Jerry Schatzberg: Lens Legend

By Josh Siegel

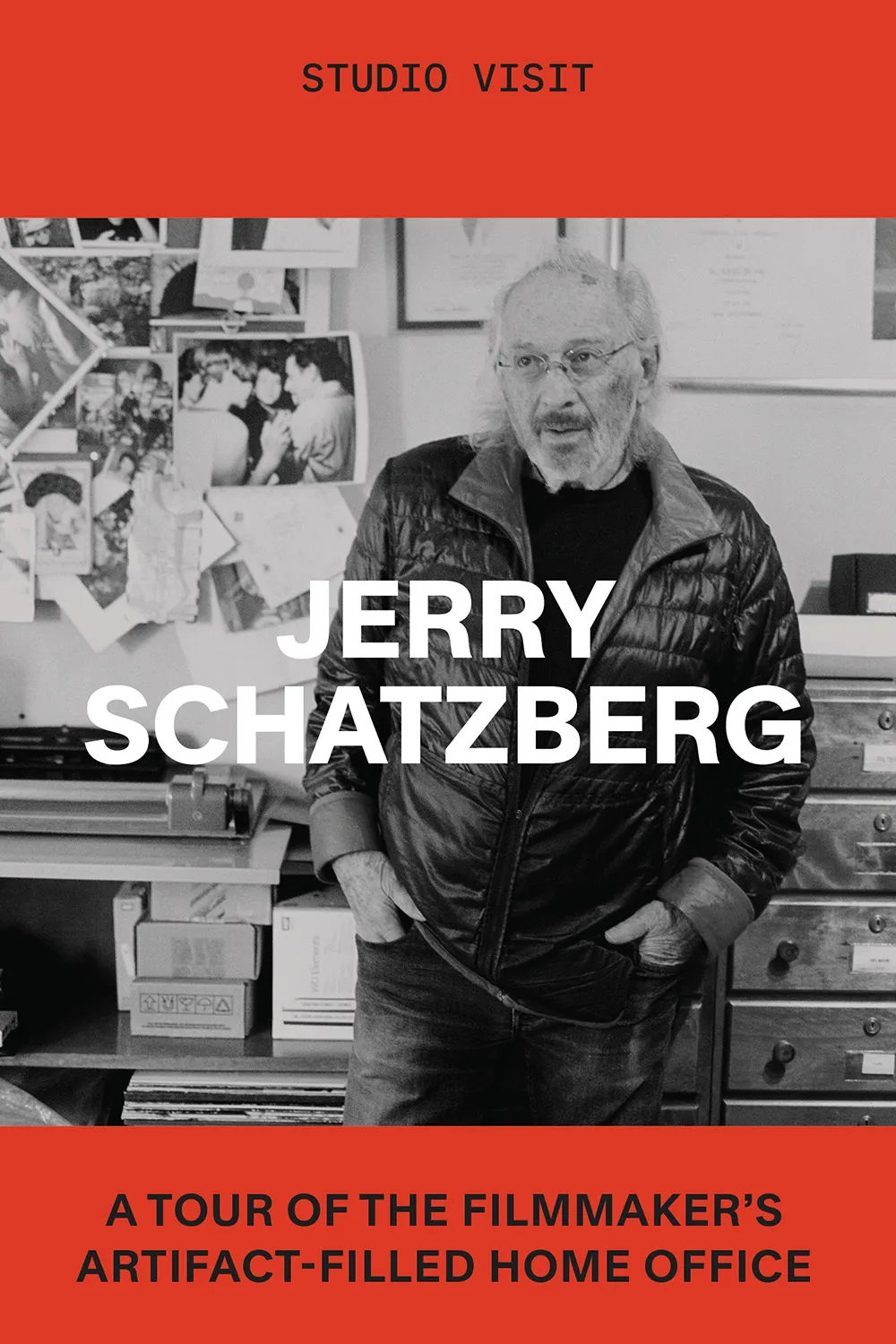

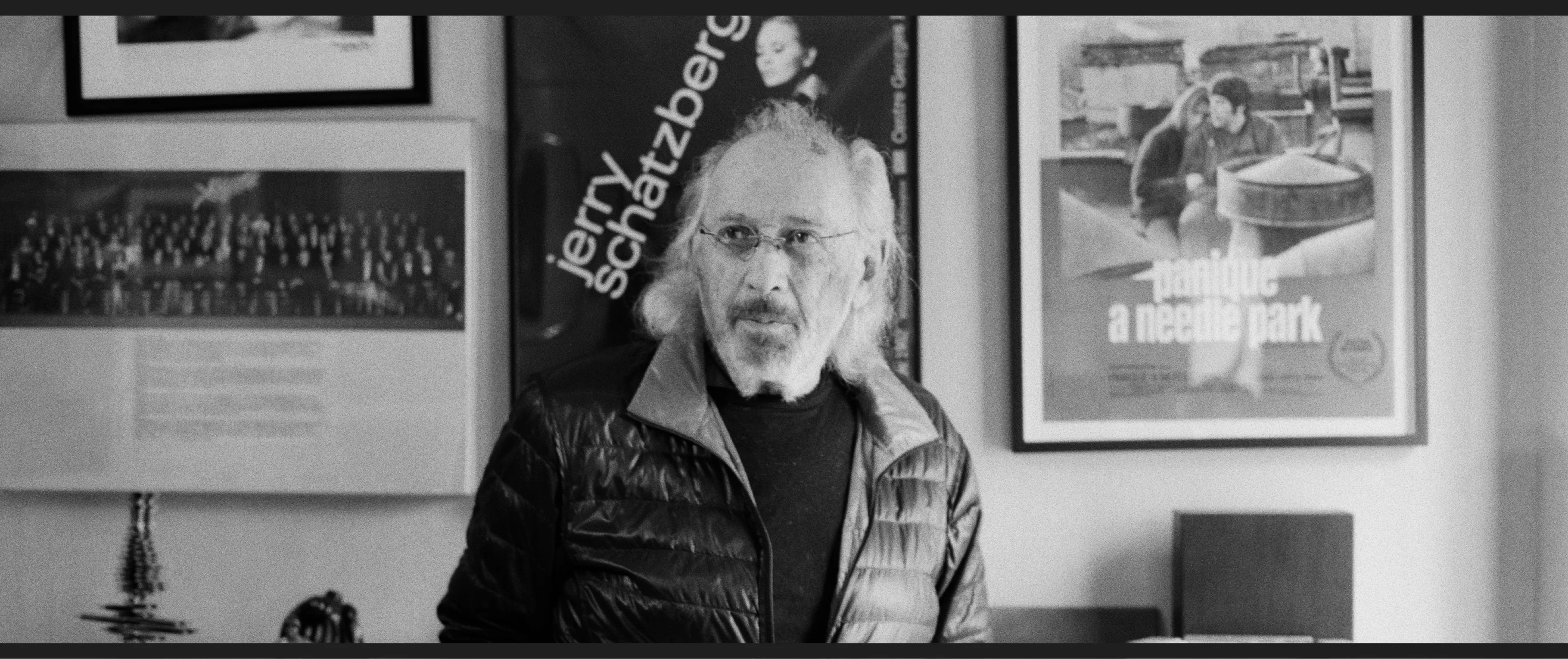

Jerry Schatzberg in his New York studio, 2023 (photo by Jennifer Steele)

Jerry Schatzberg: lens Legend

The renegade filmmaker and photographer talks through a trove of personal photographs—on assignment, unpublished or never-before-seen—and reflects on his storied career

By Josh Siegel

July 19, 2024

Photographs by Jerry Schatzberg

The filmmaker Jerry Schatzberg is the only almost-centenarian I know who can pull off a fedora with a braided Navajo trim, a leather bomber jacket, jeans, and an unbuttoned collar shirt revealing an ancient Chinese coin pendant in his chest hair. After decades spent photographing models, actors, rock stars and celebrities for Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue in their heyday, and then for a time hosting them at his nightclubs in midtown Manhattan (Ondine) and the West Village (Salvation), Jerry is always ready for his close-up. Even our habitual brunches near his apartment on the Upper West Side—he’s a regular at the Viand diner and Barney Greengrass—are a study in casual stylishness. He’s quick with a kind smile and a friendly word to a favorite waitress or a neighbor on the street.

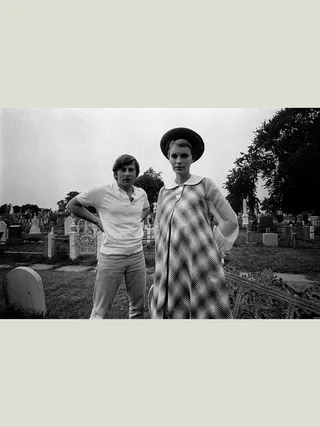

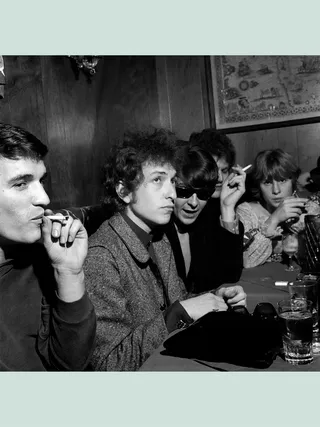

From left: Roman Polanski and Mia Farrow on the set of Rosemary’s Baby, Queens, New York, 1967; Faye Dunaway on the beach for Esquire, Florida, 1966; Bob Dylan at Ondine, New York, 1965

A middle-class Jewish kid from the Bronx (his father was a furrier who left Austria at the age of three; his mother a homemaker who put up with her husband’s reckless gambling habit), Jerry could have ended up taking over the family business after a stint in the Navy. But instead, at 27, he took up photography, not knowing the business end of the camera from the back, and through a winning combination of moxie, innate talent and sheer luck, managed to catch the attention of some of the leading fashion photographers and magazines of the late 1950s. Today, his pictures of Bob Dylan, Edie Sedgwick and Anne St. Marie are in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art and exhibited in museums the world over.

He was a latecomer to the movies. He made his first in 1970, at the relatively seasoned age of 43. Puzzle of a Downfall Child is the fractured portrait of a fashion model picking up the pieces of her life. As was so often the case among the New Hollywood directors of the 1970s, the feature caught the attention of French film critics before Americans took notice. Jerry has always had a way with putting actors and models at ease, capturing them in moments of vulnerability and tenderness, and Faye Dunaway’s performance in the film is one of her very best. Captured by Jerry’s lens, relative unknowns did not remain so for long: Roy Scheider in Puzzle; Al Pacino, Kitty Winn, Raul Julia and Paul Sorvino in The Panic in Needle Park (1971); Ann Wedgeworth in Scarecrow (1973); Meryl Streep in The Seduction of Joe Tynan (1979); Willie Nelson in Honeysuckle Rose (1980); Jon Cryer, Demi Moore and Tim Robbins in No Small Affair (1984). Those who already seemed incapable of giving a bad performance gave great ones: Gene Hackman in Scarecrow and Misunderstood (1984), Morgan Freeman in Street Smart (1987), Jason Robards in Reunion (1989).

For this interview, I sat down with Jerry in his unpretentious prewar apartment-cum-office on Central Park West to discuss his storied careers in still and moving pictures. I invited him to use specific photographs as a window on to his memories. His miraculous studio manager, Gabriella Goldberg, managed to call up a singular photograph among thousands in seconds from the digital archive, and Jerry told stories about them, becoming no less vulnerable and tender than the images he drew out of his actors and photographic subjects. That many have since died was painful for him to recall. But even when discussing some of the most glamorous talents of the 20th century, he was, throughout our conversation, the same regular kid from the Bronx he’s always been: a mensch. —Josh Siegel

Jerry Schatzberg, age 11, with his camera, New York, 1938 (photo courtesy of Jerry Schatzberg Archive)

STARTING OUT IN DIAPERS

Let’s talk about diapers. You got your start taking pictures of baby’s bottoms, right?

I was very unhappy when I got out of the Navy. I ended up asking my father if he had a job for me, and I didn’t really get along with my father. He taught me how to ride a bicycle when I was very young. He taught me how to drive a car. But the father things that I might’ve wanted were not there.

Anyway, they have these fire escapes that are just little terraces outside commercial buildings on Seventh Avenue. One day I was having a sandwich there and I saw an ad for a photographer’s assistant in the Times. I didn’t know what that was, because I wasn’t a photographer. I figured, well, I’ll see what it is. I ended up visiting a photographer’s studio. He was on his way to Paris at the time. I was very impressed with his studio. All black and white, touches of red. They interviewed me and offered me only $25 a week because I had no experience. I said, “Oh, boy, that’s pretty tough. Because I am married. I have one child and another one on the way. I don’t think I could take that job.” So instead I had an uncle who worked for a company that rented diapers by the month…

Because they were cloth diapers. They would have to rewash them and circulate them around town.

Exactly. And if you rented their diapers, you got a free picture of your child. The child was usually not even a month old. My uncle sold the pictures door-to-door, and he said there was no money in taking the photo. I think you got $2 per sitting. And I said, “How many sittings do they give you a day?” He said, “Usually between 10 and 20.” I said, “It’s much more than I was offered for an assistant job.” I borrowed money from my mother to buy a Rolleiflex camera and got the job. I spent days looking at the instructions, trying to make the camera work. My territory was Long Island. The first place I went to, they wouldn’t let me in because the baby was sleeping. The next place, they wouldn’t let me in because the baby was sick. I’d end up doing maybe two sittings a day. And my uncle said, “I told you there’s no money in it.”

fashion beginnings

![]()

Anne St. Marie in Jerry’s studio, New York, 1958

![]()

Anne St. Marie in New York, 1958

But with that camerawork you eventually got hired to work for more prominent photographers, including shooting fashion models. And that led to your first big break, right?

Bill [William] Helburn was a very well-known commercial and fashion photographer. He worked for Charm magazine. He hired me and showed me what to do. In those days you used an 8x10 view camera for color, and you used a 4x5 view camera for black and white. I would get on the side of the camera, and I’d be pushing and pulling the slides and turning them the wrong way. Bill was getting more and more annoyed. Finally he picked up his light meter and threw it against the wall. He said, “I don’t think I can do this.” And a stylist said, “Come on, Billy, he’s here three weeks. Give him a break.” So I made sure I learned. I knew I had to really shape up. I ended up working with him for two and a half years.

When I told him I was leaving, he offered me a piece of the business. Models needed photographs and I needed photographs. So it was an even exchange. They would take my photos around in their look book to get work. That’s how my name started getting around. Then I got a call from Vogue and they said, “Can you come in and see Mr. Liberman?” So I went. Alexander Liberman was very nice, an extraordinary gentleman, very elegant. When I was leaving his office, he says, “I think I’m going to give you some work.” By the time I got back to the studio, he had already called to give me my first assignment.

DUNAWAY & DENEUVE

![]()

Catherine Deneuve for Esquire, Paris, 1962

![]()

Catherine Deneuve for Esquire, New York, 1965

![]()

Faye Dunaway for Esquire, Florida, 1966

How did you take these early photographs of Faye Dunaway?

I had become friendly with Faye and was asked to do a story on her in 1966 for Esquire. We did a few shots on a bed and went out to the beach. She was doing one of her first films then, The Happening [1967]. She was a new model and very excited. In the middle of the shoot, she started crying. I didn’t know what I had done. “Did I say something?” I asked her. “No, no, no, don’t worry, this happens.” The same thing happened with Catherine Deneuve when I shot her in 1965. Catherine just started to cry. I think there’s a certain sensitivity that both have that just takes over. I still don’t know why. I had to stop shooting until they wiped the tears away.

Deneuve was already well-known when you shot her portrait, but Dunaway was just getting her start. Did you build a relationship with your subjects before you start taking pictures, or do you just plunge into shooting right away?

No matter who I would photograph, whether it was a personality or a politician, I would always take them into my office and talk to them for as much time as possible, just becoming friends. For Faye, word was getting around that she was up-and-coming. So I tried my best to talk to her, and we ended up becoming buddies before I shot her.

You wanted to put your subject at ease.

Yeah. And myself too. It’s not come in, sit down and bang, bang, bang, you’re finished. I mean, when I photographed Dylan, when I photograph anybody, I would talk to them first to put them at ease and put myself at ease and watch them to see how they move, what I could expect from them.

FROM PICTURES TO MOVIES

From left: Carolyn D’Annibale and Bob Smith in New York’s Central Park, 1959; dancer Suzanne Farrell in New York, 1964; Anne St. Marie in New York, 1962

Still photographs often appear in the backgrounds of your films. In Puzzle of a Downfall Child, several photographs appear on the wall of the studio, including the picture you took of an African American boy on a park bench and one of Dunaway sitting on a rock in Central Park. Another photograph is of the great Balanchine dancer Suzanne Farrell.

These were the first pictures taken of her. Then she was at the New York City Ballet for years.

You incorporate wonderful freeze-frames in the film to evoke still photographs. Tell me about integrating still images into your movies, as well as your relationship with the model Anne St. Marie. Your connection set the project of Puzzle in motion.

Anne St. Marie was one of Bill Helburn’s favorite models. She came to the studio a lot and we became great friends. I was an assistant, she was a model. At one point she said, “Listen, whenever you need a model to do something, I’ll help you out.” She was just fantastic, a natural. It’s very difficult not to take extraordinary photographs of her. The big models knew what they were doing.

I have two and a half hours of audio tape of Anne that I recorded later on when I knew that she would be the model for my fashion model in Puzzle. She had a breakdown while modeling. And this photograph was one of the ones I took while she was in the middle of her breakdown. I sort of became her guardian. I knew she was having problems and I was trying to help her get back into shape again. I would also see her a lot like this, without makeup. No one wanted models as old as her.

You have that touching scene in Puzzle when Faye realizes she’s past her prime, showing up wearing that wonderfully garish green eyeshadow only to find she’s been usurped by a new, young model.

There’s also a series of photographs I did on Millie Perkins. Millie was a young actress and I think she did a little modeling. She had terrible eyebrows. And I asked Anne if she would help me shape Millie up for some photographs at my studio. She did, and that was part of the sitting. And this is a friend of mine, the sculptor Paul von Ringelheim. He was always coming into the studio. I used his sculpture of a cross in a lot of my Dylan photos.

How did Faye get involved with Puzzle?

I had a very personal relationship with Faye, and I brought her the idea and she fell in love with it. So she was basically in it right from the start. Initially we had a French writer on the script. He was not bad, but he had such an ego that I just couldn’t put up with him. So I thanked him, paid him, and he went off. I tried another writer who gave me a terrible script. But Anne and Faye were always involved in the project. Faye would ask questions and Anne would answer them.

You ended up with Carole Eastman, a wonderful screenwriter who had already done Five Easy Pieces and The Shooting.

She had made two films with Jack Nicholson. She was friends with Jack. When she died in 2004, Jack did the memorial at her funeral and everybody was crying. One day I was in an elevator on my way to visit Faye, and a voice from behind me said, “You’re Jerry Schatzberg, aren’t you?” I turn around, I see this guy, and he goes, “We met in New York at a cocktail party.” He ended up telling me about this great screenwriter, and when I read a script she had written, I said, “I must have this writer.” At this time Ismail Merchant was interested in being a producer of the film, and I told him we had to make a deal with her. He said, “Well, I can’t do it right away, because I’m working on this film with James Ivory. As soon as I can, I will.” It went on for a while. I kept calling him. I became a real pain in the ass. Finally I said, “Ismail, I can’t wait any longer. I’m moving on.” And I did. I rented a house in L.A. and tried to get the ball rolling on the film. That writer, of course, was Carole.

How was being out in L.A.?

You know, I was friendly with Roman Polanski, who had a house out in L.A. He was in London at the time. He said, “Well, Sharon’s going to meet me in London. Why don’t you take our house?” I thought about it for a while, and I said, “I’ve already rented a house. I’ve paid everything. It’s a little bit late, but thank you.” And we know what happened.

Wow. I’ve heard stories of people who were meant to be at the Polanski-Tate house at the time of the Manson murders.

I called Carole and asked if she’d come see me. She came, and when she walked in, she said she was taking her friend to the dentist, and her friend was already waiting in the car. “She’s got a very bad toothache,” she said. I wanted to play the tape of conversations with Anne for her. Carole asked, “How long will it be?” I said, “The tape is about two hours.” “No. No, I can’t.” I said, “Well, how long can you stay?” “Five, 10 minutes.” So I put it on and she sat through the whole two hours. She knew she had to be part of it.

That’s great.

And her friend was still waiting in the car.

THE PANIC IN NEEDLE PARK

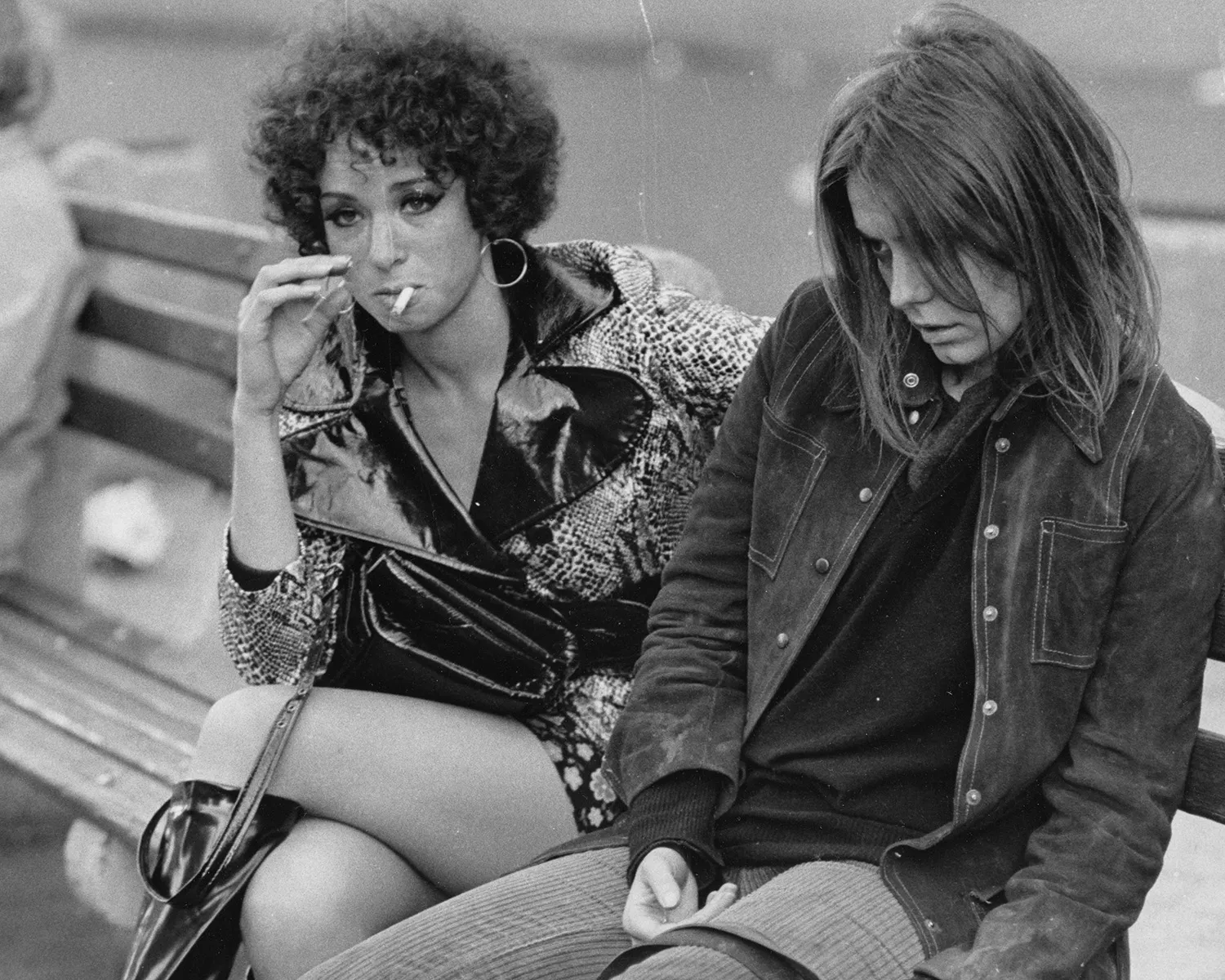

On the set of The Panic in Needle Park, New York, 1970 (images by Adger W. Cowans)

In your portfolio, you have this jarring juxtaposition of haute couture images of models alongside shots of homeless people on grungy New York streets in the 1960s and ’70s. It seems to mirror the transition from Puzzle to The Panic in Needle Park.

Panic was my first commercial film. Or at least the first film I didn’t initiate. I had met Dominick Dunne out in California, and I was sent the script by the Dunnes [Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne]. I read the script and turned the film down because the lab had scratched the last six minutes of Puzzle. I really had it in my mind to do only one film. I wasn’t going into the film business. But I had seen Al Pacino onstage a few years earlier, in Israel Horovitz’s The Indian Wants the Bronx. Al and I had the same business manager, Marty Bregman. Al was dynamite in that play. When Marty and I went backstage, Al was this really sweet guy, a pussycat. I said to Marty, “Boy, if I ever did a film, that’s a guy I’d like to work with.” Now I’m at Marty’s office and he says, “There’s a good script out there. It’s called The Panic in Needle Park.” I said, “I’ve read it, but I’m so disappointed with the lab scratching my negative. I don’t want to be in this business.” He said, “Well, Al’s interested.” That’s all I had to hear. I went home and read the script again. Then I called the writers.

Not just any writers. Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne. What happened when you called them?

I apologized, and they were a bit standoffish. They didn’t want to give in to me too easily. I explained what happened to my first film with the scratched negative. So they said, “Okay, let’s start over.” So we started over. We got Al, and Al recommended so many wonderful actors that I used in the film.

How much of the original script made it on to the screen?

I had a lot of trouble with the dialogue. I just didn’t think that the actors were right saying some of those lines. So I changed the lines. If Al is saying something that Steve McQueen might have said, I’d have to change it. Dominick [John Gregory Dunne’s brother], who was the producer, would see the dailies and become furious. He’d just walk out. But I couldn’t help myself.

How much research went into the making of the film? How much time did you spend with junkies and dealers?

A lot.

Did you go see them with Al?

Oh, yeah. Al was not working much at the time. He had about two or three months off. Kitty [Winn, who costars in the film] went back to California because she was in a repertory company. But I would tell her what we were doing. We’d send her a new version of the script, and if she had any comments, I’d work with her on the phone and then with the writers. I didn’t change the attitude of the film. I changed dialogue. So from the time I get up in the morning to the time I go to sleep, I’m visiting people, talking to all these actors and people that I know who are junkies, and then I call the Dunnes and say this and this happened. I wanted to get it right for the actors.

How did you do the scenes where people are shooting up?

I did have two or three actual needles onscreen, but we’d use salt water or sugar water. That’s what they were shooting up. The close-ups were of real people, but I wasn’t shooting drugs into them. I told the cast and crew the first day, “No one is allowed to do drugs on set.”

The film is almost a documentary record of the Upper West Side in 1971. I love seeing the Alamac Hotel and the Pick-n-Pay, which doesn’t exist anymore. And the old buses from my childhood.

Every time I passed Sherman Square [the triangular island bounded by Broadway, Amsterdam Avenue and West 70th Street], that was Needle Park. I wanted to shoot down on the actors, so Adam [Holender, the cinematographer] and I went up in this new apartment building that was being built on Broadway and crawled on our bellies onto the terraces—they were just platforms at that point—right to the edge to shoot. That’s where I shot that scene where Kitty is running down the street, looking for Al.

You were shooting from a construction site. Tell me about Kitty. She was extraordinary.

She was wonderful. The way she comes off at the beginning of her character, she was like that in life. She was a schoolgirl, just on the edge of wanting to try things.

How did you protect these actors?

From what?

You’re dealing with some pretty scary things, and these are new, emerging actors.

We were basically left alone, even though we were out in the streets shooting. New York is very sophisticated that way. I just think I had good actors. But I’ve always been very careful.

Faye is another example. I imagine she was very fragile.

She was already doing a film with Michael Parks and Anthony Quinn [The Happening]. She got into trouble by letting her management make five-year deals for her. She had one with Otto Preminger that they had to pay off [after they made Hurry Sundown]. She had a very difficult time with him. I don’t blame her. When Panic was getting some good word, I got a call at the office: “Mr. Preminger would like to see the film.”

Preminger wanted to see Panic.

Yeah. He came, the theater was empty. The whole crew was there, and I introduced myself. He didn’t know who I was. He took a seat. He watched it. As soon as the end came, he just got up and walked out. Didn’t say thank you to anybody, just...Ah, fuck him.

It was a passing of a generation. It was a very different style of acting and filmmaking.

I watched The Man with the Golden Arm last week on television [Preminger’s film in which Frank Sinatra plays a junkie]. And I don’t know, he just might not have liked Panic.

There’s a beautiful sequence in Panic on the Staten Island Ferry, your use of silence and the lapping of the water and then the sudden violence of the puppy jumping off the boat.

Everybody wants to know what happened to the dog. And I keep telling them, “He drowned.”

The seeming authenticity of your characters and locations in your movies seems to stem from your encounters in street photography. You’ve done some great casting of nonprofessional actors in your films. I’m thinking for example of the older woman in Panic who plays the pawnbroker who haggles with a desperately strung-out Al Pacino, or the wonderful striptease scene with Gene Hackman and all the barflies in Scarecrow.

Those were nonactors. I went into that bar and said, “Okay, now you got a day or two of work, but you can’t drink. We’ll give you fake drinks, but you can’t have real drinks for these sets. And when I want noise, you give me that noise.”

OBSERVING REAL PEOPLE

![Rod Steiger on the set of <i>The Pawnbroker</i> in New York City, 1963]() Rod Steiger on the set of The Pawnbroker in New York City, 1963

Rod Steiger on the set of The Pawnbroker in New York City, 1963![Four boys walking in Manhattan, 1963]() Four boys walking in Manhattan, 1963

Four boys walking in Manhattan, 1963![Children sitting on a Manhattan sidewalk, 1973]() Children sitting on a Manhattan sidewalk, 1973

Children sitting on a Manhattan sidewalk, 1973![Two girls selling necklaces in New York City, 1981]() Two girls selling necklaces in New York City, 1981

Two girls selling necklaces in New York City, 1981

Let’s look at your Pawnbroker series. How did this assignment come about?

I was introduced to Sidney Lumet. He was a good director. His films are terrific. I got an assignment to take still pictures. I took the actor Rod Steiger up to Harlem to give him the idea of the pawnbroker and what they go through and what their life is like.

The Pawnbroker is a groundbreaking film. It was the first Hollywood film to depict a Holocaust survivor from the survivor’s point of view. Steiger gives a terrific performance. I’m not surprised he did immersive research into the role. But the project was more like street photography for you.

Yeah, that’s what it was, basically.

NEW YORK NIGHTLIFE

![Berry Gordy dancing at Ondine, New York City, 1965]() Berry Gordy dancing at Ondine, New York City, 1965

Berry Gordy dancing at Ondine, New York City, 1965![Andy Warhol for <i>Town & Country</i>, New York City, 1966]() Andy Warhol for Town & Country, New York City, 1966

Andy Warhol for Town & Country, New York City, 1966![Edie Sedgwick in Jerry’s studio, New York City, 1966]() Edie Sedgwick in Jerry’s studio, New York City, 1966

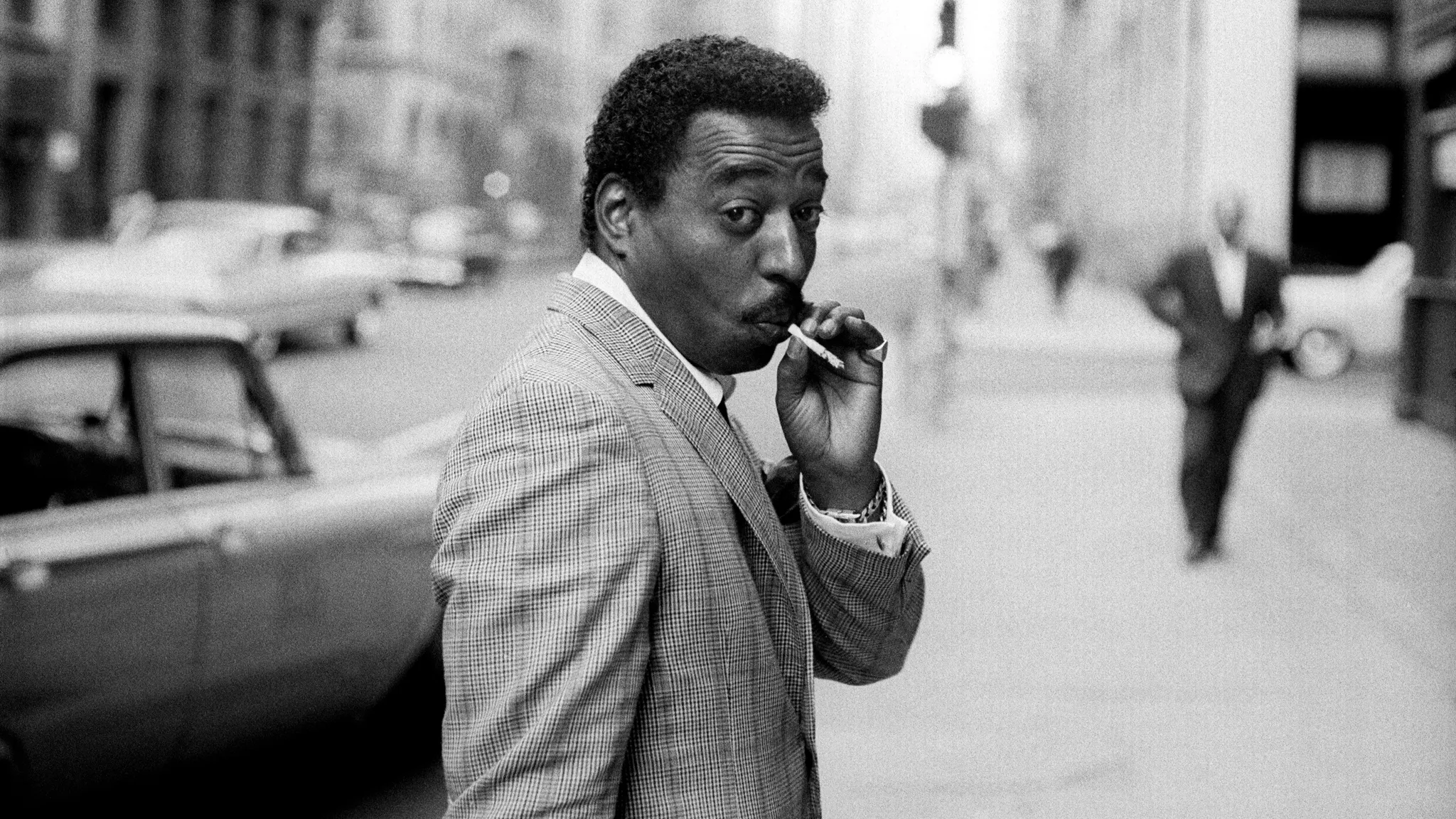

Edie Sedgwick in Jerry’s studio, New York City, 1966![Jazz drummer Chico Hamilton walking in Manhattan, 1962]() Jazz drummer Chico Hamilton walking in Manhattan, 1962

Jazz drummer Chico Hamilton walking in Manhattan, 1962

You owned your own clubs in New York, Ondine uptown and Salvation in the West Village.

Yeah, Ondine was on East 59th Street, under the bridge. I went in with a guy who was French. He had opened a club called Le Club in a studio. And one night he asked me if I wanted to invest in a new club he was opening. Lots of people came. Some of these shots are from inside the club. This is Berry Gordy.

You had a lot of Motown folks show up.

The Animals. The Supremes. The Ronettes. There was also Baby Jane Holzer.

It was a wonderful collision of Detroit and the Factory.

There’s Dylan and the actress Bebe Neuwirth. I had him there with some of the other boys. The Rolling Stones were there. They all came to the club and danced.

How long did it last?

A year or two. Then a guy came in and bought out most of the partners.

Did you go to Max’s Kansas City?

All the time.

I know you went to see a lot of musicians play. How did you manage to get Miles Davis for the score of Street Smart?

He used to see me all the time. I’d be at the first table right underneath him at Birdland. So he knew me, and I remember he was having trouble with his band and he left the stage and went over to the bar, and Chico Hamilton [the jazz drummer] was there, who was a friend. I said hello to Chico. And Chico said to Miles Davis, “Do you know Jerry?” That’s when he looked at me and said, “Yeah, I know that motherfucker.” He didn’t know me. He knew me sitting in front of him.

You got a terrific score out of him.

Robert Irving III did the score, and then Miles came in to do his spot. I just told him what I wanted.

Which is a lot like how Louis Malle got the all-night improvised recording session from Miles Davis for Elevator to the Gallows. It’s a wonderful counterpoint to Miles Davis’s film career, because they’re both films with unforgettable scenes of streets at night.

It’s true. I hadn’t thought of that.

Can you tell your story about Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick?

I was friendly with Edie. I knew all of Andy’s superstars. I didn’t hang out at the Factory very much, but I knew all of them. A lot of them came to Ondine. But Albert Grossman, who was Dylan’s manager when I did my first photographs of Dylan, asked me if I would photograph Edie Sedgwick. I said, “Sure, she’s a friend. Why do you want them?” And he replied, “I think she’s just a character I’d like to have photographs of.” So I was walking up Park Avenue South. And I see Andy coming down the block with a photographer, Barbara Rubin.

Barbara Rubin’s also the filmmaker who made Christmas on Earth in 1963.

Yeah. We stopped and talked, and Andy, with his old Andy enthusiasm, asked me, “What are you doing?” I said, “Oh, well, I just agreed to photograph Edie.” All of a sudden, his face changed. Because he thought he owned her. I said, “Yeah, I’m going to photograph her for Albert Grossman.” “Oh yeah, yeah.” And we talked a little bit, but then I saw that he wasn’t too interested in sticking around. When I got back to the studio, I got a call from Barbara Rubin: “Andy asked me to call you. Would it be all right if he came to photograph you photographing Edie?” And I thought, He doesn’t want to be left out of anything. “Yeah, it’s okay.” Five or 10 minutes go by and she calls again. “Is it alright if I come up with Andy to photograph Andy photographing you?” I said, “Yeah, you can all come.” Forty people showed up.

Forty people showed up? The entire Factory?

Including the Velvet Underground. I said, “I can’t do this.” So I took Edie, Andy, Gerard Malanga and Barbara Rubin into the dressing room. I said, “Okay, we’ll shoot in here.” I was up front and Barbara was in back and Andy was sort of in the middle. And from a distance I hear Gerard say, “But, Andy, there’s no film in the camera.” Andy sighs and says, “It doesn’t matter.” Typical Andy.

“And Chico said to Miles Davis, “Do you know Jerry?” That’s when he looked at me and said, ‘Yeah, I know that motherfucker.’ He didn't know me.”

PACINO AND HACKMAN

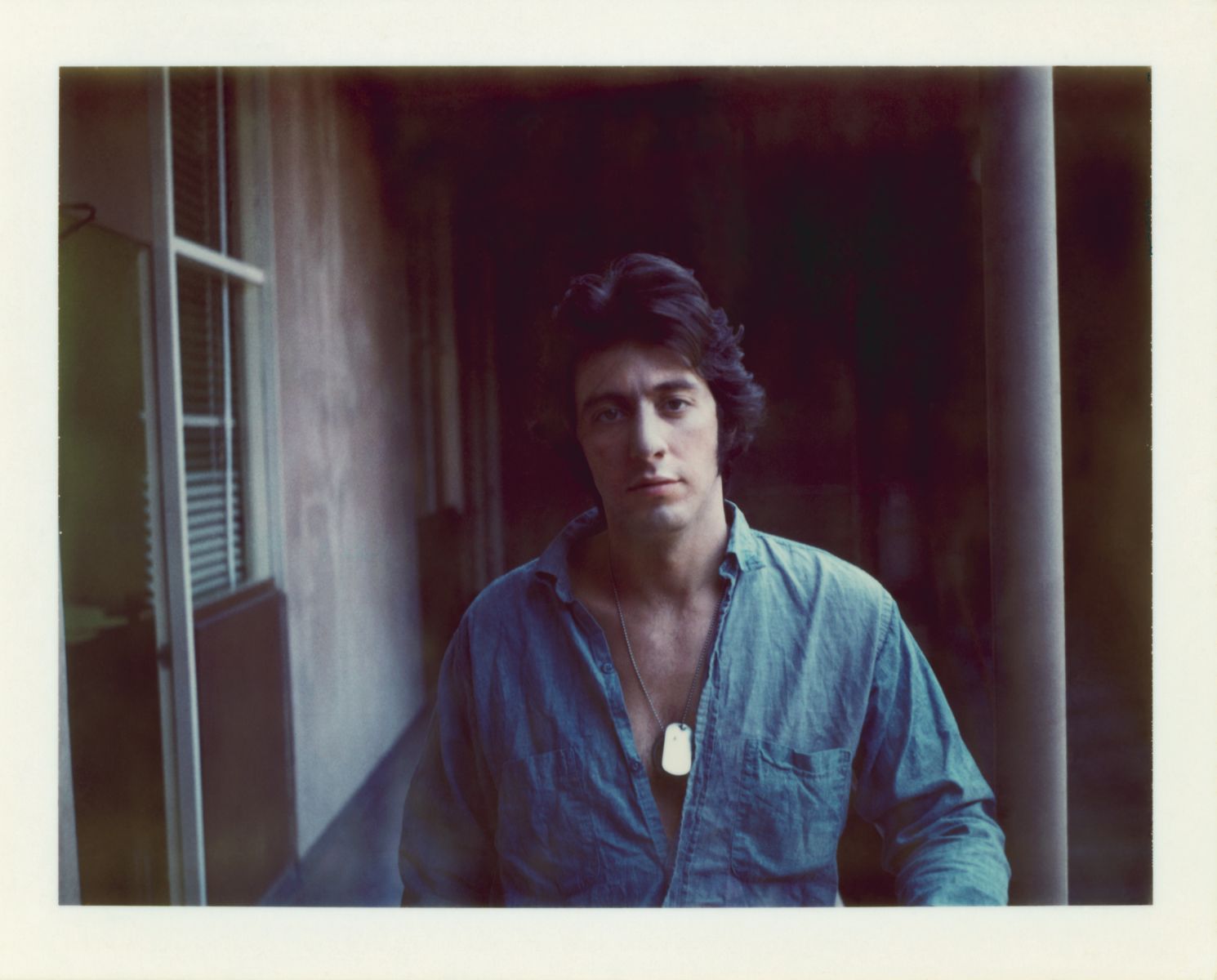

Al Pacino on the set of Scarecrow, 1972

I want to ask you about Scarecrow, particularly about the stylistic differences between Al Pacino and Gene Hackman in that film.

Hackman was the ultimate professional. He was always on time. He knew his lines. Pacino is just the opposite. Pacino would come 15 minutes late to the shoot, and it would annoy Hackman. He figured he’s just as important. But Al didn’t get affected by that. He didn’t know he was doing it. I came to shoot one morning and said, “Why don’t we go through the scene? I think there’s a lot of dialogue that’s superfluous.” Hackman turned around and started walking away. “Oh, fuck,” I said. “Hold it. What’s the matter?” “Nothing, nothing. Let’s go.” I said, “No, no, what’s the problem?” He said, “Nothing.” I said, “Gene, I don’t want you in that kind of mood when we’re going to shoot something. Let’s go into the alley and talk.” Gene wanted Al to go too. So we all go into the alley, and Gene turns around and says, “I’m sick and fucking tired of you guys deciding what my dialogue’s going to be the next day.” And I said, “Hold it. I don’t see him at night. I don’t see you at night. I don’t socialize with either one of you. I’ve got my homework to do, and I just do it.” Anyway, I didn’t realize when we went out to the alley that both of the actors were miked and the sound crew was listening to it. Had these kids around the sound crew having a great time.

Laughing their heads off. After that conversation, did Gene stick to his lines?

I would think. But Gene could improvise too. There’s a scene in Scarecrow where Al gets beaten up and he comes back to the dormitory where he’s staying and he’s calling out to Gene, but Gene is sleeping. Gene wakes up and leans on one elbow to see Al all beaten up and bloody and gets up to take care of his buddy. Gene said to me, “Tell the guy in that nearby bed that when I pass him, he should get up.” I didn’t ask any questions. So Gene throws off his blanket and gets up, and when the guy next to him tries to get out of bed, Gene stops him with a wave of his hand. He wanted to tell the guy, “Don’t worry, I got it under control.” Gene knows what the scene is. He knows that he doesn’t want to just be walking. He wants to have something to do.

You worked with Gene again in Misunderstood. In that film he also plays an absent father, an aloof father. Absent fathers are a theme in your films. Scarecrow and Misunderstood are provocative companion pieces. And Pacino’s and Hackman’s performances of that period always surprise and haunt me.

That’s the secret: Use good actors and you get good performances.

Tell me about this beautiful Polaroid of Pacino.

Al was walking and I said to the cameraman, “Give me a Polaroid.” So I got his Polaroid camera and I took this picture. It’s the only picture I took of him on the stage.

It’s a very beautiful photograph. The dog tags.

Yeah, I thought so.

In general, did you take still pictures when you were making films or was it too distracting?

No. Too distracting.

You worked with Al on two films.

I was always thinking of casting him. You know, Al tested four times for The Godfather, and they turned him down all four times. Francis [Ford Coppola] called me and asked if I had any footage of Al that I could lend him. So I sent him about 20 minutes of material. It’s from that footage that Al got the part.

LEGENDARY CINEMATOGRAPHERS

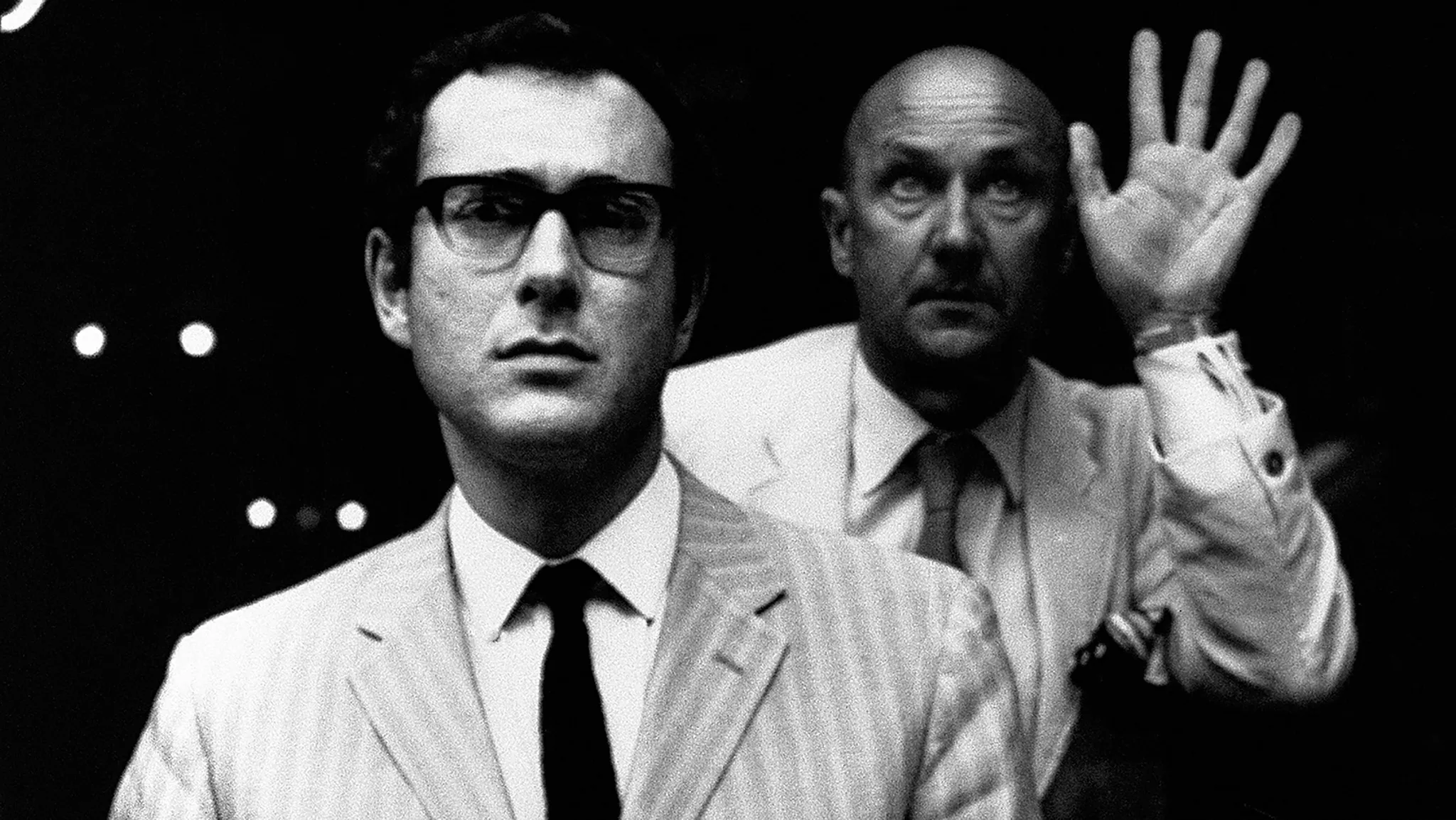

![Harold Pinter and Donald Pleasence for <i>Glamour</i>, NYC, 1968]() Harold Pinter and Donald Pleasence for Glamour, NYC, 1968

Harold Pinter and Donald Pleasence for Glamour, NYC, 1968![Adam Holender at Jerry’s upstate New York farm, 1989]() Adam Holender at Jerry’s upstate New York farm, 1989

Adam Holender at Jerry’s upstate New York farm, 1989![Roman Polanski on the set of <i>Repulsion</i>, London, 1964]() Roman Polanski on the set of Repulsion, London, 1964

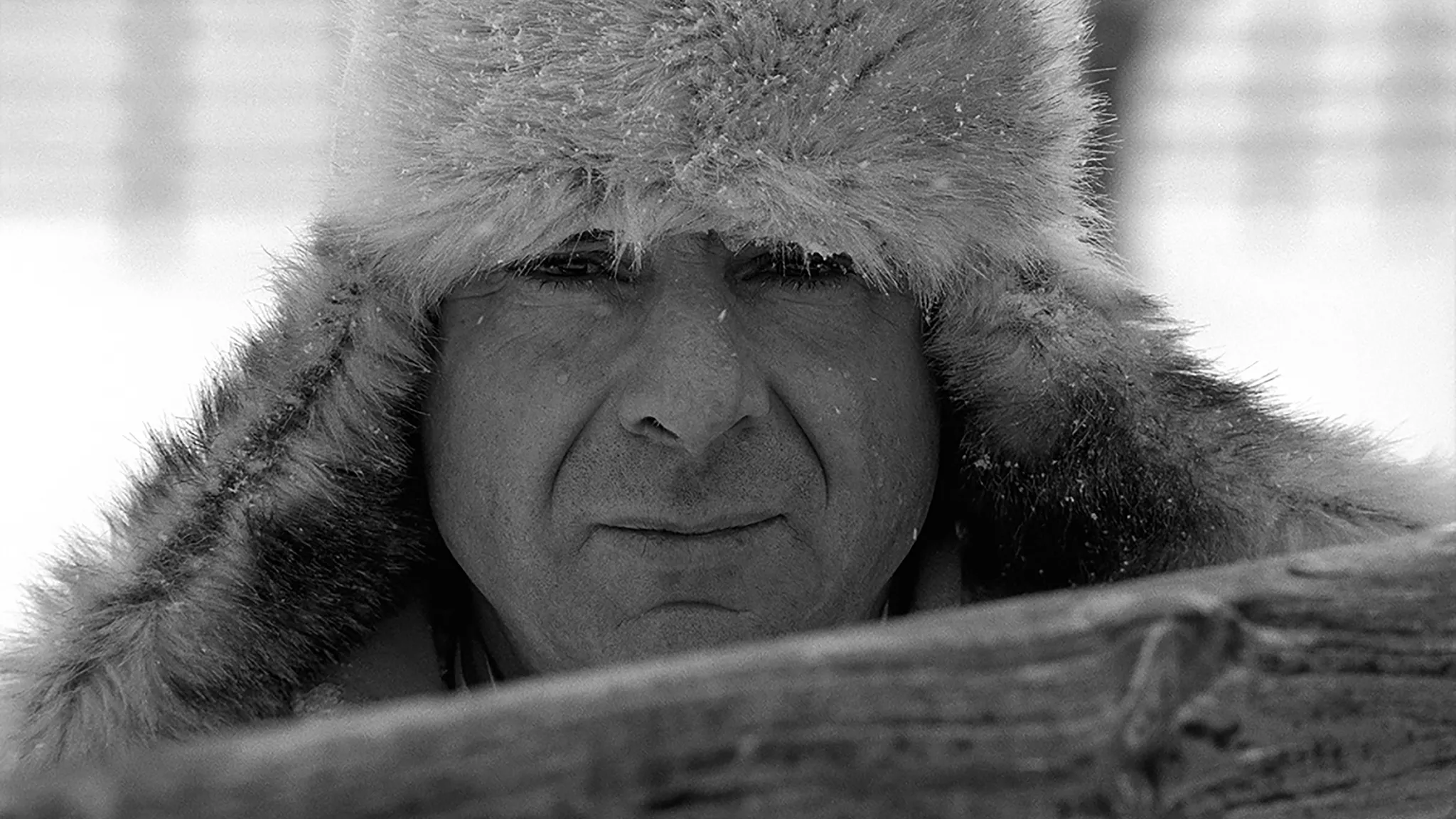

Roman Polanski on the set of Repulsion, London, 1964![Vilmos Zsigmond during the filming of <i>Sweet Revenge</i>, Tacoma, Washington, 1975]() Vilmos Zsigmond during the filming of Sweet Revenge, Tacoma, Washington, 1975

Vilmos Zsigmond during the filming of Sweet Revenge, Tacoma, Washington, 1975

This is a photo of the great production designer Alexandre Trauner, who worked on Reunion. That was his 100th film. He died not long after.

This was one of his last films. He was such a wonderful production designer. Anything I’d ask him to do, he’d do.

It’s amazing to think you worked with somebody who worked on Children of Paradise, Rififi and The Apartment. You also worked on Reunion with Harold Pinter, who wrote the screenplay.

That was a complete and wonderful surprise. One of the producers gave it to Pinter’s people to read. I said, “What, are you crazy? We’ll never get him!” But he loved it. I sat down with him for an hour and we had a great time. He really was a delight, and we became great friends. And he wrote the script.

You’ve worked with some of the greatest cinematographers of the last 50 years. It’s an extraordinary list. I mean, who didn’t you work with? You worked with Adam Holender for Puzzle, Panic, The Seduction of Joe Tynan and Street Smart. Vilmos Zsigmond on Scarecrow, Sweet Revenge and No Small Affair. Bruno de Keyzer on Reunion and The Day the Ponies Come Back. Robby Müller, who worked with Wim Wenders, on Honeysuckle Rose. And Pasqualino De Santis, who was Visconti’s cinematographer, on Misunderstood.

They all spoke with serious accents.

They’re all European.

There were great American cinematographers too, but they were always booked, so I had to go elsewhere. All the guys I worked with would speak their mind. If they didn’t like something, they’d want to talk about it. And they all had good taste.

For someone like Adam Holender, Puzzle and Panic are two such different aesthetics.

Adam had done an American film before that one, Midnight Cowboy, with John Schlesinger. But Adam was friends with Roman [Polanski], and it was Roman who introduced us. Adam and I became great friends. And we still are. We still have lunch occasionally.

His artistic sensibility is grounded in genuine technical sophistication. That comes from the Łódź Film School background that he and Polanski shared. They were unbelievable technicians. Polanski could look at a room and tell you the size of the lens you would need to create a certain shot. Adam as well.

Adam knew his photography. Adam and I would have long talks about what we’re looking for, and you could take scenes from those two films and put them in European films easily. Though you’re right, they do have different aesthetics.

Puzzle is about the fashion world, and Panic is the anti-fashion world.

Yes, but I’m still the director, and I like to think I know something about images.