in their garden (a breathtaking sequence led by Miyazaki’s trusted animator of all things flora, Makiko Futaki). In the morning shoots have indeed sprouted, but they stand only a few inches tall rather than dozens of feet. And yet the girls, in their childlike wisdom, have made the connection between Totoro’s fantasies and the very real wonders of nature. “I thought it was a dream!” Satsuki says. “But it wasn’t a dream!” her sister replies.

“These magical creatures exist in the landscape; you just have to look for them.”

My Neighbor Totoro is a guidebook for living life with eyes open to the magic of the mundane and the everyday—those small things that “we don’t notice,” as per Miyazaki’s original manifesto. It should come as no surprise that the film inspires such affection, or that devoted fans want to incorporate Totoro and its iconography into their lives. I’m sure that Miyazaki would prefer we celebrate that love by going out and searching for tadpoles, but many of us settle for the slippers, purses and pencils, to the effect of making Totoro a near-billion-dollar multimedia juggernaut. That’s yet another fascinating contradiction that epitomizes Studio Ghibli: that the company whose meticulously crafted films eulogize a beautiful yet precarious natural world is bankrolled by masses of merchandise.

And yet, unlike Disney and its empire of intellectual property, brand extensions and tie-in products, there’s something about My Neighbor Totoro that resists commodification. As a film, it is alive and ever relevant. It invites us to slow down and take notice. And as a character, Totoro is an emblem for a world and worldview filled with curiosity, imagination and the majesty of nature. With teeth.