What's Your Damage?

By Sloane Crosley

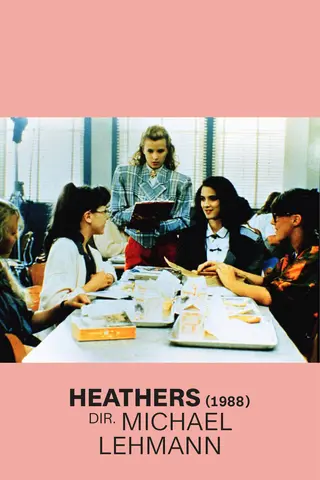

Heathers, dir. Michael Lehmann, 1988

What’s Your Damage?

Sloane Crosley

The queen bee of high school toxic-female-friendship films works

because of—and not despite—its uncomfortable cruelty

November 28, 2023

From left: Winona Ryder and Christian Slater in Heathers; power dynamics on display in the high school cafeteria

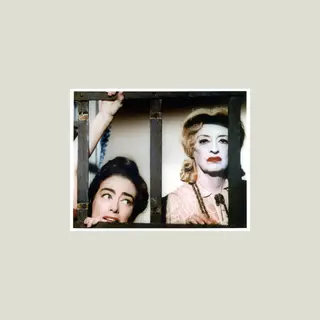

One night in 1989, I couldn’t sleep. So I snuck out of bed, went into the living room and turned on the television at a low volume. I treated my 11-year-old brain to a double feature. The first was a made-for-TV movie called I Know My First Name Is Steven, based on a true story about a little boy who was abducted and raised by his abuser, only to remember his real identity years later. The second was the 1962 classic What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, starring Bette Davis and Joan Crawford. For the uninitiated, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? is a psychological horror film about two sisters, both former Hollywood child stars. One (Crawford) is wheelchair-bound because of a car accident that she’s allowed her little sister (Davis) to believe is her fault. It’s one of the most iconic female-rivalry films of all time (neck and strangled-neck with the 1950 Joseph Mankiewicz film All About Eve, also starring Davis). In What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, you’ve got your murder, your kidnapping, your starvation, your raging jealousy, your disturbing amount of clown makeup. Watched in sequence, that visually traumatic film, and the otherwise unrelated I Know My First Name Is Steven, bled together in my preadolescent memory. Which could explain why I spent the next two decades assuring anyone who would listen that What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? was based on a true story. Even now that I’ve been corrected, I ask: Is it any wonder? When I survey our onscreen portrayals of toxic female friendships…is it any wonder I thought it was real?

From left: What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, dir. Robert Aldrich, 1962; All About Eve, dir. Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1950

Modern cinema is littered with satire about the knotty nature of young women’s bonds, especially the age when young-adult life narrows to an enclosed fiefdom under a dome of hormones and near-feudal rules about competition, gender, betrayal, justice, dress codes and class. But there is one constant. Even within the confines of our more upbeat, reassuring lady-buddy flicks (Clueless, Romy and Michele’s High School Reunion, Bridesmaids, Lady Bird, Booksmart), there are always the mean girls. From the performatively perfect to the downright cruel, these vapid vessels get boiled down to a plot point the moment our heroines realize they don’t actually have to impress them. Or even associate with them. Here, mean girls prove to be stepping stones, not stumbling blocks, on the road to self-actualization. But they’re never not there.

This is not because of some grand scheme on the part of the patriarchy to portray female friendship as a civil war, to divide and conquer (though surely the patriarchy can’t help but attempt to manipulate women’s priorities). It’s because…well, have you attended high school in the past century? This is what being surrounded by kids your own age feels like. When things go wrong, it becomes challenging to see a viable escape hatch or a future path. Rejection from the class “cool girl,” or betrayal on the part of one’s best friend in favor of said cool girl, is more insidious than any romantic heartbreak. Because it is not easily dismissed as an absence of chemistry. Nor does it have a library of torch songs and poems to use as a balm. Rejection or mockery by a fellow girl, one whose opinion you value, is digested as a referendum on who you are and how others will see you, probably for the rest of your natural life.

But 1989 was not merely the year an 11-year-old suburban girl snuck out of her bed to watch bad television. It was the year that saw the U.S. release of the ultimate portrayal of female friendship gone awry, the watershed film for the vicious girl group: Heathers. It is difficult to overstate the importance of Heathers on the American clique plot (arguably the 20th century’s answer to the marriage plot), on the very idea of a dark comedy and on the level of complexity—the cruelty, the elaborate social politics, the pressing concerns—it granted to an entire age-group.

From left: Cruel Intentions, dir. Roger Kumble, 1999; Dangerous Liaisons, dir. Stephen Frears, 1988

First-time director Michael Lehmann helmed the twisted story of four popular and heavily scrunchied juniors ruling the roost at an Ohio high school, three of whom are named Heather. “The Heathers” and their ilk start turning up dead once mysterious, gravel-voiced anarchist-psychopath J.D. (Christian Slater) shows up at school and befriends the fourth girl in the clique, the aptly named brunette Veronica (Winona Ryder). He taps into her moral quandaries about ingratiating herself with the Heathers in the first place. He, like, totally gets her. J.D. is Veronica’s love interest, sure, but he came to her heart second: Her first love is the three Heathers (Veronica’s earnest efforts to become part of the clique are alluded to early in the film, but by the time we meet her the Heathers’ cruel antics have begun to make her squirm). Similar to its predecessors, like Brian De Palma’s Carrie (1976) and even the aforementioned Baby Jane, the magic of Heathers is to be found in two places. First, the fact that while men are used as tools for humiliation, our heroine’s true highs and lows hinge on her female friends. Second, in the outsize violence of the entire endeavor, which gives a visceral, murderous take on the very idea of the “toxic female friendship.”

Heathers looks high-school politics square in the eye and refuses to have a measured or even embarrassed response to the most humiliating period of our lives. It shows no weakness, takes no prisoners. And it confirms our worst suspicions about teenage girls—a rising tide does not lift all boats, the spotlight was made for one, it’s every Heather for herself—and delights in the results. The film features suicides (real, staged, attempted), explosions, date rape, shootings, funerals and blood. So much blood. There’s even a death-by-Drano. In one of the film’s more iconic scenes, the “head Heather,” the blonde antagonist Heather Chandler (the late Kim Walker) is killed off when she ingests an alleged hangover cure whose active ingredient is drain cleaner. As she chokes, gripping her neck and smashing through a glass coffee table, she utters her last words, “corn nuts,” a reference to the previous night’s snack which she made Veronica purchase for her en route to a frat party. The entire scene is, in the film’s sarcastic parlance, beautiful. It’s visually beautiful as well. Heather’s kitchen is dotted with bright red appliances (her signature color). Her dream ’80s bedroom is massive and strewn with pink silk accents, suggestions of a recently departed girlhood. Then there’s that red scrunchie in Heather’s hair, which she removes in a “hold my beer” fashion before boldly drinking the killer cocktail, thus symbolically dethroning herself moments before her death.

Most of Heathers is like this, stunning and violent, campy and cruel. The film is a revolt that capped off a decade of sentimental heterosexual high school homecoming movies, looking back over its (padded) shoulder as it opened the door to the grungier ’90s and asking: What if all those emo John Hughes characters had just set the gym on fire instead?

From left: Carrie, dir. Brian De Palma, 1976; Jennifer's Body, dir. Karyn Kusama, 2009

And yet, for all the wonderful groundwork it laid (yes, teenagers are whole people with politics and pain, whose actions have real consequences), the violence in Heathers is so ubiquitous and self-glamorizing as to be, in wider 2023 eyes, uncomfortable. The film leaves a barrage of unintentionally cringy jokes about suicide, rape and hate crimes in its wake, mixed in with all the more wittily intentional ones. Friends of mine who grew up in Ohio in the ’80s and ’90s found the story to be unflinching in its accuracy (yes, the homophobia really was that open and the threats that direct). But watching the movie now can be disturbing in unexpected ways. J.D.’s homicidal tendencies are all well and good (one roots for this maniacal loner James Dean–type as a speaker of truth) until he whips out a gun in the cafeteria and plots to blow up the school. The film predates the Columbine High School massacre by almost exactly a decade. The language and concern around student violence has, to put it mildly, shifted. Even the black trench coat worn by J.D. has become coded for the worse.

Then there are the references to teenage suicide itself, which are unquestionably heartless. Heathers is such a sacred monster to a whole generation that you might read that previous sentence, recall the hilarious “My son’s a homosexual and I love him. I love my dead gay son!” delivered by a grieving father over his son’s open casket, and think I’m trying to take away a beloved toy. I assure you, I’m not. Upon rewatching it, I lost count of the suicide references in Heathers, of the callous way they are handled even within a movie where callousness about life and death is the point. The subject of date rape hardly fares much better. In a nighttime cow-tipping scene involving two characters arguing in the foreground, we barely notice the date rape of one Heather (Lisanne Falk) on a field in the blurry background. This is in addition to approximately three attempted rapes in the film, moments when perverse satire veers into unwitting documentary.

Even through this haze of contemporary triggers, though, there are moments where cooler heads prevail. Moments of real softness that make it possible to love the perverse joyride that is Heathers sans guilt, to, despite it all, relate to the characters. In the midst of mourning her dumb jock boyfriend, Heather McNamara (the most guileless of the three Heathers) calls a local radio show and laments that she was “supposed to be captain of the cheerleading team” and her “parents are divorced and stuff.” The next day, teased by those who heard her confession (“Heather told everyone about Heather”), she absconds to the girls bathroom with a bottle of pills and attempts to shove them all into her mouth at once, like a crumpled up note. Veronica finds her in time and admonishes her for throwing her life a way to “become a statistic in US-fucking-A Today.” As the two sit slumped against the tile, Veronica holds her hand and comforts her: “If you were happy every day of your life, you wouldn’t be a human being, you’d be a game show host.” Heather, in turn, leans on Veronica’s shoulder. Heathers is not exactly brimming with legible lessons about female friendship (aside from Try not to torture other people so much), but this moment of kindness is rare glimpse of selfless connection between two popular girls.

“The film is a revolt that capped off a decade of

sentimental heterosexual high school homecoming movies,

looking back over its (padded) shoulder as it opened the door to the grungier ’90s...”

Countless subsequent teen movies (and teen horror comedies) owe Heathers a heavy debt, specifically those of the late ’90s. There are cult/occult favorites like 1996’s The Craft, in which a new girl falls in with a group that practices witchcraft, conspiring to make a fellow student’s hair fall out. And while 1999’s Cruel Intentions can trace its lineage back a tad farther than Heathers (the movie is a beat-for-beat modernization of Stephen Frears’s Dangerous Liaisons (1988), which is based on Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’s 1782 French novel by the same name), try watching Sarah Michelle Gellar’s calculating cruelty and delusional conviction that she’s loved when she’s loathed without thinking of its foremother.

Daniel Waters was Heathers’ screenwriter, partially modeling its characters on the sadistic experiences of his sister and her friends while attending high school in the Midwest. It’s something of an anomaly from a gender perspective. Diablo Cody wrote and Karyn Kusama directed 2009’s Jennifer’s Body (in which a beautiful, confident high school girl becomes a demon, thus putting a damper on her relationship with her best friend). Karen Walton wrote 2000’s Ginger Snaps (in which a beautiful, confident high school girl becomes a werewolf, thus putting a damper on her relationship with her sister). But perhaps one does not have to be a woman to grow up viewing the popular girls as mythical creatures, be scarred for life, become a screenwriter and turn them into actual monsters. Notably, no one in Heathers is a vampire or a zombie. But almost everyone is evil at worst and desensitized at best. Even the film’s most obvious heir apparent, the 2004 hit Mean Girls, explicitly compares the high school social hierarchy to wild animals.

From left: Ginger Snaps, dir. John Fawcett, 2000; Mean Girls, dir. Mark Waters, 2004

The scene in Mean Girls in which Karen and Gretchen (Amanda Seyfried and Lacey Chabert) redirect allegiance to Cady Heron (Lindsay Lohan) while queen bee Regina George (Rachel McAdams) is in the hospital would not exist without Heathers, which hit upon the idea of the need for a teenage despot, even after the other members of the group have been set free. After Veronica and J.D. do away with Heather Chandler, Heather Duke (Shannen Doherty’s role in the film is a quiet revelation) clamors to take her place. “Yes, dear diary,” scrawls Veronica as she speaks in voice-over, “I’ve cut off Heather Chandler’s head, and Heather Duke’s head has sprouted back in its place like some mythological thing my eighth-grade boyfriend would have known about.” If, for some reason, you’ve been searching for proof that Doherty could have just as easily played Jennie Garth’s character on Beverly Hills, 90210, look no further.

Heathers served as jet fuel for the careers of Ryder, Slater and Doherty. But plotlines aside, perhaps the most lasting tribute to teenage-girl toxicity in Heathers, the one that has already stood the test of time, is the host of zingers coming from just about every character. They’re great: “Fuck me gently with a chain saw.” “Color me stoked.” “Lick it up, baby. Lick. It. Up.” “Grow up, Heather, bulimia’s so ’87.” And all those marvelous rhetorical questions! “Veronica, why are you pulling my dick?” “Why do you have to be such a mega-bitch?” “Did you have a brain tumor for breakfast?” “What is your damage?” There is something eternal about delivering a verbal swift kick, preferably vivid, preferably in front of one’s peers. Is this a habit to be emulated in real life? Probably not. Not in today’s era of the Instagram caption and the TikTok and Snapchat rant, when there are more than enough creative routes for teenage girls to bully and gang up on one another.

But the name-calling and verbal pyrotechnics in Heathers is a valve in the same way the violence is a valve. It’s meant to show us all how bad things could get and how ludicrous and worthless it seems when we get there. If there’s a deeper “lesson” in Heathers, it’s a bittersweet one. The film ends with Veronica sauntering down the hallway with one of the unpopular girls, slowly rebuilding her burned bridges. The unpopular girls are not saints merely because the popular ones are sinners; we just don’t know them as well. This was never their show. But it’s a nice idea that something pure and good can be salvaged from the wreckage of adolescent life. It reminds me of the last scene in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? Damage already done, Baby Jane turns to her sister and asks: “You mean, all this time we could have been friends?”