Oh, Make Me Over

By Sloane Crosley

Clueless, dir. Amy Heckerling, 1995

Oh, Make Me Over

Sloane crosley

The not-always-pretty evolution of the makeover movie

September 13, 2024

AUTHOR READS

![]()

Mean Girls, dir. Mark Waters, 2004

![]()

Legally Blonde, dir. Robert Luketic, 2001

Legally Blonde (2001) can’t be the only example, can it? Can it be the lone major film so far in this century in which a stereotypically “hot” woman undergoes a transformation that makes her less stereotypically hot? Legally Blonde is a film in which the glasses go on, not off, in which the pastel bunny ears are swapped for a knit cap. So long, California bikini. Welcome, Massachusetts layers. When Elle Woods (Reese Witherspoon) comes to the realization that, despite having been admitted to Harvard Law School, she is “never going to be good enough” for her ex-boyfriend, she spins around on her heel. And not into the arms of a teaching assistant (Luke Wilson), but first and foremost toward herself. “I’ll show you how valuable Elle Woods can be,” she mutters. As viewers, we understand the “you” to be not any particular human, but the whole world. If this woman has a true love interest, it’s criminal law! Yet, she still gets her hair styled and wears an egregious amount of pink, power suit included. She never sacrifices her individuality in order to be perceived in a more elevated manner.

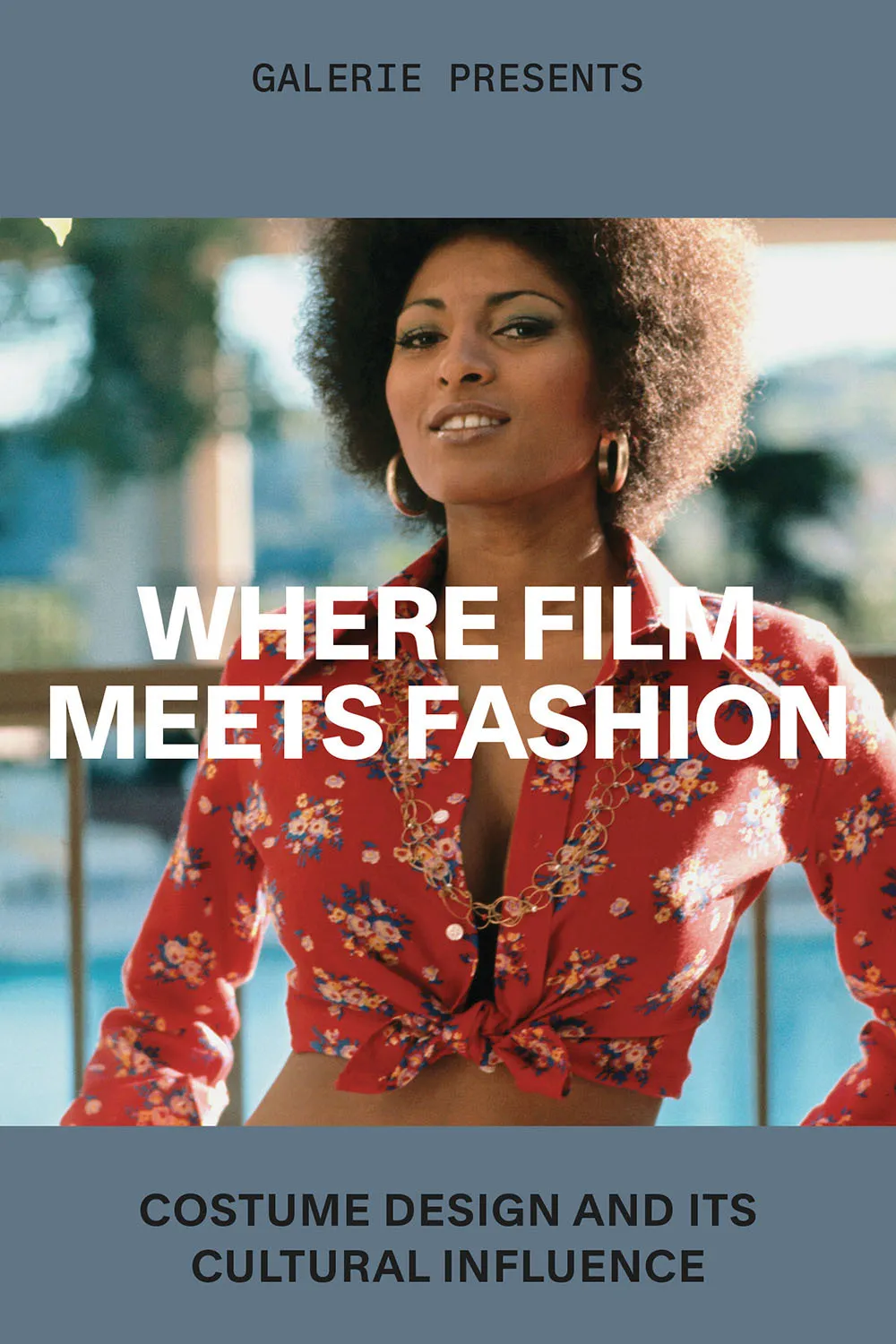

Legally Blonde is indeed an anomaly in the makeover movie genre, that stickiest of comedy wickets. Here is an entire brand of cinema in which a young woman is made to understand she’s far more beautiful than all that drab clothing and lack of concealer would indicate, a realization achieved with the help of a straight man or chicer girlfriend, one who proceeds to refashion our heroine using the prevailing beauty standards of the day. Finally, her internal merit can be reflected on the surface. Phew. There’s often a bet involved, an overlay of ego (I can make any woman a prom queen!) and capitalism (it’s the 1980s and we have healthy allowances!). It’s a genre as old as “Cinderella.” Except “Cinderella” isn’t a comedy. Which prompts the question: What, exactly, are we laughing at?

![]()

The Devil Wears Prada, dir. David Frankel, 2006

![]()

My Fair Lady, dir. George Cukor, 1964

We love a good makeover movie. Are they superficial? Mostly. Are they a guilty pleasure? Totally. To our vague credit, we were indoctrinated to love them. All one has to do is consult the nearest child and that child will tell you the ugly duckling becomes a swan, not the other way around. Swans are widely considered to be more graceful and refined birds, even though they’re notorious assholes who will kick other birds out of their nests. Still, the shadow lesson of that particular fairy tale (and of “Cinderella,” for that matter) is that beautiful people belong together. As for the nonswans? Well, they belong together too. But the story ain’t called “The Decent-Looking Duckling.”

This fantasy, that any woman can walk through a revolving door and come out transformed into a classical beauty, should be a joke, but it’s now moved beyond a Hollywood screenwriting staple into real life via influencer culture. On Instagram and TikTok, makeover videos and tutorials run rampant (behold the makeup sponge, meant to create an instant Photoshop effect from foundation). Some of these videos feature celebrities, but most don’t, which is precisely why they’re so effective (a swan turning into a glitzier swan? Bor-ing). They’re even edited like makeover-movie montages, with upbeat soundtracks, professional-grade lighting and hours of blending condensed into seconds. TikTok, in particular, is home to the finger-snap, the twirl and boom: Goodbye, sweatpants, it’s prom-dress time.

“Who among us has not fantasized about the moment when those who have underestimated us are stopped in their tracks?”

Pull the string and you’ll see all those “Get ready with me!” videos are part of a long tradition of onscreen makeovers. The classic 1948 musical Easter Parade opens with Don Hewes (Fred Astaire), abandoned by his partner and determined to make a star out of the next dancer he spots during a floor show. As part of this one-man training program, he informs Hannah Brown (Judy Garland), “There is no more Hannah Brown. From now on, you’re Juanita.” It’s the sort of declaration that would never fly today. But it’s something of a relief to hear the truth of the makeover plot uttered out loud. You can’t change people. Just ask your therapist. And you really can’t change Hannah Brown (a dancer afflicted with left/right confusion). But the fantasy that you could change another person, and quickly, that there are those with the capacity to transform us and those of us with the capacity to be transformed, is in alignment with an old-timey movie musical. Especially one with so many wide-brim hats. Don even buys Hannah a wardrobe similar to that of his original partner (this stunning sartorial quick-change is itself a staple of the genre: think 1990’s Pretty Woman, in which sex worker Julia Roberts sashays through the stores of Beverly Hills, armed with Richard Gere’s credit card). Eventually, Don realizes he just can’t fight city hall. “From now on,” he informs Hannah, “you’re going to be yourself.” Nota bene: This movie is over 75 years old; it’s his realization, not hers.

My Fair Lady (1964) is yet another makeover musical, and a personal favorite in the style and comedy departments. It’s also one we won’t see the likes of again. After referring to Eliza Doolittle (Audrey Hepburn) as a “draggle-tailed guttersnipe,” Henry Higgins (Rex Harrison) decides to run a six-month experiment to transform this unwashed commoner into a bejeweled, ball-gown-clad duchess (one reason makeover movies are so ludicrous is that these bets are being placed on actresses who don’t appear to have much of a journey in front of them). My Fair Lady, despite being the urtext of these films is, ironically, almost too much of a makeover movie to qualify as one. The metamorphosis is so extreme, with Hepburn’s now-perfect posture, style and elocution, it’s more Frankenstein than “Cinderella.” But it gets away with so completely turning Eliza into a duchess because it has the oldest plot of them all: My Fair Lady is based on the George Bernard Shaw play Pygmalion, the title itself a nod to the classic example from Greek mythology of a male artist falling in love with his female creation. In the final scene of the film, Eliza puts her former accent on, almost as a party trick, as if to say, “I can do this for a bit of flavor, but why would I?” She’s become a proper lady, through and through. Her raggedy former self is just that: former.

But are all these reinvention plots so nefarious? Not compared to some of the other narratives (like the marriage plot or the revenge fantasy) that women have to either accept or reject in cinema. We gravitate toward makeover movies because of their uncomplicated nature and their naked superficiality. Because, in spite of their wonky messaging, they make us laugh at ourselves. Even as we feel superior to their pat lessons, we know superiority can be a form of enjoyment, too.

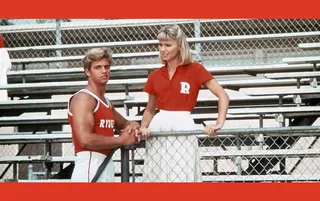

These films promise transformation in three hours or less. And they suggest that magic is not only real but accessible. The magic wand is called a “pore strip” and it’s available at your local drugstore for about $8.50. Plus, despite their formulaic nature, makeover movies retain a sense of suspense. How different will our heroine look and what will that difference give her? Moreover, what will she do with this newly acquired power? This suspense is in the core of the enterprise, in that slow-motion walk down the stairs (Rachael Leigh Cook’s presto-chango via a red minidress in 1999’s She’s All That) or out of an airplane hangar (Sandra Bullock wearing a bandage dress in 2000’s Miss Congeniality) or across the offices of Runway magazine (Anne Hathaway in 2006’s The Devil Wears Prada complete in a couture blazer and thigh-high boots). The former two examples literally fail to stick the landing. Our heroines trip. Looks like their clumsy selves are still in there! They are hardly Sandy (Olivia Newton-John) in Grease (1978), slathered in black leather and ungodly amounts of confidence as the reinvented pin-up. Though perhaps that’s a net positive. It’s one thing to get a haircut and a facial, and something else to go from frigid good girl to sexpot for the sake of fitting in.

During all these films, Grease included, the audience gazes upon and judges the other dumbstruck characters (always filmed with their mouths agape) when The Big Reveal happens. This is meant to flatter our instincts. It’s as if we’re right there in detention, in the school library of The Breakfast Club (1985), after the wealthy Claire Standish (Molly Ringwald) applies makeup and a hair bow to “basket case” Allison Reynolds (Ally Sheedy). We think: “That’s right, boys, she’s stunning! Rue the days when you neglected to be stunned!” It taps into a primal teenage desire: Who among us has not fantasized about the moment when those who have underestimated us are stopped in their tracks? Never mind the fact that any semi-sane adult would prefer this awe to be the result of an achievement, like a fellowship or a job promotion. And never mind that when Claire tells Allison, her guinea pig, “You really do look a lot better without all that black shit on your eyes,” she’s wrong. She does not look “a lot better.” She just looks less like herself.

The more contemporary the makeover movie, the more this premise is softened by a character’s return to her original form. By the end of Mean Girls (2004), Cady Heron (Lindsay Lohan) has reverted to a mathlete in an oversize jacket once more, physically breaking the spell of conformity when she snaps her Spring Fling Queen crown into pieces. She then joins a group of friends on the school lawn wearing a simple getup: white shirt, dark jeans, big smile. By the end of The Devil Wears Prada, Andy has found not only her true calling as a newspaper journalist but a sartorial middle ground between the over-the-knee Chanel boots (ridiculous) and the bargain-basement sweaters (also ridiculous). The idea in these films is that the soup-eating nerds have learned a thing or two from their foray into conventionality and they’ve come back with souvenirs. This is unlike Legally Blonde, where the transformation is more of a straight line—after all, it’s not as if Elle Woods goes back to being a hyper-litigious sorority sister.

![]()

Cinderella, dirs. Clyde Geronimi, Wilfred Jackson and Hamilton Luske, 1950

![]()

Grease, dir. Randal Kleiser, 1978

The older a film’s vintage, the less the “bounce back” effect of the makeover, meaning less of a harkening to our heroine’s natural traits. Here’s a good litmus test: By the third act, are they wearing something that’s “them” or are they wearing something that has been, in the words of Miranda Priestly (Meryl Streep, channeling a certain formidable fashion editor), decided for them? As with Mean Girls, there’s a pivotal tiara scene in Miss Congeniality. Gracie Hart rips a crown from another contestant’s head and flings it into the air where it promptly explodes. Gracie’s efficacy as an FBI agent is undeniable. However, the film ends with her having been transformed by a coterie of men (cops and pageant underlings), all adhering to the same standard of beauty. In She’s All That, Laney Boggs (the surname equivalent of glasses on a beautiful woman) is able to fend off a potential rapist because she carries an air horn in her purse. Just like a statistic-wielding dork would do. This is one of the moments that have made She’s All That ripe for satirization. (Namely, a 2015 Saturday Night Live sketch and a 2021 script-flipping Netflix vehicle called He’s All That.) She’s All That is Easter Parade, only stripped of charm, depth, style and music. But it is pretty adorable when the two leads slow-dance in the backyard.

The beloved Clueless (1995) also has older storytelling roots. It’s a retelling of Jane Austen’s Emma and revolves around Cher (Alicia Silverstone), a well-intentioned but meddlesome teen in Beverly Hills who decides to spiff-up Tai (Brittany Murphy, the new kid in school), from grungy to 90210-worthy. But Clueless, despite being a popular example of a modern makeover movie (“Cher’s main thrill in life is a makeover,” explains her friend Dionne; “it gives her a sense of control in a world filled with chaos”), comes with an interesting, genre-subverting catch. Murphy’s legendary performance notwithstanding, it’s not her story, not by a long shot. It’s Cher’s story. Cher makes a few attempts at self-improvement (or self-sacrifice, in the form of donating her skis to charity) but is consistently herself. Meanwhile, the transformed Tai’s outcome—romantic and sartorial—is incidental to the plot. The equivalent would be: The Devil Wears Prada, starring Stanley Tucci. What makes Clueless so clever and lasting is the shift in who is performing the makeover. It’s not some guy making a bet; it’s a female friend, in it for the love of the game.

Ultimately, each of these films, no matter their variations, are an accidental compliment from the patriarchy: A woman’s goodness and fundamental appeal are a given, the very baseline of the Unseen. Now these birds just need to learn how to walk and talk and pucker so that people (male people) will have a trail of breadcrumbs that lead to all that profundity. So that they can be partnered just as swans are meant to be partnered. Behold: Emilio Estevez’s face upon seeing Ally Sheedy, a person he has been locked in a room with for an entire day, emerge in...a headband. To be fair, who could see it through all those pesky bangs? Who could have guessed she had shoulders? What man has such superhuman vision?

![<I>Crazy Rich Asians</I>, dir. Jon M. Chu, 2018]() Crazy Rich Asians, dir. Jon M. Chu, 2018

Crazy Rich Asians, dir. Jon M. Chu, 2018![<I>Miss Congeniality</I>, dir. Donald Petrie, 2000]() Miss Congeniality, dir. Donald Petrie, 2000

Miss Congeniality, dir. Donald Petrie, 2000![<I>The Breakfast Club</I>, dir. John Hughes, 1985]() The Breakfast Club, dir. John Hughes, 1985

The Breakfast Club, dir. John Hughes, 1985![<I>She's All That</I>, dir. Robert Iscove, 1999]() She's All That, dir. Robert Iscove, 1999

She's All That, dir. Robert Iscove, 1999![<I>Mean Girls</I>, dir. Mark Waters, 2004]() Mean Girls, dir. Mark Waters, 2004

Mean Girls, dir. Mark Waters, 2004![<I>Clueless</I>, dir. Amy Heckerling, 1995]() Clueless, dir. Amy Heckerling, 1995

Clueless, dir. Amy Heckerling, 1995

“These films promise transformation in three hours or less.”

It’s a strange phenomenon, that a whole genre of plot is aimed at one gender. As if, for all our laudable qualities as women, we are the ones in need of fixing up. The men get a makeover movie on occasion (Hitch, Can’t Buy Me Love, The 40-Year-Old Virgin, Crazy Stupid Love—something about Steve Carell screams out for a head-to-toe landscaping), but these exceptions prove the rule. I’d venture that no straight woman has ever met a straight man she thought could be radically transformed by a haircut. Sure, in our youth, some of us made “pro/con” lists and dreamed of wholesale revision. But I have seen some of these lists and “bad accent” or “dresses poorly” are not on them. It’s more like “hates his mother” and “trouble with monogamy.”

The makeover movie will continue to recycle itself in the same predictable way. Because we want it to. Still, there are signs of variation—even progress. Crazy Rich Asians (2018), for example, is a breath of fresh air for the genre. Rachel Chu’s (Constance Wu) chrysalis moment is about conforming to another culture in the name of family, not impressing a love interest who already loves her back. Nor is it to alter his view of her. It’s about highlighting qualities apparent within her character, not unlocking ones no one has ever seen because she’s wearing some sophisticated cloaking device (a ponytail). Like any lighthearted makeover movie, Crazy Rich Asians involves a glamorous costume change or two (these are movies, after all, not radio plays), but the idea is not that our heroine’s life is a mess—she’s an adorable, affable economics professor. Rather, the idea is that her environment is a mess. It’s the other characters who need to accept how valuable she already is. They’re the ones who need the makeover, not the woman walking confidently in their direction.