The Agony and the Ecstasy

By Will Chancellor

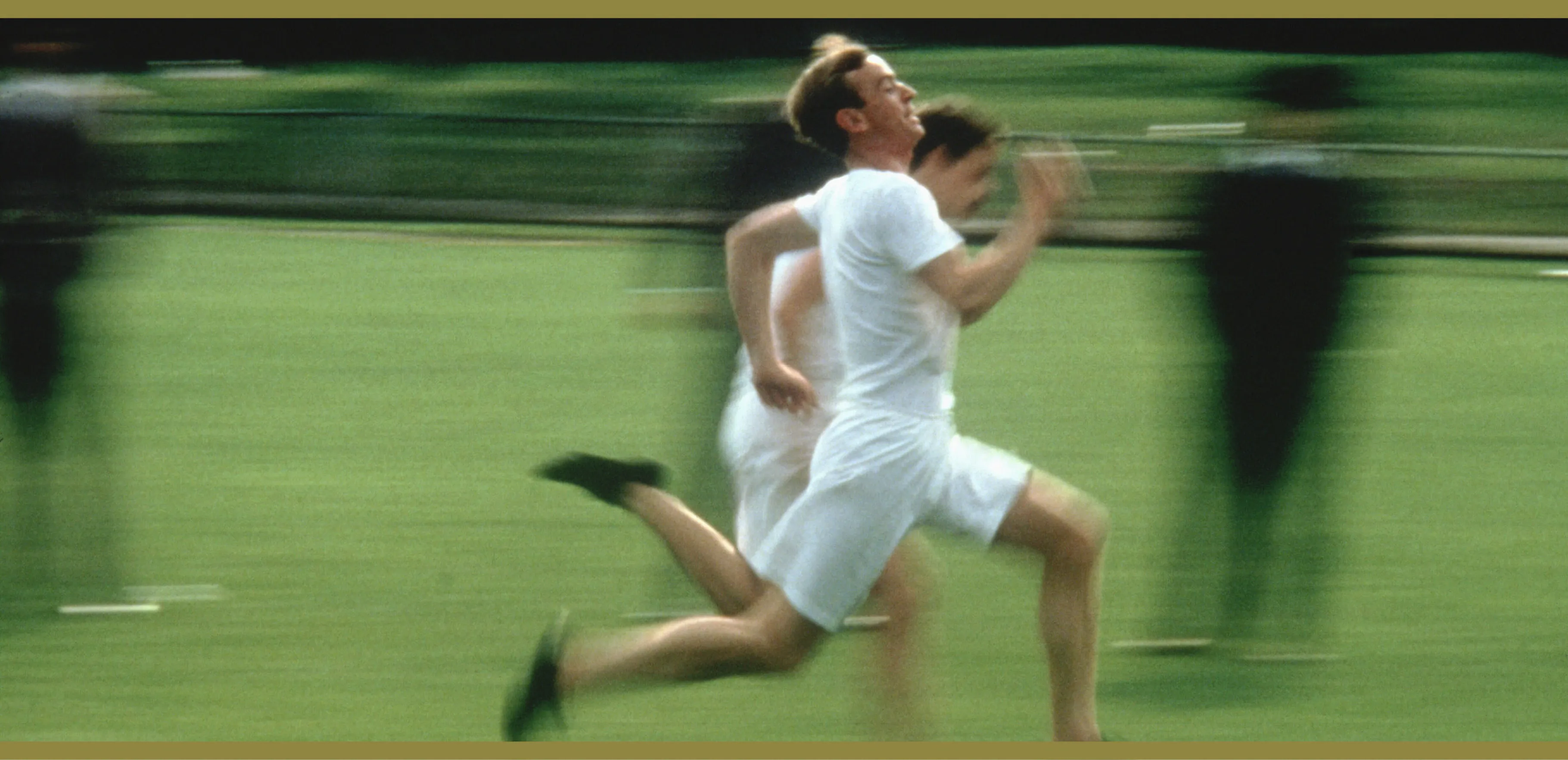

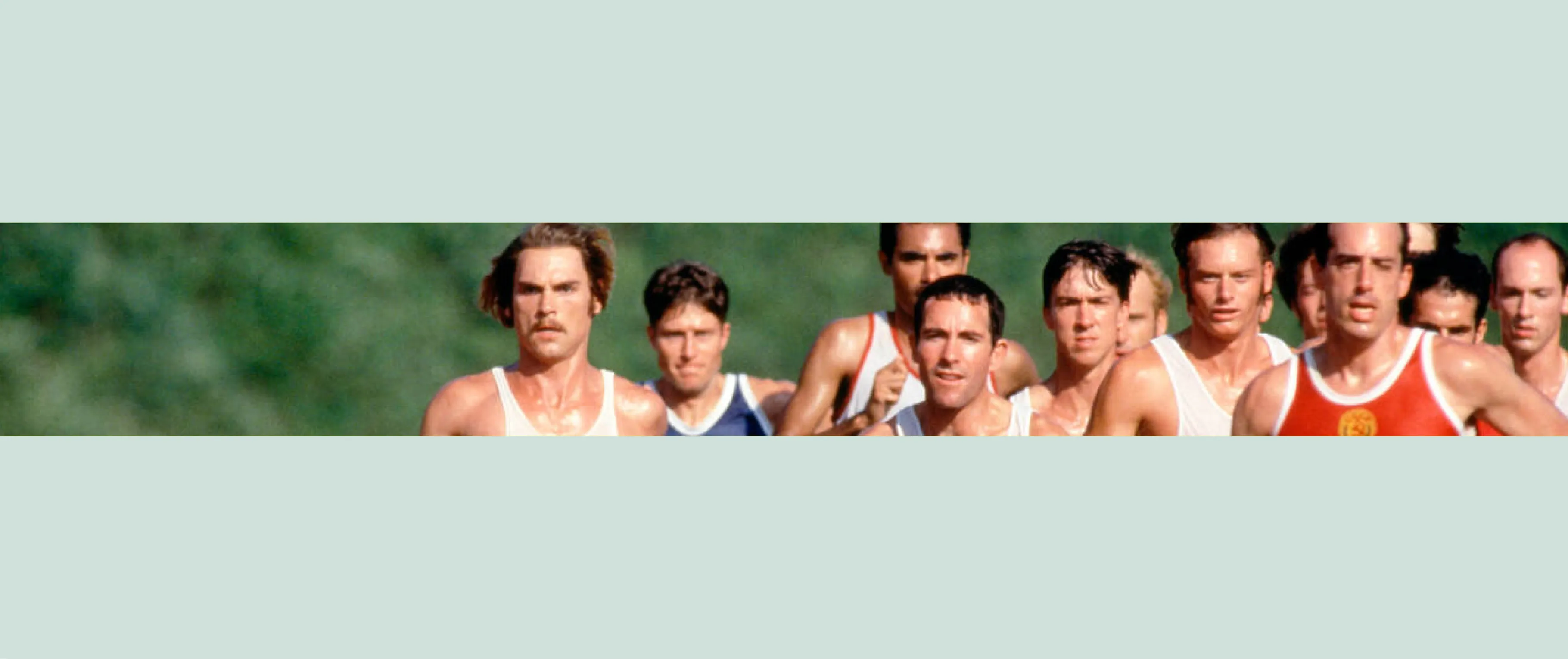

Chariots of Fire, dir. Hugh Hudson, 1981

The Agony and the Ecstasy

Endurance, willpower and faith in three films about Olympic running

By Will Chancellor

August 2, 2024

As the Paris 2024 Olympic Games beams its 45 sporting events around the world, it’s worth considering which films over the years have managed to capture all the majestic, messy, nerve-racking glory of Olympic competition. Most likely, the first film to come to mind is director Hugh Hudson’s 1981 real-life period drama Chariots of Fire. Beyond that, mostly winter-sports films fill the slots, a medley of hockey players (Miracle, The Cutting Edge), figure skaters (I, Tonya) and Jamaican bobsledders (Cool Runnings). The ancient Games were limited to displays of individual prowess, but Hollywood has largely focused its efforts on team sports, which abound in interpersonal drama but rarely offer the nuance of players struggling with motivation and doubt. The exception is running, where directors have managed, with degrees of success, to depict the complex struggle of the individual endurance and willpower of the runner. In doing so, these films convey a lot about how we as a culture perceive sportsmanship.

Chariots of Fire

Apart from the slow-motion running sequence set to a Vangelis score on St. Andrews beach at low tide, sand kicking up the calves and dotting the crisp white polo of each trailing athlete, apart from the unity of the tight pack and a lingering close-up of each runner’s individual expression, what scenes from Chariots of Fire remain in our collective memory? Rewatching it recently, I found the film far stranger than I remembered: mundane for long periods of plot exposition about the class struggles in postwar Britain of a Jewish man and a Scotsman, but brilliant and truly bizarre in situations that would seem most predictable, like how to celebrate a win.

Chariots tells the story of two British runners prospecting for gold at the 1924 Paris Olympics. Eric Liddell (Ian Charleson), is recognizable on that stretch of Scottish beach where they are training by his distinctive running style: chest bowed out, head slung back, eyes firmly on the Lord above. For the Flying Scotsman, a pious Christian, running is an expression of God’s transcendence. “I believe that God made me for a purpose—but He also made me fast,” he decrees. “And when I run, I feel His pleasure.” Liddell’s climactic struggle is not about discovering the meaning of running; it’s one of scheduling. The Olympic Committee slated the 100-meter preliminary heats for a Sunday, the Lord’s day. As a result, Liddell declines to compete. Just when it seems as if the world might be forever deprived of the opportunity to witness a generational talent, a teammate offers up his spot in the 400-meter dash, opening up a window for Liddell, albeit at a less familiar distance. Perhaps because the Lord wills it, Liddell emerges triumphant, bringing gold to England.

“It’s easy to forget in all of the agony and ecstasy of professional sports that they are by definition also a form of play.”

Harold Abrahams (Ben Cross), the other protagonist of Chariots, has an approach to running that contrasts profoundly with Liddell’s. The legacy of Chariots, which I believe has shaped—or at least reinforced—how we conceive running, is that the spiritually driven Liddells are rare, and for everyone else success is only possible through serious struggle. Abrahams’s combative drive is evident in the opening scene. Even on a light beach run with teammates, barefoot and free, Abrahams clenches his fists in determination.

Abrahams is pitted against Liddell for the first time in an open meet in London. They are racing the 100 meters and it’s not even close. Liddell paddles the air and his bowed chest breaches the finish-line ribbon with profound inevitability. In the last meters of the race, Abrahams looks shattered. Interestingly, he will wear this same look of agony when racing for the rest of the film. He’s so far behind Liddell that he’s scarcely in the frame. We see the finish again in slow motion, this time centered on Abrahams. Pause the scene and you’ll think that he might be screaming. His eyes are bolted closed and his mouth is stretched wide. He opens his eyes to see that he’s lost face. Those eyes register rage and disbelief. As he slows, Abrahams’s expression drops into a pit of shame and despair. New lines are cut in Abrahams’s face this day, and this expression proves indelible.

At times it seems as if Abrahams’s characterization bends too stereotypically toward the trope of the long-suffering Jew, but then we remember that the story overlaps with Munich’s Beer Hall Putsch. This context adds electricity to Abrahams’s eloquent description of the maddening frustration of near-constant anti-Semitic microaggression. “It’s an ache, a helplessness, an anger. One feels humiliated. Sometimes I say to myself, ‘Hey, steady on, you’re imagining all this.’ And then I catch that look again. Catch it on the edge of a remark, feel a cold reluctance in a handshake.” His running mirrors his struggle and is the hammer he will bring down on that oppression. When his fiancée asks if he loves running he replies, “I’m more of an addict. It’s a compulsion, a weapon.” After he’s defeated in the 200 meters, Abrahams clings to the 100-meter dash, as his last chance at Olympic gold.

The contrast between Abrahams (agony) and Liddell (ecstasy) is clearest in the moment when each brings home gold—Abrahams in the 100 meters, Liddell in the 400 meters. Liddell’s victory is as one would expect: crushing the competition, bounding forward with a total loss of self, raising hands in triumph, laughing with Sousa-like fanfare as cymbals crash and being hoisted aloft. Abrahams’s race, by contrast, seems out of a horror film. Vangelis scores the scene by oscillating a synthesizer’s high-pitched whine to an eerie OoooOOoooOOoo. Abrahams sees the 100 meters as “10 lonely seconds to justify my whole existence,” but those 10 seconds play out in two minutes and thirty seconds of screen time. Fifty agonizing seconds elapse from the time Abrahams takes his mark until the starter’s gun fires. He races to the soundtrack of muffled applause, crosses the finish line in near silence and clutches his ribs as if he’s been stabbed. The scene replays in slow motion, five shots from the race intercut with the awkward congratulations of his teammates.

Later, in the locker room, a teammate sips champagne and calls out to Abrahams, only to be cut off by a more veteran athlete:

“Shhh. Leave him be.”

“But he won.”

“Exactly. Now, one of these days, Monty, you’re going to win yourself. It’s pretty difficult to swallow.”

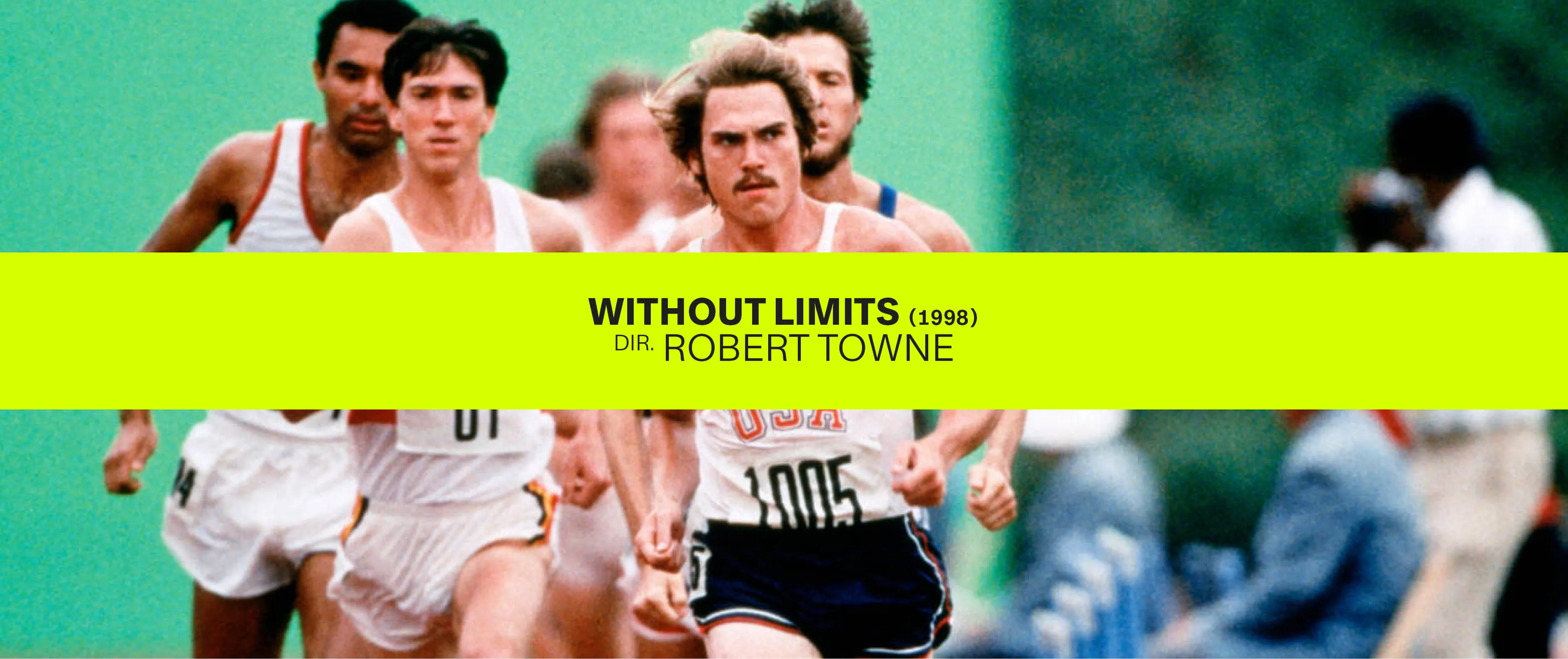

Before watching this film closely, I had never considered that there are two types of victor: the triumphant ecstatic and the athlete suspended underwater, deeper in agony once he achieves his life-orienting goal. Less concerned with victory, director Robert Towne suggests that the true nature of running is a synthesis of agony and ecstasy, a mix of struggle and joy. The famed writer of Chinatown grappled with the psychology of Olympian runners in two of his four directorial features: Personal Best (1982) and Without Limits (1998). The latter provides Towne with the perfect dynamic to investigate the meaning of athletic endeavor by centering on real-life athlete Steve Prefontaine and his relationship with coach Bill Bowerman.

In Towne’s film, Billy Crudup plays Pre from recruited high school runner to former Olympian struggling to reshape his life in the wake of disappointment. Pre is what’s termed a front-runner: He goes full out from the instant the starter fires his gun and doesn’t stop until the tape sashes across his chest 5,000 meters later. Donald Sutherland plays his college coach, Bill Bowerman, who tries with varying degrees of success to mold Prefontaine into a more complete, strategic athlete. Pre deludes himself into thinking he’s a talentless distance runner who wins by will alone: “I can endure more pain than anyone you’ve ever met. That’s why I can beat anyone I’ve ever met.” Bowerman sees through the psychological work-around that’s holding Pre back:

“Your insistence that you have no talent is the ultimate vanity. If you have no talent, you have no limits. It’s all an act of will, right, Pre?…. Be thankful for your limits, Pre. They’re about as limitless as they get in this life.”

Viewed another way, this could be Bowerman’s film. Sutherland’s performance rates as one of his best. There’s the familiar hint of menace, the devious smirk, the clear-eyed understanding, but also an abiding wisdom. Without Limits depicts Bowerman co-founding a little footwear company called Nike by pressing out rubber soles with his kitchen waffle iron and stitching out prototypes based on Prefontaine’s foot shape. He never veers from his ascetic devotion. Bowerman’s total effort to understand the greater significance of all this caloric exertion makes for a round character who sounds completely natural delivering a line like the following to each new crop of college freshmen: “Running, one might say, is basically an absurd pastime upon which to be exhausting ourselves. But if you can find meaning in the kind of running you have to do to stay on this team, chances are you will be able to find meaning in another absurd pastime: life.”

Personal Best, dir. Robert Towne, 1982

At age 21, Steve Prefontaine represented the United States in the 5,000 meters at the Munich Olympics of 1972. Without Limits dramatizes the athletes’ sleepless night as gunmen from Black September execute two Israeli athletes and take another nine members of the delegation hostage. After a failed rescue attempt at the airport, all Israeli hostages were killed, casting a pall over the Games. Bowerman contextualizes the tragedy while also motivating the United States national team. “This killing of Israeli athletes is an act of war. And if there’s one place that war doesn’t belong, it’s here. For 1,200 years, from 776 BC to 393 AD, your fellow Olympians laid down their arms to take part in these games. They understood that there was more honor in outrunning a man than in killing him. I hope the competition will resume. And if it does, you must not think that running or throwing or jumping is frivolous. The Games were once your fellow Olympians’ answer to war. Competition, not conquest. Now they must be your answer.” Prefontaine looks determined in close-up. As viewers, we think gold is all but assured.

The 12-and-a-half lap race begins at an extremely slow pace. Pre is boxed in, denying his natural front-running style. A television commentator dramatizes the psychology: “No athletes study each other like distance runners. So they’ll try to be stoic. All except Steve Prefontaine, who shows it. It’s as if he takes the pain personally and is offended by it.” On its surface, this analysis seems in line with the Abrahams mode of agony running, but Pre’s expression is different. He looks as if he could be running in a meadow until he decides to make his break and carefully sidesteps without tripping over a competitor’s legs. Once he has the lead, the commentators speculate that no one can undertake a “mile-long drive to break the best runners in the world.” Prefontaine, suffering stoically rather than wearing his pain, falls behind and then regains the lead, then falls behind, never breaking a sweat. Prefontaine looks to his side going into the final turn of the final lap and crosses…fourth.

Devastated at the realization that his absolute best came up short, Pre begins drinking and retreats to his trailer in the woods. It takes a great coach to bring him back and give him hope. “I haven’t noticed you working out all that much,” says Bowerman during a visit. “You know the greatest race I ever saw you run? Munich…. You couldn’t have done more than you did.… At your level of competition, anyone can win on any given day, and not necessarily the best man.”

Without Limits, dir. Robert Towne, 1998

Ultimately Pre comes around to Bowerman’s way of thinking, that elite running is not an Abrahams-esque pursuit of enduring pain and having the most grit. Nor is it a Liddell-esque suspension of real limitations. Crudup portrays Pre as finally running with full cognizance of his own talents in preparation for the 1976 Olympics. The joy has returned to his stride. Pre is now close to becoming a secular Liddell and a self-aware Abrahams, which adds poignancy to a tragic ending—the very day he won a 5,000-meter race at his home track at the University of Oregon, he flipped his car driving home from a party and died at 24. In his eulogy, Bill Bowerman states: “Pre...finally got it through my head that the real purpose of running isn’t to win a race. It’s to test the limits of the human heart. And that he did. Nobody did it more often. Nobody did it better.”

It’s easy to forget in all of the agony and ecstasy of professional sports that they are by definition also a form of play. Nothing is so demonstratively serious as an athlete competing on a world stage, which can overshadow the fact that sport—and particularly Olympic sport—is a celebration of the body. In this light, Towne’s first effort on competitive running, Personal Best, exists as a winking counterpoint to the seriousness of the Abrahams and Liddells of the world. This meandering, often bonkers, occasionally prurient film (read: two nude sauna scenes) attempts to examine the fundamental purpose of sports when there is no ultimate reward. Specifically, it does so by removing the motivating factor of any chance of Olympic gold.

Personal Best follows the tribulations of would-be Olympic pentathletes Chris Cahill (Mariel Hemingway) and Tory Skinner (played by actual Olympic hurdler Patrice Donnelly) training for a Games that, for them, never will be. The United States boycotted the Moscow Games of 1980, destroying the hopes of hundreds of athletes who had dedicated their lives to this particular flavor of glory. Even for those who did get to compete in previous Olympics Games, victory proves Pyrrhic. Cahill’s boyfriend, a two-time gold medalist, describes the hollow heart of an Olympic dream: “I sort of walked out there and they hung it around my neck and played the national anthem. And I do remember thinking, ‘This is it?’ Twenty thousand meters a day since I was 10 and this is it?” Abrahams’s teammate appears to have been right: Winning is hard to swallow.