Movie Poster Mavericks

By DK Nnuro

Jaws by Leonardo, 2021

Movie Poster Mavericks

DK Nnuro

The hand-painted film ads from Ghana that became a fantastical art form

October 25, 2024

Many moviegoers first encountered the 1993 Robin Williams comedy, Mrs. Doubtfire, via its iconic movie poster that introduced the eponymous nanny as a plump, matronly figure captured from behind, her head cheekily concealed by a large umbrella to add a touch of mystery to Williams’s drag transformation. Now consider the poster’s Ghanaian corollary, created two decades later in 2014: Mrs. Doubtfire smirks as she gouges out a young man’s eye with a witch’s broom, the blood running down his chest.

It went viral, making this Mrs. Doubtfire rendition one of the most recognizable examples of Ghana’s hand-painted movie posters. These wild artworks emerged in the mid-1980s as the advertising product of an underground industry known as Ghanaian Mobile Cinema. In keeping with the Ghanaian film industry’s direct-to-video turn and the ubiquity of VHS tapes of Hollywood and Bollywood blockbusters, the clubs were traveling operations that sprung up in the coastal regions, with more permanent theaters emerging in cities like Accra, Cape Coast and Kumasi. To be in business, a traveling club operator required a truck, into which they loaded a diesel generator, a VCR, and a TV or projector. Operators set up makeshift indoor and outdoor theaters when they toured rural sections of the country. For a fee, locals—often gathered in a public square, sometimes sitting on white plastic chairs they’d brought with them—were treated to a wide variety of films made in Ghana and abroad.

One truth about the movie business: Just because you build it doesn’t mean they will come. You must gin up excitement among a prospective audience. In the West, of course, with its well-oiled publicity machines, this pre-release enthusiasm has been achieved primarily through trailers and posters. Because club owners in Ghana didn’t have access to such mass media for either local or foreign films—and couldn’t print their own posters due to the military government’s restrictions on the import of printing presses—they commissioned local artists to make hand-painted advertisements. Artists would screen the films—or sometimes simply receive a plot summary—and then, working in oils, paint posters on large flour sacks (often 40 to 50 inches in width and 55 to 70 inches in height) that spotlighted the characters and themes. These original works were signed by the artists, with names like D.A. Jasper, Joe Mensah and Leonardo becoming well recognized regionally for their idiosyncratic handling of the sensational material. Their work evinced some of their own respective fascinations and obsessions—from martial arts and soccer to reggae music and the Bible.

But that isn’t to say the posters were entirely zones of free expression. Just as American advertising minds bet on Mary Poppins nostalgia to induce a sense of wholesomeness that would appeal to a wide audience, in Ghana, club owners put their money on the country’s preoccupation with Christian teaching and, in addition to following the market (starting in the 1980s, the most popular mass-produced films were horror movies with Christian themes), encouraged artists to create posters that emphasized evil’s grotesqueness and the inevitability of its downfall. Despite the omnipresence of Christian teachings, film club operators also screened more mainstream fare, including horror, action and romances imported from abroad. The ads for these films usually had an extra bite to appeal to its intended target: Horror movies were depicted as even more horrific, action as more brutal, and romances as even more carnal.

Ghanaian hand-painted movie posters reached their peak in the ’80s and ’90s. By the turn of the 21st century, they had largely gone the way of the video clubs, which were made obsolete by the accessibility of home viewing technology. But thanks in part to the publication of two volumes of Extreme Canvas: Hand-Painted Movie Posters from Ghana, edited by the Los Angeles–based African art scholar and gallerist Ernie Wolfe III, these posters have found new life in the global art market. Today they are prized by art collectors and can be found in museums and galleries around the world, including the Chicago-based Deadly Prey, which reps many of Ghana’s most prolific poster artists. The frenzy is such that buyers are now commissioning them for original works. With this new market, artists like Leonardo, creator of the gruesome 2014 Mrs. Doubtfire poster, continue to keep the art form alive without abandoning the goriness, luridness and extreme license-taking on even the most fantastic movie storylines.

All artworks commissioned by Deadly Prey Gallery, based in Chicago.

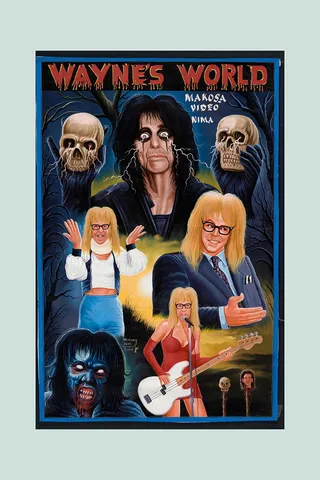

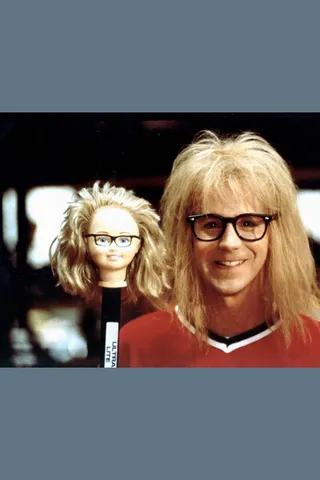

Wayne’s World, dir. Penelope Spheeris, 1992

Mr. Nana Agyq. Wayne’s World, 2020. Oil-and-enamel mix on recycled flour sacks, 39 in. by 59 in. Private Collection.

Fitting that shock-rocker Alice Cooper is front and center in this poster by the Kumasi-born artist Mr. Nana Agyq. Despite his small cameo playing himself in the 1992 film that stars Mike Myers (Wayne) and Dana Carvey (Garth, triply iterated here), Cooper has spent a lifetime embodying the governing aesthetic of Ghana’s hand-painted posters: gore.

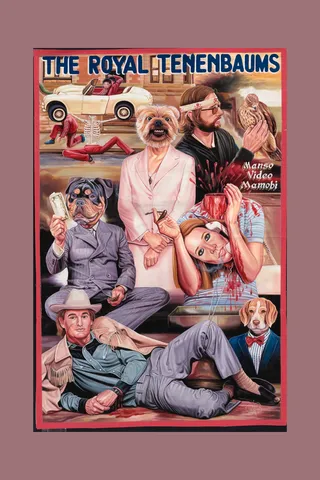

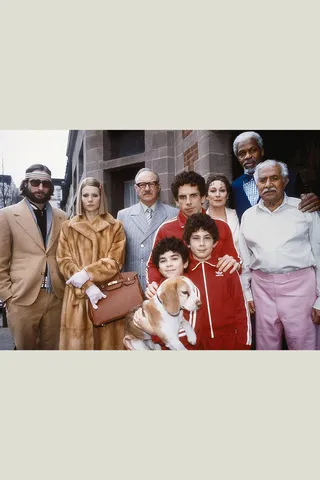

The Royal Tenenbaums, dir. Wes Anderson, 2001

C.A. Wisely. The Royal Tenenbaums, 2021. Oil-and-enamel mix on recycled flour sacks, 41 in. by 60 in.

“Does Wes Anderson Hate Dogs?” ran the headline of a 2012 New Yorker send-up of the filmmaker’s oeuvre. Anderson surely does not, but one of the article’s chief justifications is the scene at the end of 2001’s The Royal Tenenbaums, where the family beagle, Buckley, is a car crash’s only casualty. Accra-based artist C.A. Wisely wryly calls that grisly event to mind with his dog people flanked by bloodshed.

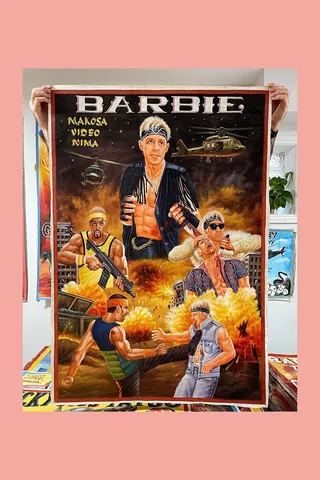

Barbie, dir. Greta Gerwig, 2023

Mr. Nana Agyq. Barbie, 2023. Oil-and-enamel mix on recycled flour sack, 33 in. by 47 in.

This rendition of Barbie by the artist Mr. Nana Agyq—full of murder, street fighting, explosions, Army helicopters and urban violence—couldn’t be further from director Greta Gerwig’s cheerful, female-centered rendition of the iconic doll’s cinematic universe but speaks to the creative leanings of its artist, whose favorite genre to depict is horror. Here, Ken lives out all his secret campy, macho, blood-and-guts fantasies—more G.I. Joe off-duty than Barbie. Perhaps a peek at one idea for a widely hoped-for sequel?

“Their work evinced some of their own respective fascinations and obsessions—from martial arts and soccer to reggae music and the Bible.”

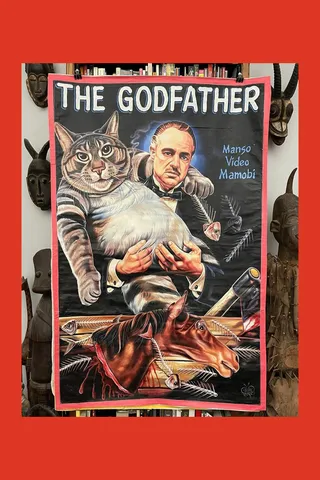

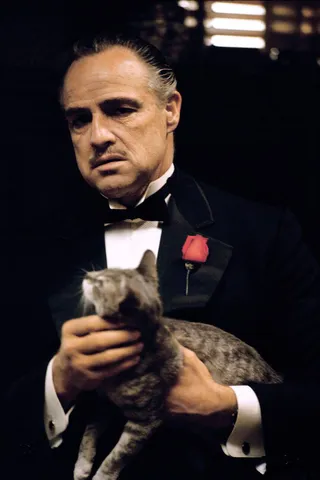

The Godfather, dir. Francis Ford Coppola, 1972

C.A. Wisely. The Godfather, 2021. Oil-and-enamel mix on recycled flour sacks, 40 in. by 60 in.

Arguably the most memorable moment in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1972 classic, The Godfather, is the horse-head revenge scene. It has baked-in blood and gore—a man wakes up to find his horse’s decapitated head in his bed—and thus is a perfect candidate for the Ghanaian movie-poster treatment. But C.A. Wisely, who began as an apprentice to fellow Ghanaian poster artist Heavy J, does not stop there with the animal references. Wisely doesn’t just invoke the gray street cat that Don Vito Corleone is seen petting behind his desk—he turns him into a stone-faced fat cat worthy of a Mafia don.

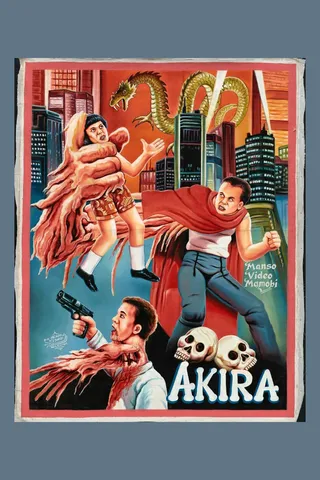

Akira, dir. Katsuhiro Ôtomo, 1988

Heavy J. Akira, 2021. Oil-and-enamel mix on recycled flour sack, 31 in. by 42 in. Private Collection.

Manga, Japan’s popular graphic-novel genre, is not without its own depictions of violence. Akira (1988), based on a manga series, is packed with explosive action of the futuristic-cyberpunk variety. The artist Heavy J, who got his start painting posters for the Bombay Video Club while still a teenager, goes in the very opposite direction for his poster, reveling in the more analog horror of dragons, skulls, and choking, tendon-flayed hands.

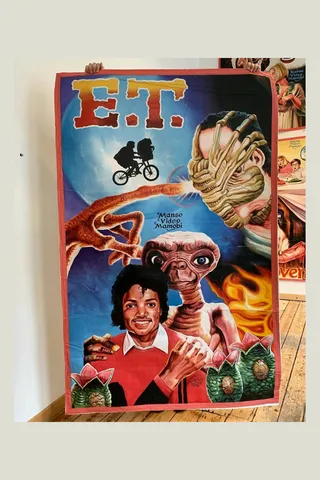

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, dir. Steven Spielberg, 1982

Heavy J. E.T., 2018. Oil-and-enamel mix on recycled flour sacks, 40 in. by 60 in. Private Collection.

Steven Spielberg’s strange but certifiably sweet rendition of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial hardly meets the gruesome standard of Ghanaian movie posters. Heavy J takes inspiration from more horror-drenched extraterrestrial fare by adding in imagery more in keeping with the Alien franchise. And speaking of otherworldly—how about that cameo from Michael Jackson, who doesn’t appear in the film?

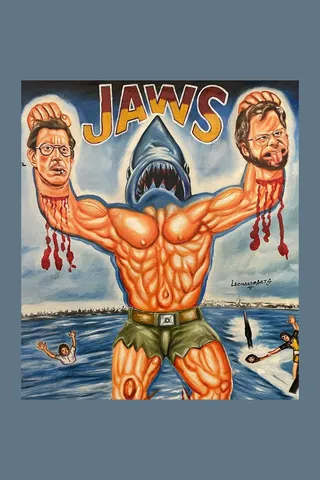

Jaws, dir. Steven Spielberg, 1975

Leonardo. Jaws, 2021. Oil-and-enamel mix on recycled flour sacks, 41 in. by 59 in.

Decapitation is the lingua franca of Ghana’s hand-painted movie posters. Steven Spielberg’s 1975 classic Jaws is plenty gory, but even a human-chomping great white doesn’t instill enough fear and reverence, so Accra-born artist Leonardo reimagines the film’s beast in pure male-muscled glory, flaunting his strength as if it were Arnold Schwarzenegger in the water and not Spielberg’s elusive mechanical shark.

“The frenzy is such that buyers are now commissioning for original works.”

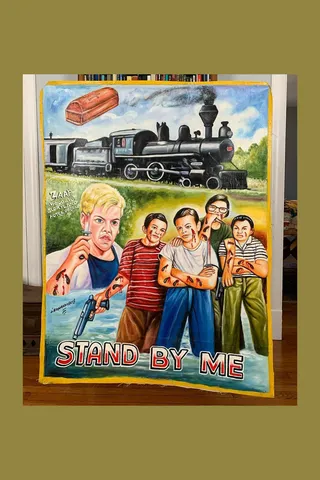

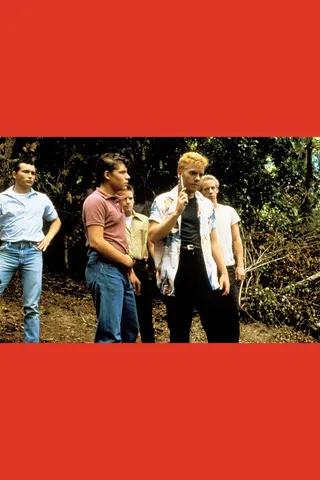

Stand by Me, dir. Rob Reiner, 1986

Leonardo. Stand by Me, 2019. Oil-and-enamel mix on recycled flour sacks, 40 in. by 56 in.

A moving 1986 coming-of-age film about four boys on a quest to find the dead body of a missing kid does feature one scene with leeches. Which is just enough to make them the main focus of Leonardo’s portrait of the friends—now rendered more like a street gang—as they square off against a knife-wielding psycho and a speeding train. Self-taught virtuoso Leonardo—who created work for Ghana’s underground video clubs—introduces a moment of reverence with the inclusion of a coffin floating miraculously in the clouds.

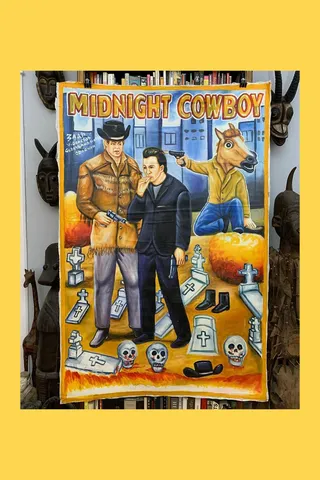

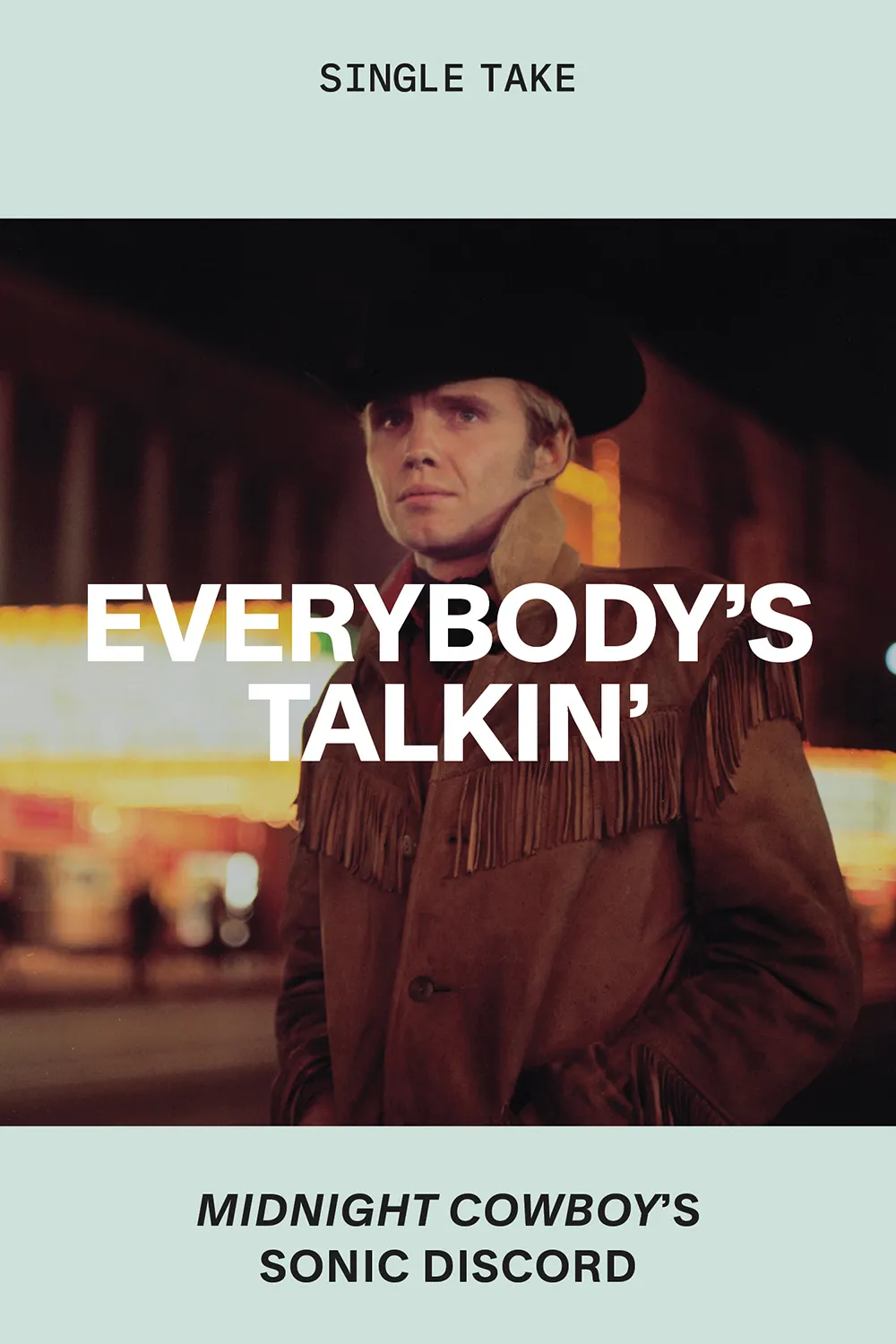

Midnight Cowboy, dir. John Schlesinger, 1969

Leonardo. Midnight Cowboy, 2020. Oil-and-enamel mix on recycled flour sacks, 41 in. by 60 in.

Midnight Cowboy (1969), a film about the unlikely bond between a male prostitute and a con man, is unflinching in its depiction of seedy underworlds. Hand-painted poster pioneer Leonardo, a prolific artist who died in 2023, employs maximal poetic license to capture those dire straights, rendering the two main characters in a skull-ridden graveyard (a hint of the dangers of sex work, or a more intentional reference to the death at the end of the film?) while the “cowboy’s” re-created horse now aims a revolver at them—a rather loaded image indeed.

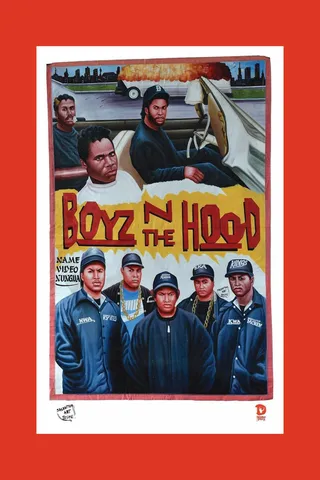

Boyz n the Hood, dir. John Singleton, 1991

Salvation. Boyz n the Hood, 2018. Oil-and-enamel mix on recycled flour sacks, 41 in. by 60 in.

Released in 1991, the South Central L.A. drama Boyz n the Hood catapulted its stars to fame—among them Ice Cube, who was already a member of the hip-hop group N.W.A. Viewers at the time speculated that Ice Cube’s hard-edged portrayal of Doughboy was an extension of his gangsta-rapping reputation. Accra-born artist Salvation (who apprenticed with Ghana poster legends Joe Mensah and Heavy J) makes that speculation concrete, dividing his flour-sack canvas in half: the top panel devoted to a still from the film and the bottom panel a tribute to the notorious Compton-based group.