In Loving Memory

By Sloane Crosley

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, dir. Michel Gondry, 2004

In Loving Memory

Sloane Crosley

Before apps and swipes, there was the prescient tech romance Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. But is it romantic?

August 1, 2024

AUTHOR READS

There’s a line from screenwriter Charlie Kaufman’s 2004 masterpiece, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, directed by Michel Gondry, that plays on a loop in my head. This line is not delivered by Jim Carrey, Kate Winslet, Kirsten Dunst or Mark Ruffalo. It comes when Carrey’s character, the melancholic Joel Barish, befuddled by his girlfriend’s (Winslet) inexplicable snubbing (surely the cruelest concussion ever filmed), seeks solace in his friends Rob (David Cross) and Carrie (Jane Adams). What do they think happened to make his girlfriend suddenly treat him like a stranger? Carrie wants to withhold the truth, but Rob wants to share the mysterious form letter they’ve received from a company called Lacuna, which states: “Clementine Kruczynski has had Joel Barish erased from her memory. Please never mention their relationship to her again. Thank you.”

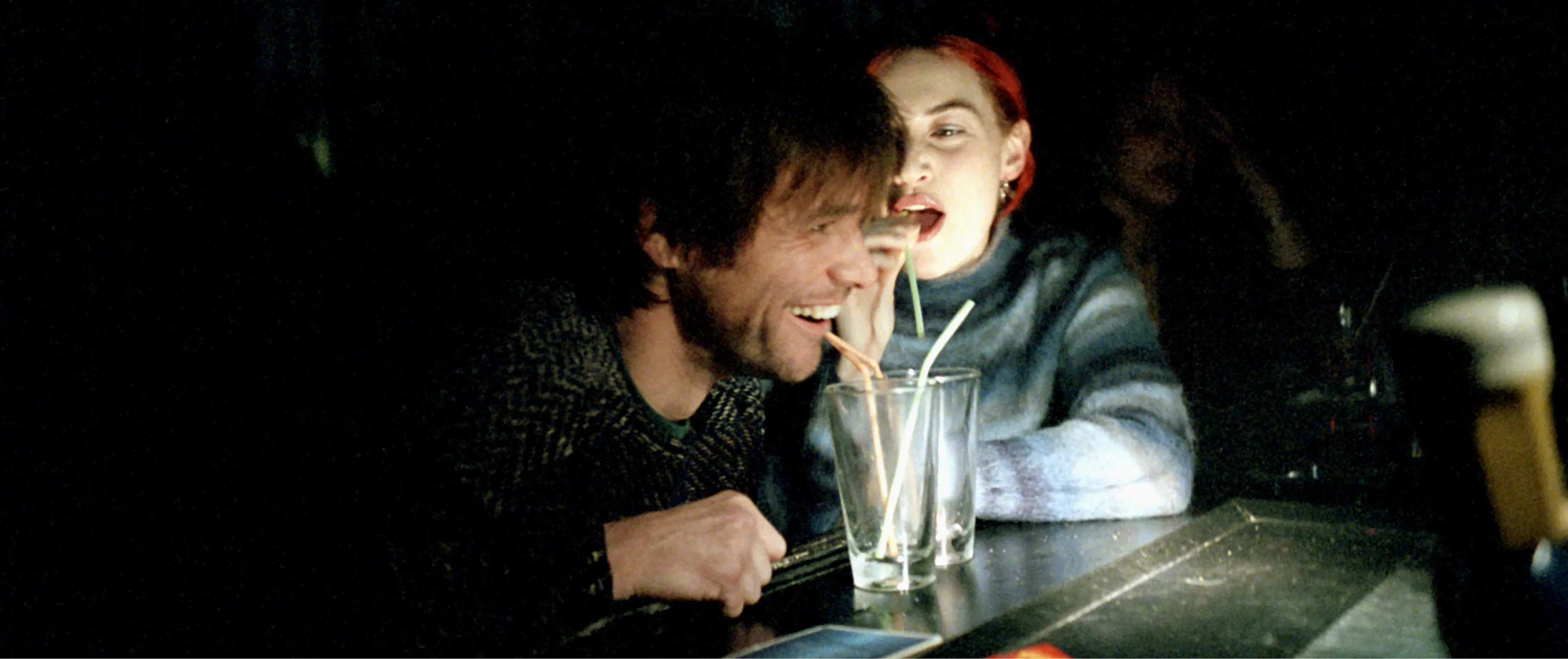

From left: Kate Winslet as Clementine; Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

The relationship between Rob and Carrie barely qualifies as a D-plot in Eternal Sunshine. Yet it serves as a perfect tribute to imperfect relationship dynamics. When I first saw the film, I thought very little of this middle-aged couple aside from their obvious narrative function. If anything, I thought: Theirs is not the relationship I’d want to be in—gimme one of them nonstop heart attack ones! Over the years I have come to realize that these two are the only ones in the film who would never erase each other on a lark, who have agreed to keep going through spikes of annoyance. At one point Carrie tells Rob to “give it a rest” as he hammers away on a home project in the next room. “Carrie,” Rob says, exasperation incarnate, “I’m making a birdhouse.”

That’s it. That’s my favorite line. It’s pleasantly retro-tech and guileless in a film that relies heavily on invented machinery to manipulate its characters.

Eternal Sunshine belongs to a specific post-9/11 genre of romance. Like 2002’s Punch-Drunk Love or 2003’s Lost in Translation, there’s a looming sense that the world has gone to pot and we, the audience, are watching two people stuck in the middle, isolated from their collective reality. All romantic stories share some version of this premise—part of finding love is the necessary exclusion of that which you do not love, fueled by a fear of loneliness—but the discrepancy between the hectic worlds of these films and the earnest lives of their central characters is more of a yawning gulf, fostering a desire in viewers to shield these fragile souls from an absurd universe that seeks to tear them apart. What makes Eternal Sunshine so revolutionary is how well it employs technology to address that gulf, to grant its darlings a perverse wish fulfillment. It blends humanity and innovation like no other modern romantic film before it. In fact it’s our most prescient love story, released during the time before apps and swiping, before pixelated little buttons allowed us to “mute” or “block” with ease.

Eternal Sunshine uses its gadgetry to both highlight the bond between the central characters and manufacture the chaos that hounds them. The technological innovation in question (a memory-erasing service with a physical office) is not merely the Screenwriting 101 obstacle on which the plot hinges but a gateway to the very soul of the film. At the risk of calling it a third lead, Lacuna has a sentience all its own. It asks us, Are we the sum total of our experiences or are parts of our history expendable? Are we doomed to repeat the past or blessed to repeat it? Will our natures compel us to search for love no matter how much damage we inflict upon ourselves and others? What even qualifies as a “good” choice?

If one envisions the contemporary genealogy of speculative romantic films—stories in which a group of people has access to a new form of technology or magic meant to fulfill the desires of its characters—one would include quite a few: Her, Ruby Sparks, Being John Malkovich, The Lobster, Palm Springs, Vanilla Sky (hey, everyone has that one cousin). Most of these films feature pronounced moments of disbelief on the part of their protagonists at the inflection point, when this bizarre technological invention offers the possibility of a life free from the fixed rules of “the real world.” Sometimes this disbelief takes the form of whole monologues of “You’ve got to be kidding me” and “I know this sounds nuts” that get repeated in small doses throughout the film. But Eternal Sunshine pointedly does not celebrate its transitional moment. It treats the whole memory-erasing service with little more than a shrug. When Rob hands Joel the Lacuna letter and Joel asks what it is, Rob responds: “I don’t know, it’s some place that does a thing.” Later, at the Lacuna offices, Joel does mutter his belief that it’s all a hoax, that “there’s no such thing as this.” But these are the only flashes of the film’s self-denial, handled swiftly.

Eternal Sunshine has bigger fish to fry. This unequivocal world acceptance is imperative for such high-concept films to succeed. If Eternal Sunshine has a worthy counterpart in terms of smoothness of conceit, then it’s Harold Ramis’s 1993 classic Groundhog Day. Both films deal with rides their heroes can’t get off of. Paradoxically, Groundhog Day ends with Bill Murray’s character, Phil, freeing himself from the repetition of his life, while Eternal Sunshine ends with Joel diving right back in.

![]()

Punch-Drunk Love, dir. Paul Thomas Anderson, 2002

![]()

The Lobster, dir. Yorgos Lanthimos, 2015

There’s even a lovely piece of overlap between the two films, during which a male character attempts to woo the female love interest by using the narrative’s wild laws. In the case of Groundhog Day, Phil attempts to reproduce, beat by beat, an organic date with Rita (Andie MacDowell). Snowball fights and first kisses included. In the case of Eternal Sunshine, Patrick’s (Elijah Wood) entire storyline involves him trying to artificially re-create the connection that Joel and Clementine once shared with each other. Neither is effective. Lesson learned: Just because the system exists doesn’t mean you can game it. Love remains a mysterious, unbridled force even for the cleverest practitioner.

For all the many character threads and structural tricks, Eternal Sunshine is a wonderfully efficient apparatus. Halfway through the film, Joel tries to override his own memory-erasing process, screaming that he wants to “call it off” and keep his memories of Clementine. In different authorial or directorial hands, this would come in the last act, because it would take that long for the characters just to grapple with the pitfalls of the new technology or to realize that the answer they were looking for was there all along. Whereas the first sounds of Eternal Sunshine are of van doors slamming; we later understand these were the sounds of the Lacuna technicians leaving Joel’s apartment. Thus, Eternal Sunshine starts at its destination, dropping us into the Lacuna maze before we even know we’re in it. Unlike other films, the majority of clues that something is amiss in this world—that this is not a “how we met” story but a “how we already met” story—are presented before we have a chance to question them. Such is the benefit of a movie that starts at the end and ends at the beginning.

The technology becomes part of the heartbreak, grafted onto the characters from the start. The reason Joel wants to stop the process is not because he is sick of being manipulated (as is the case for most wormholes, time loops, artificial intelligences or the insertion of one’s consciousness into a crustacean) but because he realizes that if he loses Clementine, he loses himself. Especially poignant is that it’s the most intimate memories that lead him to this conclusion, memories that should, in theory, be the most painful to keep. Such as the under-the-covers confession from Clementine that she thought she was ugly when she was a little girl. Joel kisses her, assuring her she’s pretty. He realizes these memories are worth keeping, even if Clementine never recognizes him again.

“Part of finding love is the necessary exclusion of that which you do not love, fueled by a fear of loneliness.”

Mechanics often overwhelm romance in speculative films. Filmmakers fixate on the bells and whistles of their newfangled invention, and as a result the beating heart of the characters gets lost. It never quite gels with the sparkly contrivance. When I think of Her, I think first of the screens and graphic design, of the operating system itself, not of the unique connection between Joaquin Phoenix and Scarlett Johansson. The specificity of their relationship is in the film; it’s just not in my memory. The same is true with Colin Farrell and Rachel Weisz in The Lobster, where I think first of the novelty of flamingos walking through the woods and creepy seaside hotels. I am a fan of these films, but the engineering of their escapism is stored in a separate place for me, away from their love stories. With Eternal Sunshine, a story about how we store memories, the threads are inseparable. When I visualize Winslet in her shaggy winter coat, being dragged away from Carrey by an invisible force, my heart breaks for them. There is, as Dr. Mierzwiak (Tom Wilkinson) puts it, “an emotional core to each of our memories.” This is true of the movie itself.

Ultimately, this effect has much to do with the way the tech itself is presented. The film’s more fantastical elements are all in Joel’s mind (the Montauk house crumbling, the childhood kitchen scenes, the rain falling in Joel’s living room). The actual technology employed by Dr. Mierzwiak and his slacker technician, Stan (Ruffalo), is refreshingly rudimentary. Stan drags what looks like a DVD/VCR combo player into Joel’s apartment. Joel, unconscious for much of the film, sports a helmet that is half cosmonaut, half kitchen colander. There’s some light banter about a “C-gate” when Joel goes off the MRI map, but really? We’re dealing with reams of computer paper. It’s lo-fi. The most far-fetched part of Eternal Sunshine is the idea that both Joel and Clementine would have all their friend’s mailing addresses.

“I’m making a birdhouse.” I feel certain that among the millions of people who have seen Eternal Sunshine, this is no one’s favorite line. It’s definitely not the most famous. That would be the hauntingly whispered “Meet me in Montauk,” uttered by Clementine near the end of the film, just before Joel wakes up. Perhaps the following is painfully obvious, but I only picked up on the narrative trick of “Meet me in Montauk” during a recent viewing: Because Clementine utters the phrase during the few seconds that go beyond memory and into imagination (Joel walks back to her as he did not in real life, when he ran from her down the beach), the line escapes the erasure of the technicians. It sticks because it’s new dialogue that he invented, not because it’s the last thing she says. It becomes the last thing he remembers. It’s also why he skips work to go to the beach in February (Clementine has been fighting a parallel battle for preservation, so she shows up too). This one line is the lynchpin for the film.

But is it romantic?

![]()

Groundhog Day, dir. Harold Ramis, 1993

![]()

Her, dir. Spike Jonze, 2013

There’s a longstanding argument that Eternal Sunshine is not a romantic movie, that it is rather a hellish one. Naysayers suggest that fans are not playing enough of a long game: Yes, these two find each other again, their sense of hope overpowering their fear of implosion—but then what? Is the implication that they keep erasing and finding each other in an infinite loop of loss and repair? This is where my beloved birdhouse comes in. By now my emphasis on it risks conjuring the They Might Be Giants song “Birdhouse in Your Soul” (great song, wrong reference), but for me it’s emblematic of the entire movie.

For one thing it’s about the mechanical care taken to build something so fanciful. Beautiful things don’t build themselves, nor do lasting relationships. No one needs a birdhouse. But if you’re going to make one, you should put your heart into it. Beyond that, every time I hear it, I hear it in the voice of a beloved ex-boyfriend, who also liked the line. During our relationship it became one of our in-jokes. He used to shout it when I’d ask what he was doing in the kitchen or if I texted him to ask if he’d be working late. “I’m making a birdhouse!” Some things will never be funny to more than two people, but I still find this to be hysterical, just typing it. We have both moved on but remain good friends, which means that, occasionally, one will text the other the line out of the blue, without context. We do it not because we want to go back in time. We do it because we have already been there. We do it because no one ever erases anyone, not really. And we do it because, phones in our hands, we have the technology to do it.