The Walking Cure

By Katya Apekina

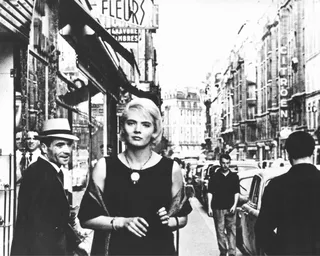

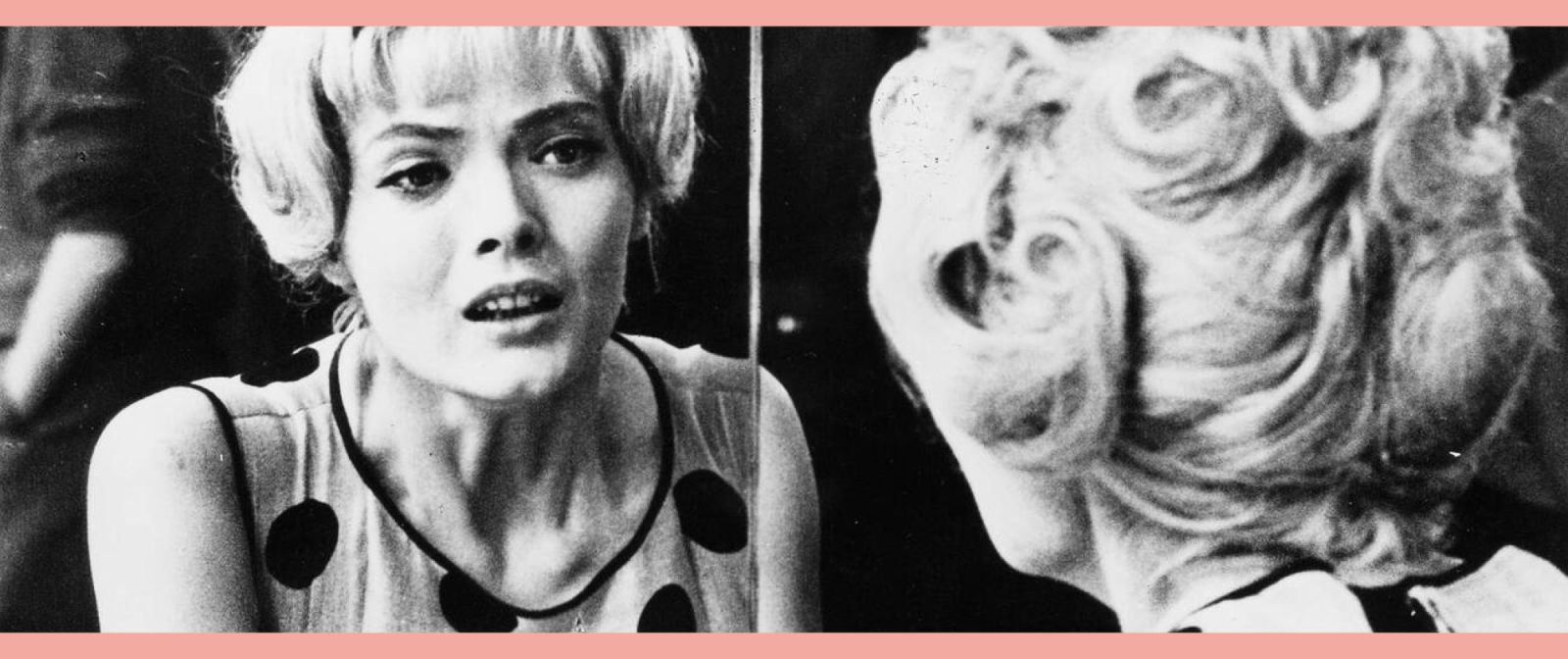

Cléo from 5 to 7, dir. Agnès Varda, 1962

The Walking Cure

An early Agnès Varda film proposes movement as medicine for crisis

By Katya Apekina

November 15, 2024

Agnès Varda’s Cléo from 5 to 7 opens with the musical talent Cléo bursting into tears after a bad tarot reading. She’s awaiting medical test results and is sure this means she has cancer, and that it’s terminal.

AUTHOR READS

Street scenes in Cléo from 5 to 7

After the reading, the film, which begins in vivid color, leaches into black and white for the duration as Cléo confronts her mortality. She cries to her assistant in a coffee shop, spiraling with anxiety about her own tragedy. Lovers at the next table are arguing about sleeping arrangements. When Cléo overhears them she’s knocked from the circuit of her grief. Her attention widens; if only for a moment, she can see past herself. The manager comps her coffee, she buys herself a silly little hat—maybe things aren’t so bad? But when Cléo returns to her apartment, she’s trapped with her despair. Wearing a feathered housecoat, she perches like a caged songbird on a swing that hangs from the ceiling. “Everyone spoils me, but no one loves me,” the pet says petulantly to her songwriting team and assistant, who are all on her payroll and trying to distract her from what they’re sure is hypochondria. To get away from them, and herself, Cléo storms out and goes for a walk in the city.

This movie captures like nothing else I’ve seen the transcendence of going on city walks. I too am often finding myself in a vortex of my own fears. Sitting feels impossible and walking is the only cure. At times in my life when grief gave me tunnel vision, moving among strangers, overhearing snippets from their conversation, noticing a bird or a cloud or somebody’s crumpled up biology notes or a spray-painted penis or a halo around the moon—this is the detritus that brought me back to myself. It’s through walking around Paris that life seeps in for Cléo: chance encounters, street performers, possibly even love—all set against the excitement, oddness and largeness of the city.

“The streets will titillate and repulse, distract you from your fear of death and then remind you of it.”

In Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Rebecca Solnit writes, “Everything—houses, churches, bridges, walls—is the same sandy gray so that the city seems like a single construction of inconceivable complexity, a sort of coral reef of high culture. All this makes Paris seem porous, as though private thought and public acts were not so separate here as elsewhere, with walkers flowing in and out of reveries and revolutions.”

This strollable Paris, with its iconic boulevards, was only about a century old when Cléo was walking it—the whole city had been rebuilt, brought out of medieval times of narrow, unsanitary streets by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, who restructured the city around wide boulevards and pedestrian-friendly arcades. There were gas streetlights, mosaics and marble, café tables that spilled out into the street. The divide between interior and exterior space was no longer clearly defined. It’s in Paris that strolling emerged as a national pastime. There was even a French word for it, the flâneur—an urban walker, loiterer, window-shopper, someone eccentric enough to walk a turtle on a leash or at least a lobster. “The crowd is his domain, just as the air is the bird’s and the water that of the fish,” wrote Baudelaire.

Cléo stops at a shop window to stare at her reflection, her own self-described “doll face,” but she is pulled out of her self-obsession by the sight of a man swallowing and then vomiting up frogs: fascinating and revolting. She later witnesses someone with an arrow sticking out of his bicep, a recently shot body surrounded by a crowd of onlookers. The streets will titillate and repulse, distract you from your fear of death and then remind you of it.

A scene from Cléo from 5 to 7

I remember my very first night walk. I was at a sleepover in sixth grade, and a gaggle of us snuck out and roamed the streets of suburban Massachusetts. We walked past people’s living rooms, awash in the blue glow of television sets, and past a lit bedroom with its blinds open. Though we didn’t actually see anything scandalous, the experience ignited our imaginations. The things we almost saw! Out in the world, anything was possible.

At one point, Cléo ducks into a café and puts her own song on the jukebox, then wanders through the tables, hungrily watching for people’s reactions. A couple complains about the racket. It’s strange making art and putting it out into the world, not really knowing how it lands on the other side. It’s not often a creator gets to see an honest reaction, and it’s a common writer’s fantasy too to see someone in the wild reading your book. This happened once to a friend of mine on the subway—he coyly asked a woman reading his novel what she thought, and she had not been sufficiently effusive. Cléo is disappointed too—the anonymity does not give her what she’d hoped. Accustomed to the sycophants on her payroll, she is bemused to confront indifference.

Cléo is the one among her friends who has “made it,” but what good is fame and glory if you’re dying? She visits a friend ending her shift as a nude model for a sculpture class—a peer whose career as a dancer has not taken off. The friend is jealous of Cléo’s success, of her wealth and status, but she can also see that fame has not given Cléo the things that make a life. After all, Cléo is wandering around Paris alone. She is generous with her friend, literally giving her the hat off her head, the silly little hat she bought earlier in the evening. Her friend takes it greedily and is gone.

From left: pedestrian life in New York, Paris and Los Angeles

Sometimes strangers save you in a way your friends can’t. Fewer resentments. A fresh start. In a park at dusk as the songs of evening birds erupt, Cléo meets a man—a stranger—on a bridge. It’s a chance meeting, and she’s too distracted to have her guard up. It’s the solstice, the longest day of the year. “All men wait for women. Then they speak to them. I don’t usually reply, but today I forgot,” she tells him. He explains that he’s on military leave, it’s his last night before he’s sent to Algeria. Somehow, with this stranger, she is able to speak more honestly than with anyone else. “I’m afraid of everything: birds, storms, elevators, needles and now this great fear of death,” she tells him.

When my daughter was little and in the hospital, I remember taking a walk. I’d been cooped up with my child in the hospital room for days. She was getting better, and I took a break. I could not stop grinning. I was so happy to be outside in the sunshine and not in the overly air-conditioned hospital room, with its antiseptic smells, endless beeping and plastic trays piled with fruit cups. I ran into my mechanic. “How are things? How’s your girl?” he asked me, as he always did whenever I saw him. I couldn’t stop smiling, even as I told him that she was in the hospital. I could tell he was taken aback, but I kept walking. I couldn’t explain to him how ecstatic I felt. Just like when I used to live in New York, I would go on walks and weep openly. My face always seemed to be wet, and if I saw someone I knew, I’d cross the street. To emote among strangers out in the world, to not feel like you need to hide or explain yourself to them!

“It’s through walking around Paris that life seeps in for Cléo: chance encounters, street performers, possibly even love.”

I’ve met strangers on walks, too. I met a man on a long walk in New Orleans and he became my husband. We were introduced to each other after a parade, knee deep in trash, under a statue of General Lee that has since been removed. We walked the parade path, on the cobbled streets, past musicians and drunks and kids with tacks on their shoes tap dancing for money. On our first trip together, I remember walking past a man eating a light bulb in Pittsburgh, and deaf people signing to each other, and an old lady clutching her pocketbook. We fought and made up and the world continued around us. Now we live in L.A.—a place where people hike and drive, but where walking is often unpleasant because almost nobody does it. Still, I would put our daughter in a stroller at night so I could go on long walks with her, free to wander around and look at things, and not feel stuck and alone at home, removed from chance and humanity.

The soldier Cléo meets in the park convinces her to go with him to the hospital to get her test results. The hospital, much like the place where my daughter stayed during her illness, is beautiful. The manicured gardens and benches on the grounds give it the appearance of a palace. They try to track down the doctor but give up, and then catch him driving past in a convertible. The doctor assures her that she has something, but it’s curable. The heaviness she has been running from this whole movie zooms away with his car. Fear can sometimes feel like a mysterious external force, not something internally generated. “I think I’m happy,” Cléo tells the stranger. The two of them stroll side by side in the same frame. The camera stays tight on their faces. They don’t kiss. Maybe they never will. The walk worked.

From left: La Place de la République in Paris; Paris Street; Rainy Day by Gustave Caillebotte, 1877; an aerial view of Paris from the Arc de Triomphe