Object Lesson

By Heidi Julavits

Summer Hours, dir. Olivier Assayas, 2008

Object Lesson

How director Olivier Assayas uses totems—from antique vases to latex catsuits—to provoke primal questions about ownership and identity

By Heidi Julavits

July 1, 2024

Things things things things things things things. My friend, a man easily distressed by material clutter, can be heard in overwhelmed times mumbling, “life is nothing but object management.”

Two standout films by the French director Olivier Assayas might be categorized as “object management cinema.” Objects cause problems and stress. They test loyalties and become obligations. They contain stories and identities—their own, and others’. They can even objectify the humans who interact with them. Objects are excellent metaphors, and in Assayas’s work, they are also excellent characters. They exist, and therefore have a history, a dramatic arc, a fate. When people die, their abandoned objects do battle with the living, as they try to profit off the stories those objects might tell.

![]()

Charles Berling in Summer Hours

![]()

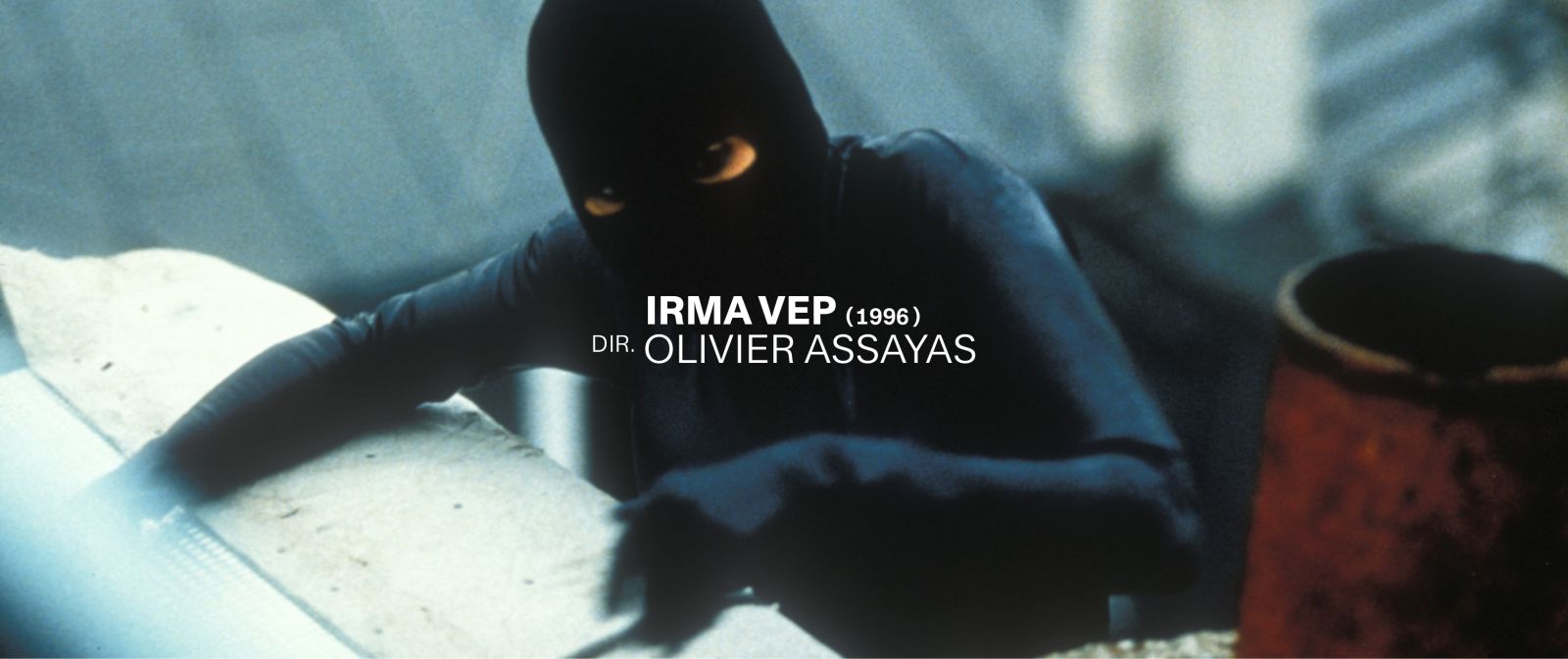

Maggie Cheung in Irma Vep

Assayas made Summer Hours (2008), about a family’s inheritance drama following the death of a matriarch, soon after his own mother died. While the movie explores a wide range of feelings and ideas—grief, muses, the dehumanizing burden of sustaining a male artistic legacy, the airlessness (and decline) of French culture—it is also, on a simplified level, a story of two vases.

Hélène Marly (Edith Scob) lives in a French country house once owned by her uncle, Paul Berthier, a dead post-Impressionist painter of average note in France, and unknown to the rest of the world. Summer Hours opens at Hélène’s 75th birthday party. She’s surrounded by family—a daughter, Adrienne (Juliette Binoche); her two sons, Frédéric (Charles Berling) and Jérémie (Jérémie Renier), with their partners and children in tow—as well as that brand of bohemian disorder and decrepitude that signifies multigenerational wealth. A person cannot buy this world. It can only accrue, over decades, like the dust on Berthier’s rare Louis Majorelle desk or his Josef Hoffmann credenza.

At the birthday party, Hélène’s children give her a cordless telephone with multiple handsets and molded-plastic charging stations. She’s clearly displeased and even offended by this object she cannot (or will not) understand how to operate. While the gift gestures toward connection and care, it also suggests that her children will not be worthy inheritors, or preservationists, of the stopped-in-time house and its curated, Paul-era belongings. The two younger children live in America and China, working for companies that mass-produce accessories and sneakers. They aren’t keepers of the family flame—or the national one, either. Given their lives and careers, neither intends to spend much future time in France.

Fortunately, Hélène has forecast their unworthiness. She’s already planned the futures of Berthier’s most valuable objects. But two items in his estate escape her notice: a pair of vases.

Before making a film about his mother’s death, Assayas made a film about a woman who would go on to briefly become his wife. If the movie about his mother is the story of two vases, 1996’s mega-meta-drama Irma Vep, Assayas’s artistic-process disaster movie, is the story of a latex catsuit.

René Vidal, a once famous, now irrelevant film director (played by Jean-Pierre Léaud), attempts to revive his career by remaking a 1915 French silent classic, Les Vampires. According to the scathing critique offered by one journalist, Vidal contributed to the current sorry state of French cinema by extending, beyond its expiry date, the auteur movement, which the journalist finds indulgent, disrespectful of audiences’ time and attention, all about gazing at le nombril.

From the start Les Vampires’ production is cursed by disarray. Vidal is a mercurial, demanding boss. The workplace is toxic; crew members blame and backstab. Vidal, however, decides to take license with the title role. Instead of a French actress, he casts Hong Kong cinema star Maggie Cheung as Irma Vep, the protagonist of Les Vampires. Irma Vep is a spooky, hypnotic ringleader of a Parisian criminal underground collective, a cat burglar who springs from roof to roof. Cheung, at this point in her career, had become a star after her appearance in the 1985 Jackie Chan action movie Police Story. In 1988 she starred in Wong Kar-wai’s first film, As Tears Go By, the first of many movies the two would make together.

Trickily, however, or dizzyingly, Assayas casts Cheung to play herself—or, rather, a fictional version of herself (or not?)—i.e., a movie star from Hong Kong hired by an increasingly out-of-touch French director trying to infuse his inert work with a splash of global modernity.

“I have this idea of you,” Vidal tells Cheung, which might equally have been Assayas’s idea, “in this part, in this costume. I thought it was very exciting.”

The production flags. Vidal quickly loses his passion for the remake. Cheung, the cultural outsider, is the only character in Irma Vep able to forthrightly, rather than sycophantically, interact with Vidal in his increasingly addled despair. (At one point the cops are called to his house because he’s had a violent fight with his wife.)

“If the movie about his mother is the story of two vases, 1996’s mega-meta-drama Irma Vep, Assayas’s artistic-process disaster movie, is the story of a latex catsuit.”

“Irma’s no flesh, no blood,” he tells Cheung, just after being tranquilized by a doctor. “She’s just an idea. How can I be interested in an idea?”

“In the end,” he says, in what might read as both a compliment and an insult (to Cheung, to action movies, to directors like him who fetishize and endlessly loot France’s cultural past for inspiration), “there is nothing for you to act. Irma is an object.”

Hélène’s much-celebrated vigor at her birthday party might suggest to savvy viewers that she won’t be alive much longer, and she isn’t. She’s dead by the second scene. Her children, by a two to one vote, decide to sell the house and liquidate its contents. The majority siblings, Adrienne and Jérémie, given that they live abroad, won’t, in their words, “benefit” from the house as a possession or a museum to their dead great uncle. Its only benefit is as an asset. They need the cash.

The house and its belongings are thus evaluated by professionals at buying and selling ancestral merchandise. Berthier, one curator observes approvingly while assessing his collection, had “a remarkably interesting collection of art nouveau furniture.”

He also had an eye for his niece, Hélène. A charged illicitness infuses the dim, messy rooms that Hélène maintained as a shrine. She spent her adult life promoting her uncle’s legacy internationally; she succeeded, just before her death, in publishing a book, in English, about his work. It’s clear to everyone but her elder son, Frédéric, that she and her uncle were fucking.

“She was Paul’s last great passion,” declares the family’s longtime friend and president of the Musée d’Orsay.

But what was valuable in the past isn’t any longer. Two paintings by Camille Corot, understood by the majority siblings as the most secure source of funds (the sole dissenter, Frédéric, genuinely loves the Corots, and is pained to sell them), are met with less enthusiasm by the family’s executor. “His value on the international market is hard to call,” he says. “And his work is austere.”

Les Vampires publicity photo, 1915

The assessor, however, finds a pair of overlooked 19th-century glass vases stored in a cabinet, and these, it seems, are valuable, made by Félix Bracquemond. They possess an adorable creature-ness. One looks like a smoky glass penguin with four feet; the other is covered in green glass bubbles and has the silhouette of a fish. The elder son asks his mother’s cherished, longtime housekeeper, Éloïse, if she would like to choose a souvenir, and when she chooses something, to her eye, worthless—the vase with the green glass bubbles—he lets her take it. For Hélène, empty vases were like death. Éloïse totters down the shaded driveway with the vase tucked precariously beneath her arm.

Zoé, Les Vampires’ costume designer (played by Nathalie Richard), finds Cheung’s burglar costume in a sex shop. The shiny, clingy latex catsuit (which is paired with a hood that reveals only her eyes), Zoé observes, makes Cheung look like “a plastic toy.” Zoé and her coworkers gossip about how enthralling and sexy Cheung is, both in and out of the catsuit. Zoé tries to sleep with her. Cheung is a source of deep fascination, an object to behold, even to worship. She is treated like the Majorelle desk, a curatorial find to gawp over and try, inappropriately, to touch.

Cheung, meanwhile, remains coolly professional, curious, warm, intellectually grounded. By contrast, her French coworkers appear clownish and flitty, remnants of French cultural domination so far in the past that caricature is their only remaining option. Zoé and the rest of the cast and crew are characters in a satirical workplace caper, while Cheung’s character stars in a visionary cultural critique.

Which does not mean Cheung is immune to the allure of black latex and her catsuit’s compelling, transformational power. After the talk with Vidal, Cheung returns to her hotel, puts on the catsuit, prowls the halls, sneaks into a guest’s room, steals a jeweled necklace and falls into an impenetrable slumber, missing her morning call time. When tightly encased in what looks like black gum, she might to some, like Zoé, be reduced to a toy. Yet while Cheung is the cat burglar of objectification (as a woman, as the sole Asian person), she steals its power for herself. Her vision is the more original and expansive. Irma Vep is neither idea nor object. She creates, in her off hours, the movie that Vidal cannot. She rejects his limited view of art, and of her.

“You think you are at the core of the scene,” the despondent Vidal says, “but in fact you are just on the surface.”

Cheung responds: “But if you feel it, you’re inside, you’re not on the surface.”

The vases’ journeys diverge. Two opposing fates befall them. Which is the preferred? The movie makes it clear. The one with green glass bubbles goes home under the arm of Éloïse. She’s elderly herself and lives a solitary life in an apartment. For a short time, this vase will be cherished by her, both for its utility and its personal meaning, after which its fate is unknown.

The one that looks like a penguin goes to the Musée d’Orsay. At the end of the film, Frédéric and his wife visit the museum. They view the desk and the vase in cultural captivity. Museumgoers’ attention skitters over the furniture and objects; they answer their cell phones and rush through the exhibits. Frédéric observes that the objects, which were once in their uncle’s house, touched and used, look “caged.” The vase is kept in a vitrine with other vases, all deemed too valuable to fulfill their original purpose. None will be filled with flowers again.

The fate of the Les Vampires reboot is also unknown. Irma Vep ends as the new director takes over (Vidal is hospitalized). He replaces Cheung with a white Frenchwoman; he’s offended that “La Chinoise” should star in the remake of a classic French film. Whatever newness might be discovered in this old artifact is retracted. Homage, in the new director’s eyes, is only paid through strict replication.

![]()

Jérémie Renier, Juliette Binoche and Charles Berling in Summer Hours

![]()

Edith Scob in Summer Hours

If there’s a scene where Cheung is fired, we don’t see it. In the scene’s absence, it feels as if she grew bored of the inbred smallness of the French movie scene and cat-burgled herself out of both films. Her absence inspires hushed, awed speculation. The crew members disagree about where she’s headed. To New York? To Los Angeles? She’s rumored to be meeting with director Ridley Scott, says one. She’s so far out of their league that they speak of her breathlessly. She’s engaged in a global cultural economy that they can’t even aspire to join.

Both Summer House and Irma Vep pose questions about ownership—of things, of stories, of French identity. What is a trap? What is an exciting opportunity to remake or start over? “It’s completely different,” Cheung says, trying to talk Vidal out of his self-pitying funk. “We’re doing something different. It’s 1996.”

But Vidal can’t see it. “It’s just images about images. It’s worthless.”

Following the release of Irma Vep—which became Assayas’s first international hit—Cheung and Assayas became a famous cineast couple, marrying in 1998 and divorcing in 2001. Assayas’s reputation as a filmmaker was not so much saved (unlike Vidal, he was on the incline) as elevated. Yet the whole film has a riddling twistiness to it that extends decades beyond the run time. Irma Vep is an anagram of vampire. In 2020, when Assayas decided to remake Irma Vep in the style of the original Irma Vep’s remaking of Les Vampires (i.e., this Irma Vep miniseries is a remake of a movie called Irma Vep, which is about a remake of a movie called Les Vampires), it’s difficult not to perceive a slightly vampiric relationship between Vidal and his star, and Assayas and his once star, now former wife.

Cheung had vanished so completely from Assayas’s life that when he tried to get her permission to use her identity again, as the 2020 version of her 1996 character (as an actress who, in Irma Vep 1.0, almost starred in a movie called Les Vampires), he didn’t know how to contact her. The only email address he had for her was defunct. Eventually, when she read the script, she didn’t think that naming the character “Maggie” made much sense. (Cheung retired from acting in 2013.)

Assayas respected her wishes. “Maggie” is replaced, but not entirely. The new character, Jade Lee, has the same bio—she’s the Hong Kong actress hired to play Irma Vep in Irma Vep, who then married the movie’s director. Lee returns, wraithlike, to visit (or haunt) Vidal as he tries again, more than two decades later, to remake the same French classic once again.

At the end of Summer Hours, the fate of the house is unknown, too. Who has bought it? What is their vision for its future use? Days before the deed transfer, Frédéric’s teenage children throw a party. Their friends smoke, drink, dance, swim in the pond. The house, empty now and uninhabited, is arguably, finally, a utilitarian, alive space, meant to do more than store the past. In the final scene, Frédéric’s daughter experiences a fleeting moment of sadness when she tells her boyfriend, “My grandmother said that one day I’d bring my children here, when I had kids.” But her nostalgia for what could have been quickly dissipates. The new, unweighted future awaits.